Red Vulns Rising: Examining Chinese National Vulnerability Databases

Tags:

Key points

- There is a whole world of vulnerabilities beyond CVE. China maintains two different vulnerability databases, CNVD and CNNVD, which we examine here.

- China has stricter controls on what vulnerabilities are published and what information is published with them.

- Publication of vulnerabilities in the Chinese databases largely mirrors publication in CVE, occasionally the data has some hygiene and consistency challenges.

- A small number of vulnerabilities (~1.4k) are published in Chinese vulnerability databases prior to when the vulnerability is made public, often by as much as several months.

- Some vulnerabilities in Chinese databases appear to not have been published at all by CVE. Recent Chinese policy changes have changed the publication cadence of these vulnerabilities however.

Introduction

As we stare into the unknowable future that is 2026, it’s useful to look back and examine events of the previous year simply because the trajectory of the future is bent by the arc of the past. Given that my remit is the realm of cybersecurity, and I seem to have focused on the niche of vulnerabilities over the last few trips around the sun, let’s see what the recent events in the realm of vulnerability databases can tell us about what we can expect in the coming year.

For those unfamiliar with the troubles I’ve mentioned, here are two main events that continue to weigh heavily on those of us who rely on vulnerability data.

- In February of 2024, the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) National Vulnerability Database (NVD) experienced a degradation in their yeoman’s work of analyzing every vulnerability published by MITRE’s CVE list. This included assigning, CVSS scores, CWEs, CPEs, to everything published CVE. Since this slowdown, they have reprioritized on more recent vulnerabilities (post 2018) but acknowledge that the backlog continues to grow.

- Shortly after the VulnCon 2025, which included a panel entitled “US CISA’s North Star Vision for the CVE Program” that focused on efforts to improve the coverage and quality of CVEs by their publishing CNAs, news broke that the DHS contract that funds the CVE program had not been renewed and was in danger of lapsing. After a fair bit of panic, including some efforts to essentially fork the cataloguing of CVEs in various ways, the funding crisis was resolved and operations continued uninterrupted.

Concern about the events above is warranted. When institutions have worked reliably for more than a quarter of a century, they tend to become the foundations for the tools that get used every day, both by practitioners in the trenches and by data dabblers like myself. Beyond their overtly technical use, MITRE and NIST are positioned as the de-facto arbiters of truth when it comes to vulnerabilities.

A number of government-controlled vulnerability databases exist outside the United States. A short (and likely incomplete) list includes:

- Japanese Vulnerability Notes (JVN), in both English and Japanese, with substantial differences between the two. Moreover, JVN also maintains JVN iPedia, which is focused on vulnerabilities specific to Japanese products, both in English and Japanese.

- The Russian Federation maintains the Data Security Threats Database, which is their own structured curated list of vulnerabilities. We won’t link here directly because there is currently no SSL chain of trust for most folks to access that particular database, but I am sure the more technical among readers will have no problem finding it.

- The European Union Vulnerability Database (EUVD) is a relative newcomer and is still evolving. Up until recently it largely mirrored the CVE list, providing their own analysis and data formats at times. In particular they are producing information on affected products in their own format independent of CPE, which includes uuid style identifiers for software vendors and product versions.

- This is not the only effort based in the EU. The Vulnerability and Attack Repository for IoT (VARioT) is an EU funded database focused on IoT vulnerabilities, an area we at Bitsight have been particularly active in.

- Less of a database and more of aggregation and standards process (though they do make data available!) is the good folks at CIRCL.lu building and maintaining vulnerability-lookup, aggregating vulnerability identifiers and information from a wide variety of sources.

This list is obviously not exhaustive, and it doesn’t include non-governmental efforts like the Open Source Vulnerabilities. But there is one country we have yet to mention that does have vulnerability cataloguing efforts: China. China, not wanting to fall behind on strategic vulnerability database reserves, maintains two vulnerability databases:

- China National Vulnerability Database of Information Security (CNNVD), which is run by the China Information Security Evaluation Center (CNITSEC) and is overseen by the Ministry of State Security. This database is built to feed China’s offensive capabilities, and when vulnerabilities are disclosed by other parties they are made public by the CNNVD.

- Chinese National Vulnerability Database (CNVD), which is controlled by CNCERT, China’s own Computer Emergency Readiness Team. This database has a more traditional purpose of cataloguing and warning defenders when new vulnerabilities are published.

The databases are separate and contain different identifiers for vulnerabilities and different sets of information. The Chinese Communist Party has put forward strict guidelines and structures for what vulnerabilities are published and how. Most notable among these was a major policy change that was introduced in July of 2021: “Regulation on the Management of Network Product Security Vulnerabilities(RMSV)." This wide ranging policy made many changes to China’s software vulnerability ecosystem; here are a few particularly interesting points:

- Requires sharing of vulnerability information with Ministry of Industry and Information Technology

- Must do so within 48 hours of discovery

- Prohibits sharing of details before a patch is available

- Prohibits sharing PoC or exploits

- Prohibits exaggerating severity

The above are seemingly antithetical to the near anarchic history and current state of Western vulnerability disclosure practices in which the researcher who discovers a vulnerability has a degree of primacy in what they release and how. Western researchers are asked, rather than told, to follow generally accepted Coordinated Vulnerability Disclosure practices. But there are no regulations that govern when someone can find a vulnerability, and, if they so choose, they can just post the details anywhere they please.

The details of the RMSV are fascinating but beyond the scope of what I’d like to cover in this piece; others have covered it in more depth and, honestly, it’s beyond my area of expertise. What I am more interested in, as ever, is what insights can be gleaned from the data in each of these repositories. Given its more prescriptive requirements and government connection, does China's vulnerability database include additional information that might not be collected under Western disclosure systems?

Accessing CNVD and CNNVD

Both CNNVD and CNVD require account creation, email verification, and logins to access data. However, account creation and access seems to be automated and can be achieved quickly.

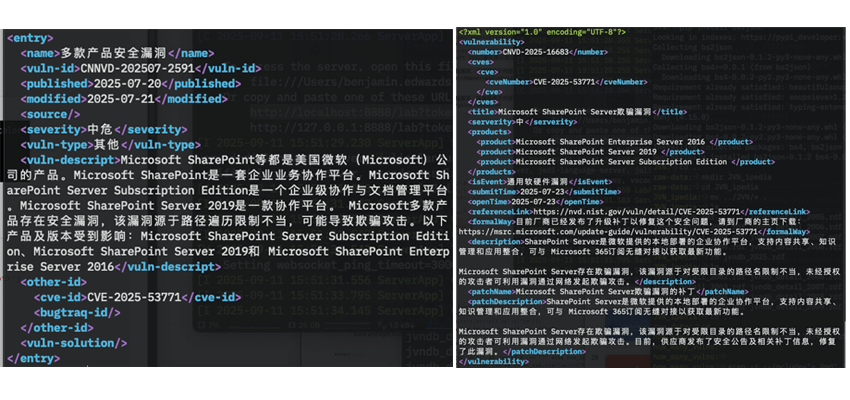

Navigating the sites is a challenge for non-Chinese speakers, but with judicious use of automated translation software, it’s possible to download aggregated collections of vulnerabilities (yearly for CNNVD and weekly for CNVD). There is no easily automatable way to access this data, however. All requests require user interaction and files are generated server-side on demand, meaning that collecting data requires individually clicking on each file to download them1. Once downloaded, the files contain data on vulnerabilities formatted in XML (example entries in Figure 2).

Analyzing CNNVD and CNVD data

While XML is not my preferred document based data format, it can be parsed like any other. However, errors in the entries in both databases mean that simply asking your favorite XML engine to parse the data is not sufficient and somewhat more heroic efforts are needed to extract all valid entries in each. Though, once we do so we are left with two databases that have grown substantially since they were first established.

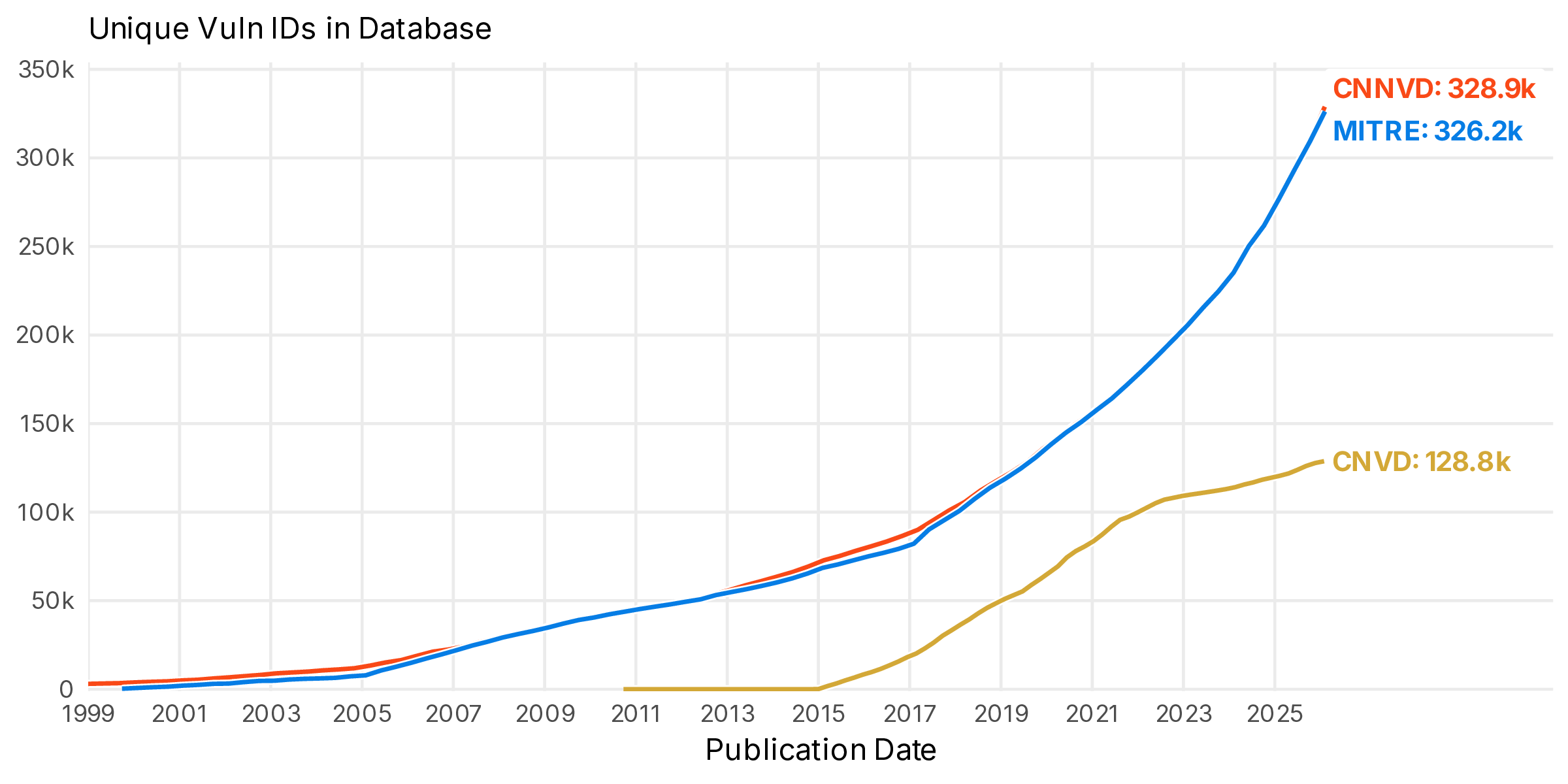

Figure 3 Growth of CNVD and CNNVD from earliest publication date. MITRE CVE list for comparison. Note this contains all public CVEs in the MITRE list including those marked as REJECTED2.

The aligned growth with MITRE’s CVE list is not a coincidence. CNNVD seems to mirror nearly all CVEs. Astute observers will see that in fact both CNVD and CNNVD have fields in their respective schemas for CVE Identifiers. They do not, however, cross-reference each other.

Breaking down severity or “serverity[sic]”

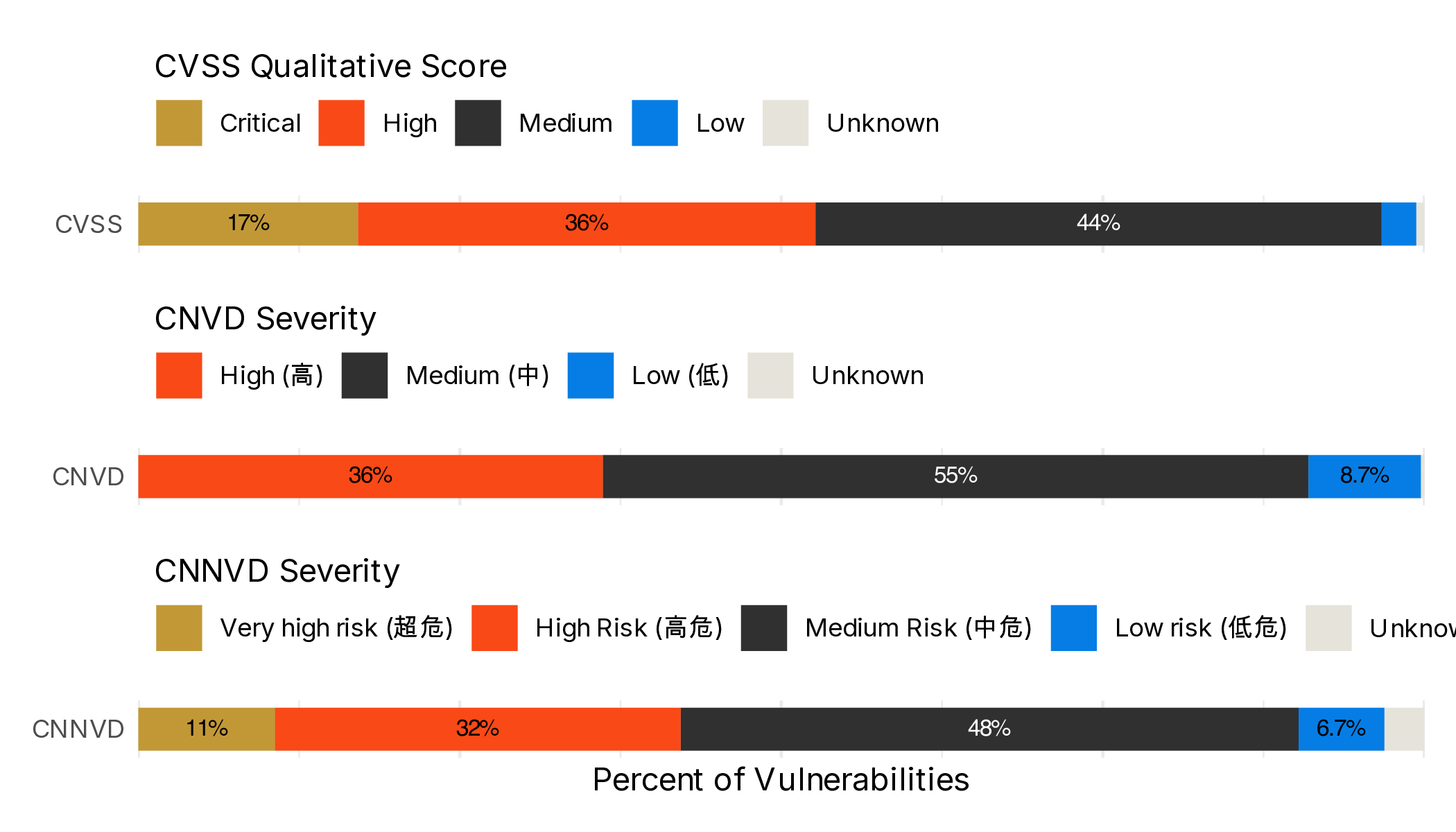

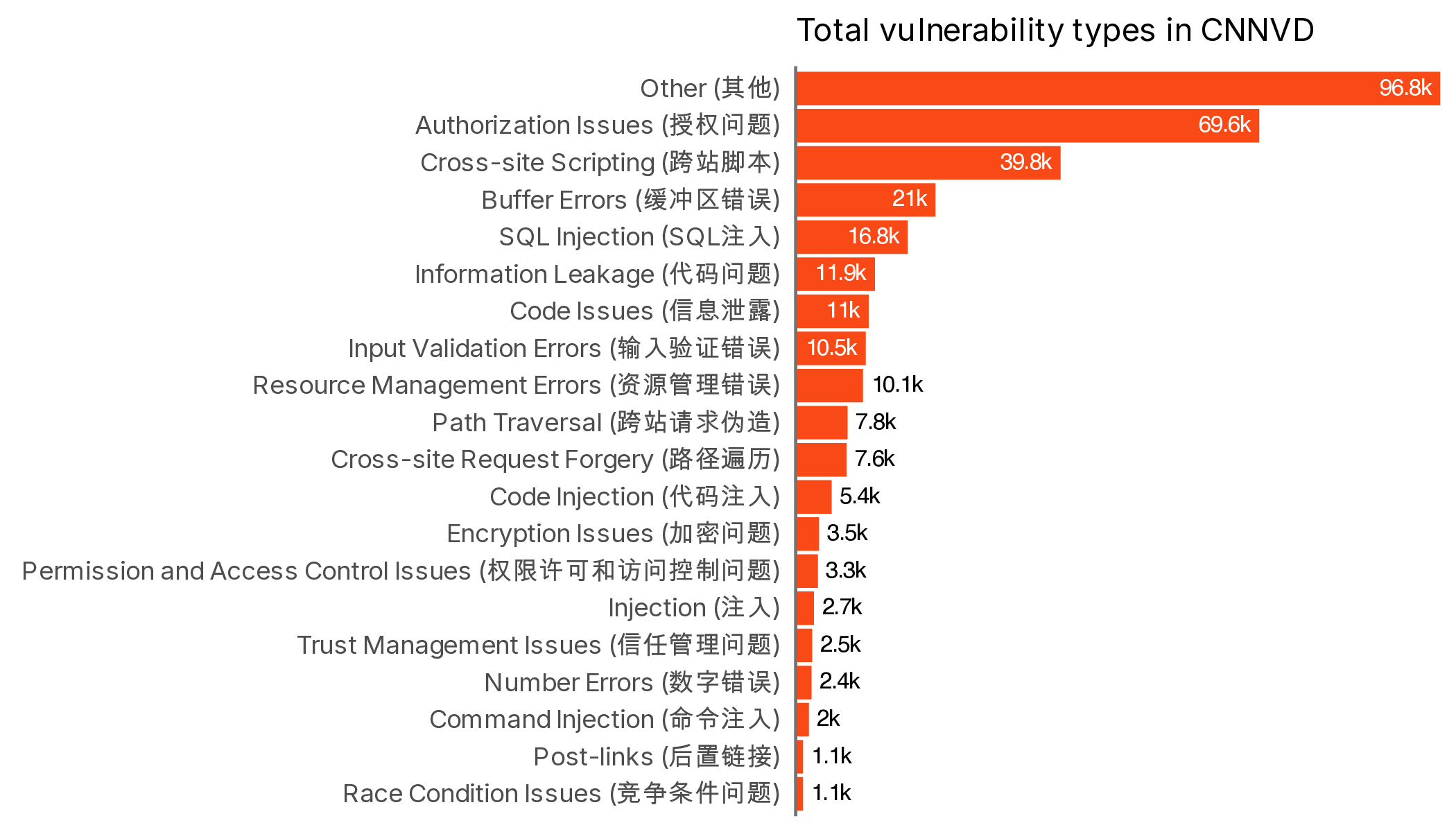

The schema outlined in Figure 2 should spark curiosity. First we focus on “severity.” These are all categorical with similar translated values to CVSS, but with similar distributions, though statistical testing (Chi Square Test) assuming the qualitative categories correspond as we think they might, they are technically “differently” distributed.3

At this point the analogous fields for the two databases end. CNNVD has a vulnerability type field that is similar to, but different from, CWE (though some better translation might make a more direct comparison).

There are two other structured and easily analyzable fields in CNVD: the open and submission times. These are, presumably, when the vulnerability was first submitted to the database and when it was finally published. Nearly all the vulnerabilities in the database (90%) claim to be published within a week of submission, with only seven paradoxically having a submission time later than an official open time.

The last unique data field, which does not have an easy analogy to the current CVE structure, is the

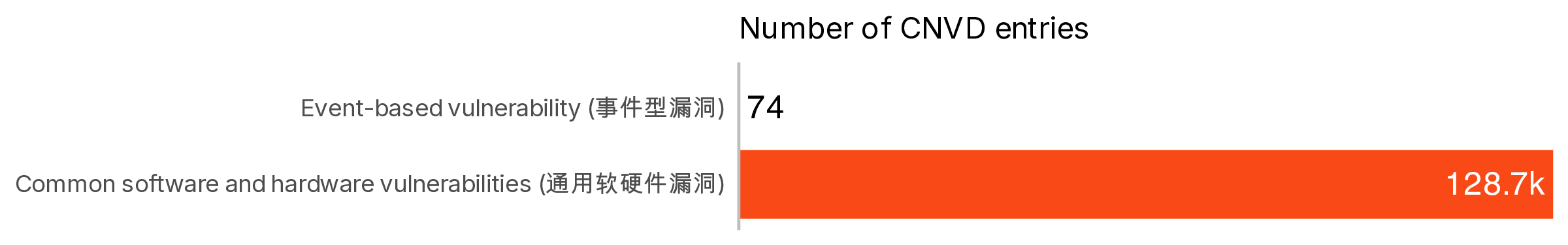

As can be seen in Figure 7, all but 74 entries in CNVD are labeled as “Common software and hardware vulnerabilities.” Of the 74 which are labeled “Event-based vulnerability,” they were all entered in the summer of 2020 and have the same flavor as CNVD-202-35587:

"Bitcoin Core is an open-source client used to verify the validity of blockchain transactions. Bitcoin Knots is a complete Bitcoin client. A security vulnerability exists in Bitcoin Core and Bitcoin Knots. An attacker could exploit this vulnerability to cause a denial of service (application crash) by using the same input twice."

That is they seem to be all relating to specific crypto currency thefts. Interesting to be sure, but not for the scope of this research, and if they are not more completely catalogued perhaps not even for those studying crypto currency incidents. Every other field in the two databases with the exception of one appears to not be structured or enumerated in any way and are simply free text.

CNVD-IDs, CNNVD-IDs, and CVEs

However, matching these vulnerabilities is not a straightforward task. A number of the entries in CNNVD and CNVD have errors making them difficult to exactly match. Many of the errors can be corrected and seem to be the result of typos (missing letters in CVE or leading numbers in the CVE Year field, “=” instead of hyphens, or “em-dashes” instead of regular dashes). While fixable, these errors suggest a degree of manual editing of the fields at some point rather than an automated system pulling data directly from the CVE list. CVE IDs themselves are easily validated and checked against an existing database; this is not the case with the rest of the fields, and this degree of errors in CVEs raises the possibility of errors in other fields, which we will confirm later. This will introduce friction for defenders attempting to search for particular CVEs (or other fields) within the databases against fixed values.

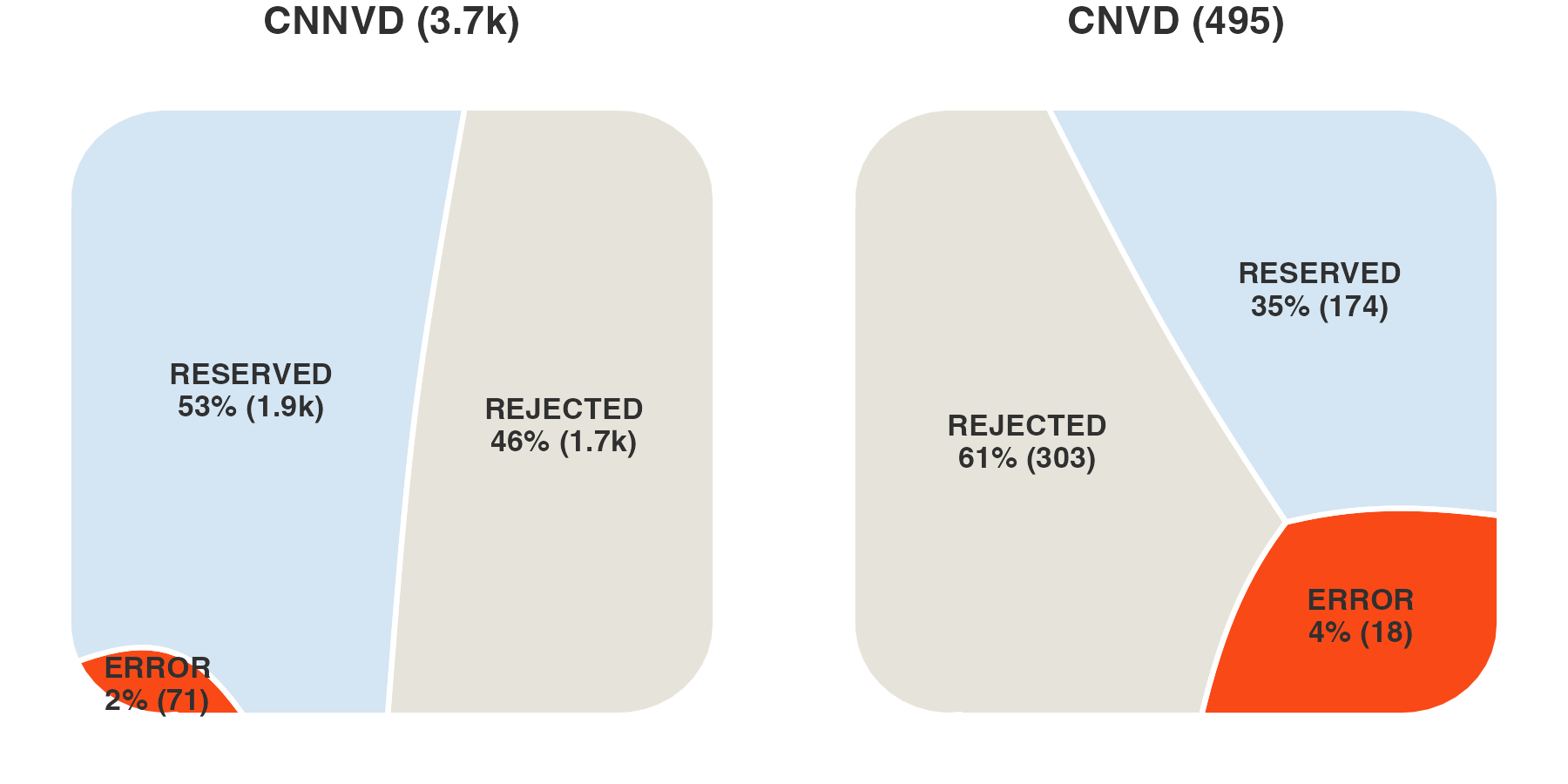

In addition to these errors, a number of CVEs are not yet in any public repository. Most are “RESERVED,” meaning a CNA has reserved a particular CVE ID for future use for a particular vulnerability. “RESERVED” CVEs need to be checked against MITRE’s API directly and are not published to any current lists. A small subset seem to be well formed (match the correct CVE format4), but do not correspond to any PUBLISHED, REJECTED, or RESERVED CVE. This (relatively small) subset of CVEs, we’ll call them ERROR, likely result in errors in hand entry that make them well formatted but not easily matched to extant CVEs. Other matching methods are possible and ongoing, however they are not yet covered here.

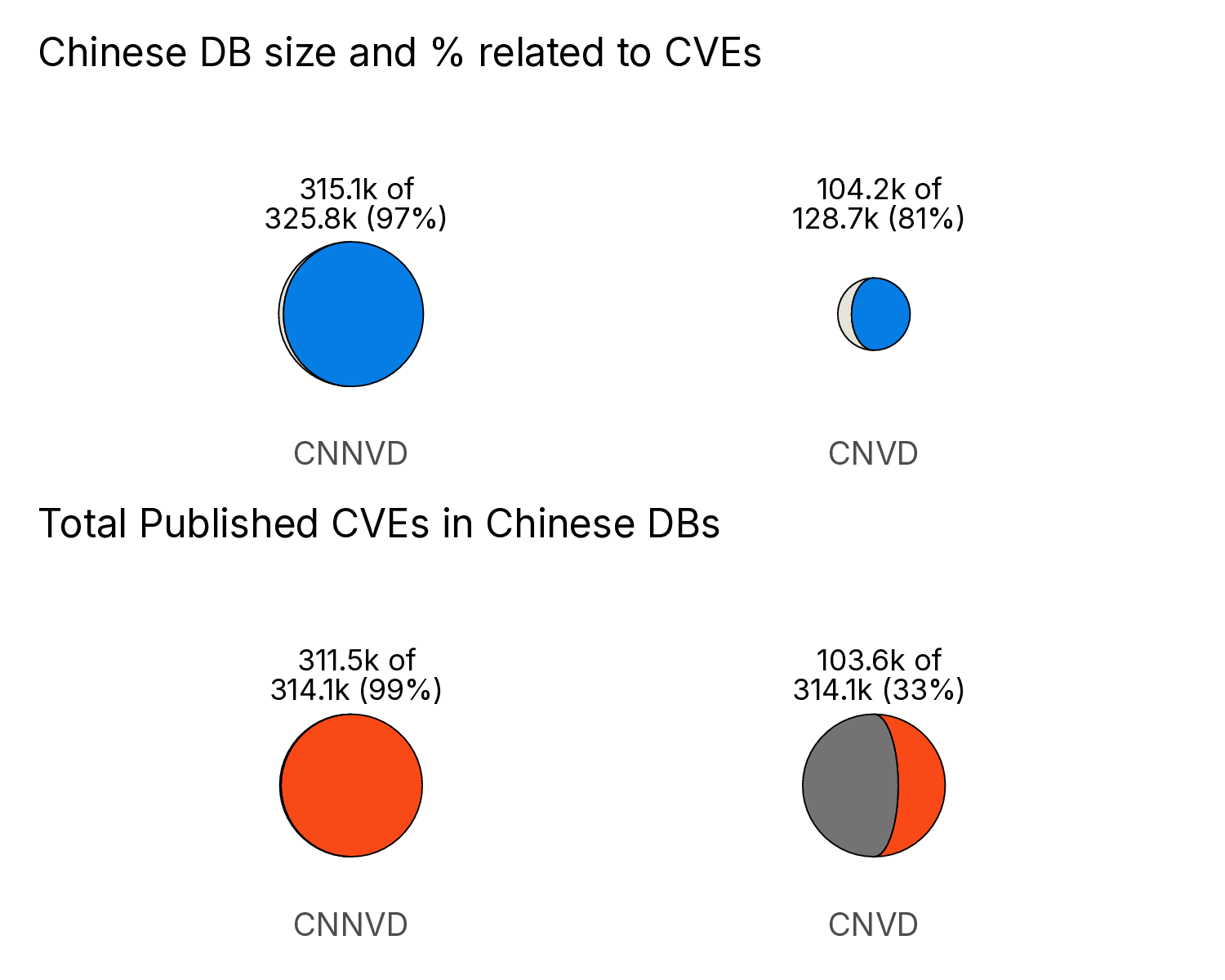

So let’s break it down, how many vulnerabilities in each of these databases are associated with CVEs and how many total published CVEs have corresponding CNVD or CNNVD IDs?

Among the mapped CVEs the vast majority of them are “PUBLISHED,” but for each database there are a significant number that are either “REJECTED,” “RESERVED,” or in error in some way.

Perhaps the most interesting question we can examine pertains to when these Chinese databases publish information in their databases relative to when data became public about the CVE. Initially, this seems like a pretty straightforward analysis given that all three sources of data have clearly marked dates. But vagaries in the CVE process mean that often a vulnerability is “Reserved But Public” (RBP), meaning that information about the vulnerability has been published and vendors and users are aware and actively patching, but for whatever reason the CVE process hasn’t moved it along into a “PUBLISHED” state. What this means is that often other databases such as NVD (or CNVD or CNNVD) can “publish” information about a vuln even though the official CVE list says “not yet published.”

We take an approach that gives the benefit of the doubt to the CVE program. We’ll say that a CVE is “published” when either CVE or NVD say it’s “published.” If a CVE was published more than 30 days after it was published in a Chinese database, we’ll take a look at the CVE reservation date and see if that is within 30 days of publication in the Chinese database. If so, we’ll assume this CVE is RBP and that the CVE reservation date was when it became available.

Before we proceed there is another wrinkle in the data, which is that some of the dates in the Chinese Database are on their surface incorrect. Specifically, there are a number of entries in which the month and year in the CNNVD or CNVD ID are not aligned with the publication date. Closer examination finds they are either set to January 1st of the publication year, or they have a year and month in the ID that corresponds to the CVE publication date but a CNVD or CNNVD date that is several years in the future or past. This is again another circumstance where it seems rather than having automatically generated timestamps when things are submitted and published, the databases are created by hand entry, leaving questions about the exact timeline of publication.

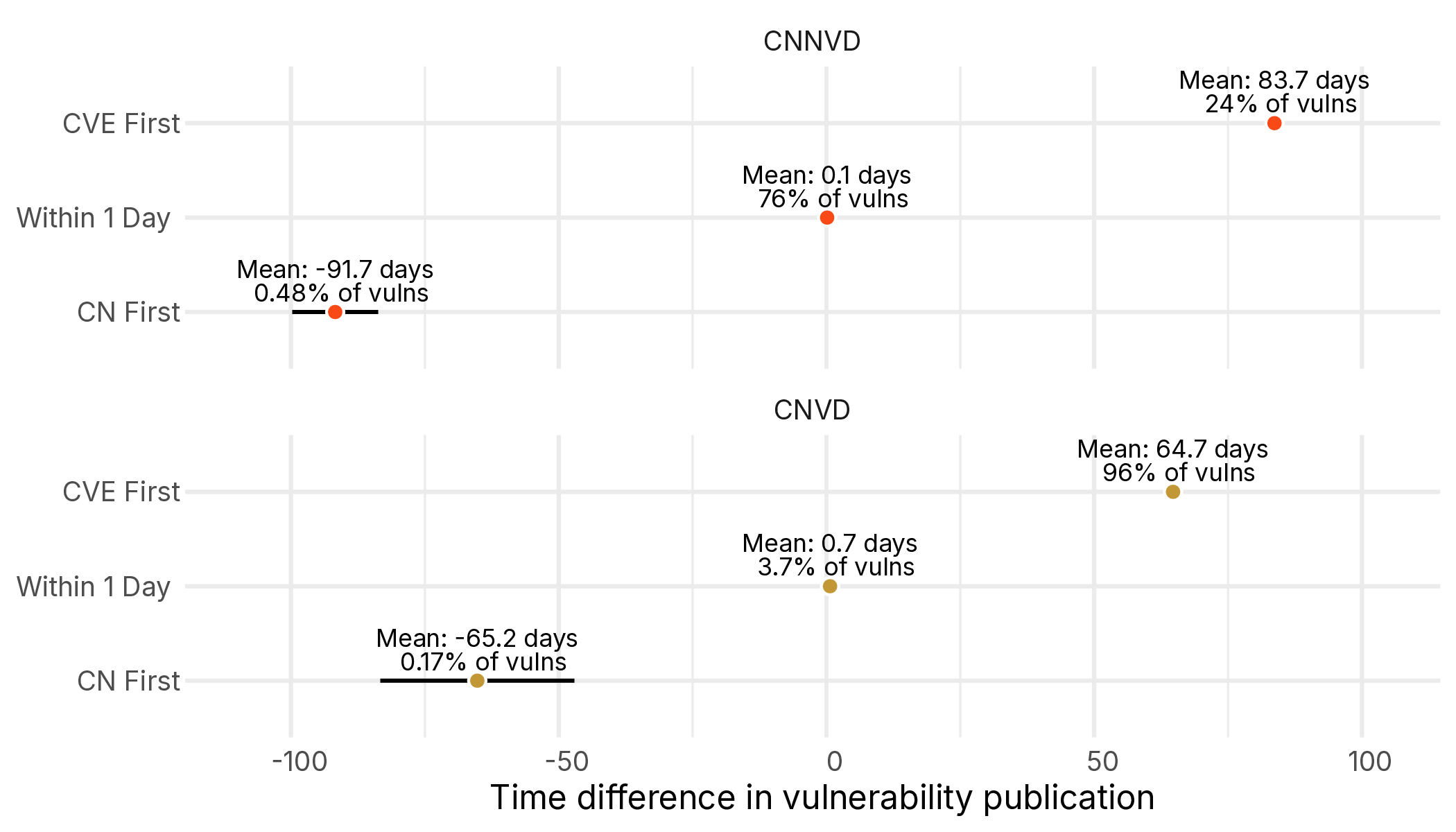

Given the somewhat convoluted (and admittedly hacky) logic to get us to a place where we can feel like we are correctly assessing the CVEs’ publication times, we can now examine “how often the Chinese Vulnerability Databases publish vulnerability information before CVE or NVD?” We’ll look at CVEs published since Jan 01, 2011 so we have approximately 15 years of data.5

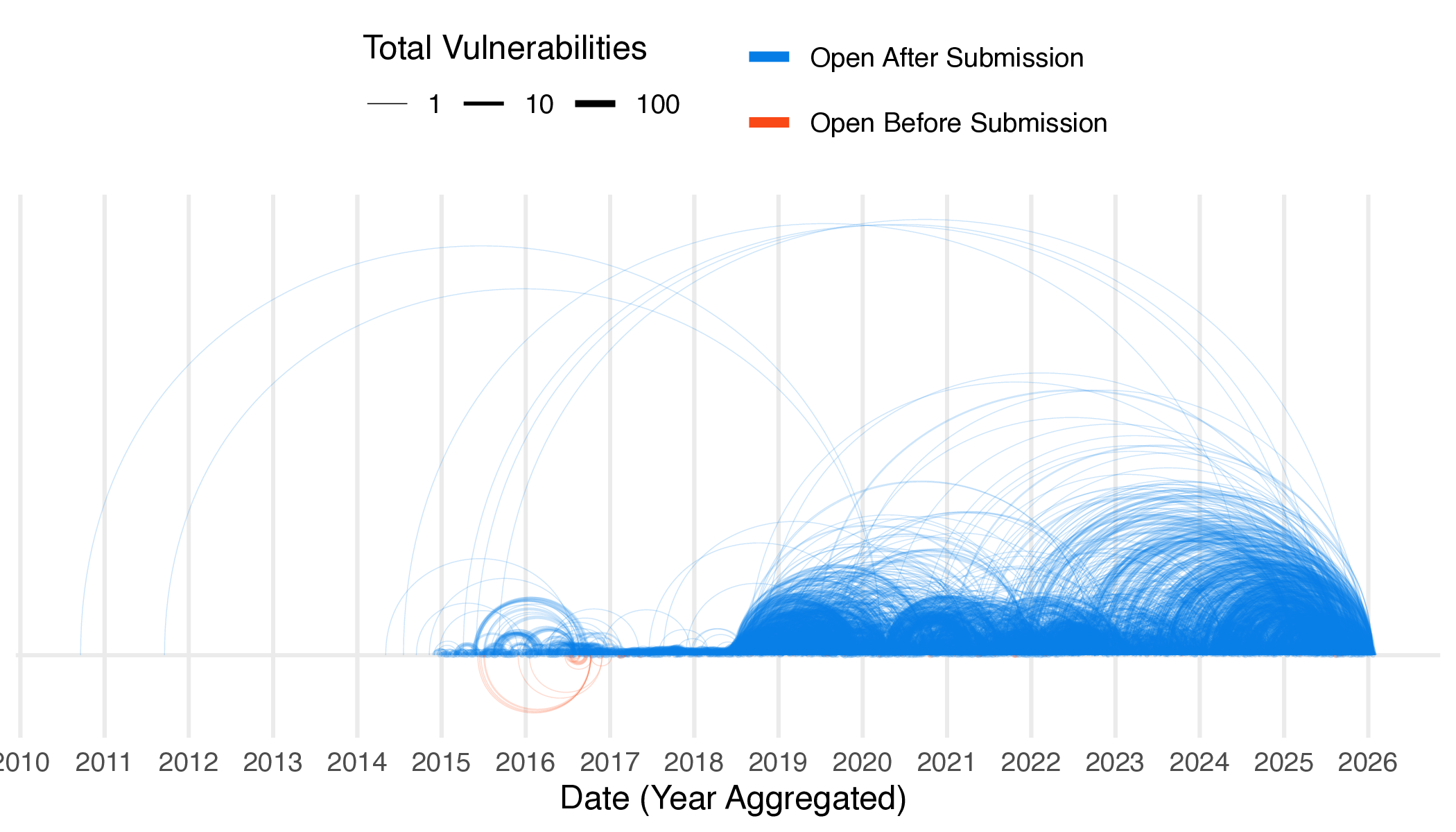

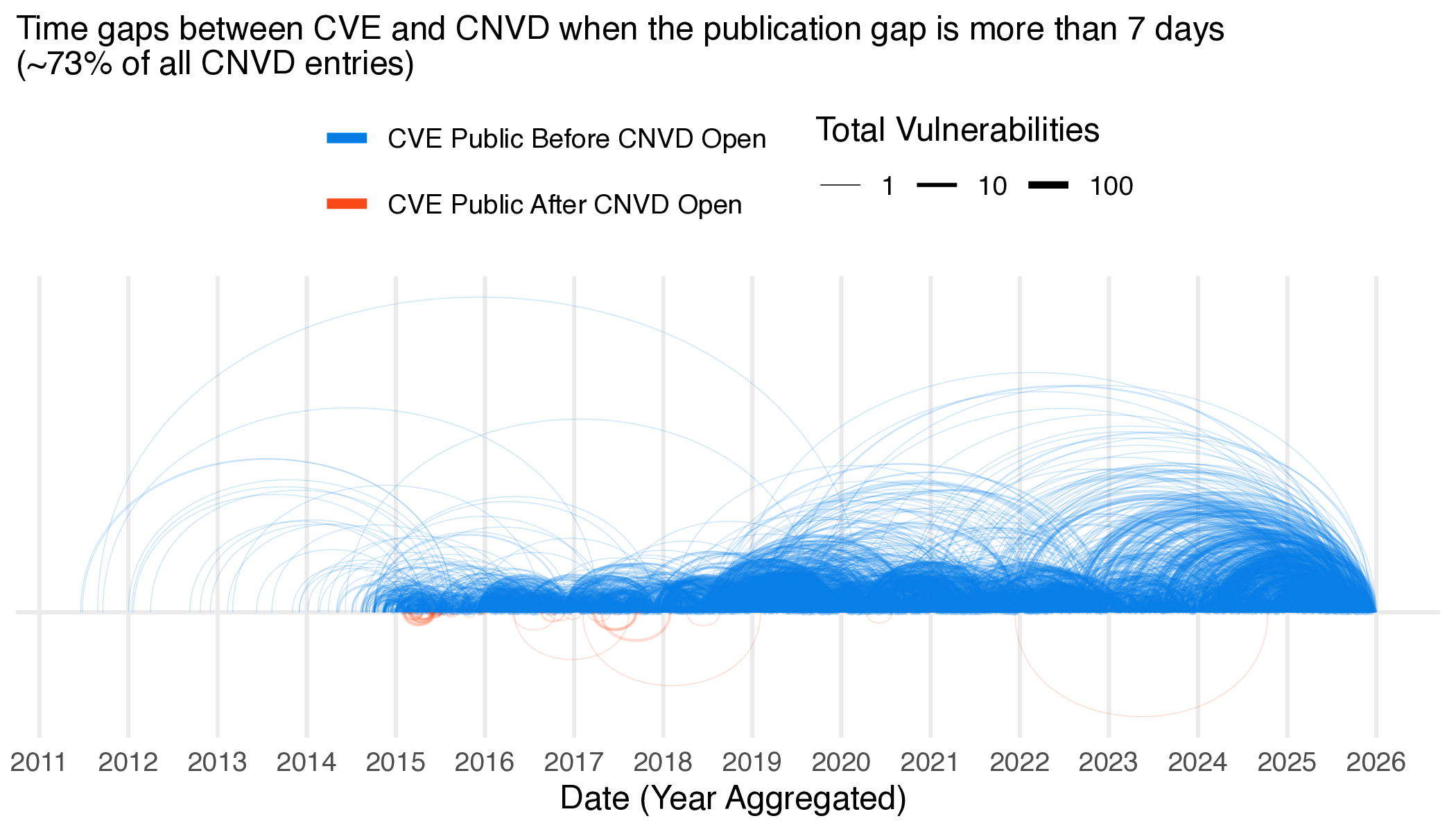

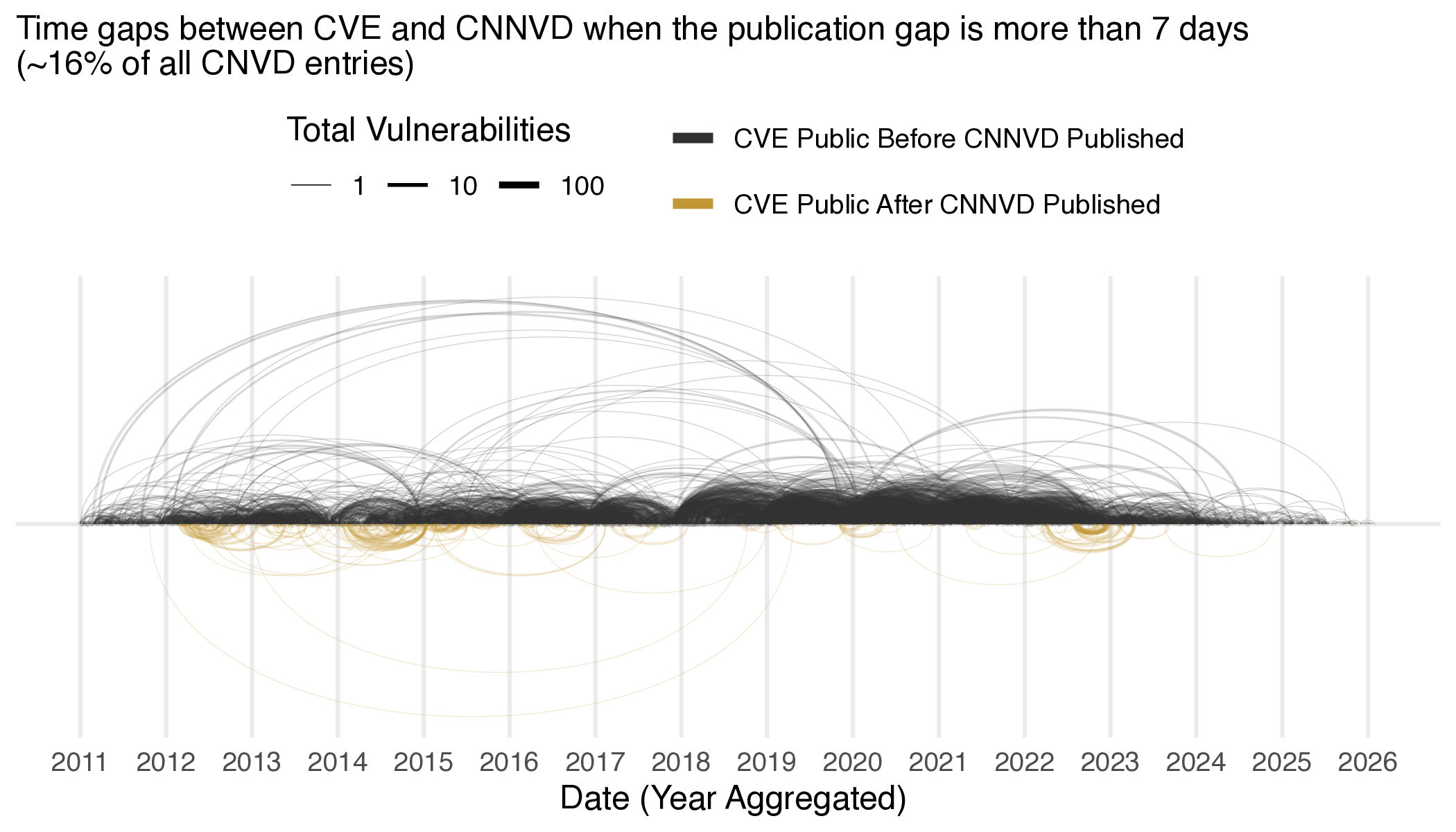

As we can see, for both databases the majority of vulnerabilities are published after or on the same day as the CVE is public. If we look at a few entries where there are large gaps in time (i.e. more than a week) we can see that they occur throughout the period of interest.

|

|

Figure 11 Difference in public information availability between vulnerability databases when the difference is more than 7 days. Arcs below the timeline indicate that the Chinese database was first, arcs above indicate that CVE or NVD was first. The higher the arc the longer the time gap.

Figures 10 and 11 demonstrate that some of the gaps can be quite long, but the majority of the time CVE is well ahead of the Chinese Databases, with only a small fraction published before (0.55% and 0.18% in CNNVD and CNVD respectively), totalling around 1,400 Chinese Database Entries. Notably, CNNVD is nearly always (84% of the time) within a week of the CVE publication, but CNVD is rarely so responsive, publishing within a week only 27% of the time. However, it is interesting that when CNVD or CNNVD beat CVE in publication, they do so significantly earlier (averaging around 3 months). Let’s look at a few examples:

|

CVE-2022-47375

Published: 2023-12-12

Reserved: 2022-12-13

Vendor Siemens

Description The affected products do not handle long file names correctly. This could allow an attacker to create a buffer overflow and create a denial of service condition for the device.

|

CNNVD-202208-5054

Published 2022-08-19

Description Siemens部分产品存在安全漏洞,该漏洞源于无法正确处理长文件名。攻击者利用该漏洞可以导致缓冲区溢出。

Description (Translated): Some Siemens products have security vulnerabilities stemming from their inability to properly handle long filenames. Attackers can exploit this vulnerability to cause a buffer overflow.

|

|

CVE-2022-4886

Published 2023-10-25

Reserved 2023-01-12

Vendor Kubernetes

Description Ingress-nginx `path` sanitization can be bypassed with `log_format` directive.

|

CNNVD-202204-4683

Published 2022-04-12

Description Ingress-nginx存在安全漏洞,该漏洞源于可以使用log_format指令绕过path清理。

Description (Translated) Ingress-nginx has a security vulnerability stemming from the ability to bypass path sanitization using the `log_format` directive.

|

|

CVE-2017-1002003

Published 2017-09-14

Reserved 2017-09-14

Vendor Invedion

Description Vulnerability in wordpress plugin wp2android-turn-wp-site-into-android-app v1.1.4, The plugin includes unlicensed vulnerable CMS software from

http://www.invedion.com.

|

CNVD-2017-03297

Published 2017-03-24

Description WordPress Wp2android插件存在任意文件上传漏洞,该漏洞源于应用程序未能充分验证用户提供的输入。

Description (Translated) The WordPress wp2android plugin has an arbitrary file upload vulnerability. This vulnerability stems from the application's failure to adequately validate user-provided input.

|

|

CVE-2016-9562

Published 2016-11-23

Reserved 2016-11-22

Vendor SAP

Description SAP NetWeaver AS JAVA 7.4 allows remote attackers to cause a Denial of Service (null pointer exception and icman outage) via an HTTPS request to the sap.com~P4TunnelingApp!web/myServlet URI, aka SAP Security Note 2313835.

|

CNVD-2016-06754

Published 2016-08-26

Description SAP NetWeaver Application Server Java存在拒绝服务漏洞。攻击者可以利用漏洞导致拒绝服务条件。

Description (Translated) SAP NetWeaver Application Server Java has a denial-of-service vulnerability. Attackers can exploit this vulnerability to cause a denial-of-service condition.

|

Table 1 4 Example CVEs and their corresponding CNNVD and CNVD entries where the CN entry is published before the CVE.

Table 1 gives a few examples of CVEs where the CNNVD and CNVD managed to publish the vulnerability ahead of where the CVE was published. All are more than 3 months ahead of the publication by CVE. Remarkably, most of the translated descriptions are a very close match to descriptions provided in the CVE entry. This raises a number of questions about what the original description was and when it was added to the Chinese Databases. Unfortunately neither database has an easily accessible changelog, so it’s unclear when these descriptions are being added. One aspect of the vulnerabilities we can study is their assigned severity in the Chinese databases and whether it differs substantially depending on who is first to claim to publish.

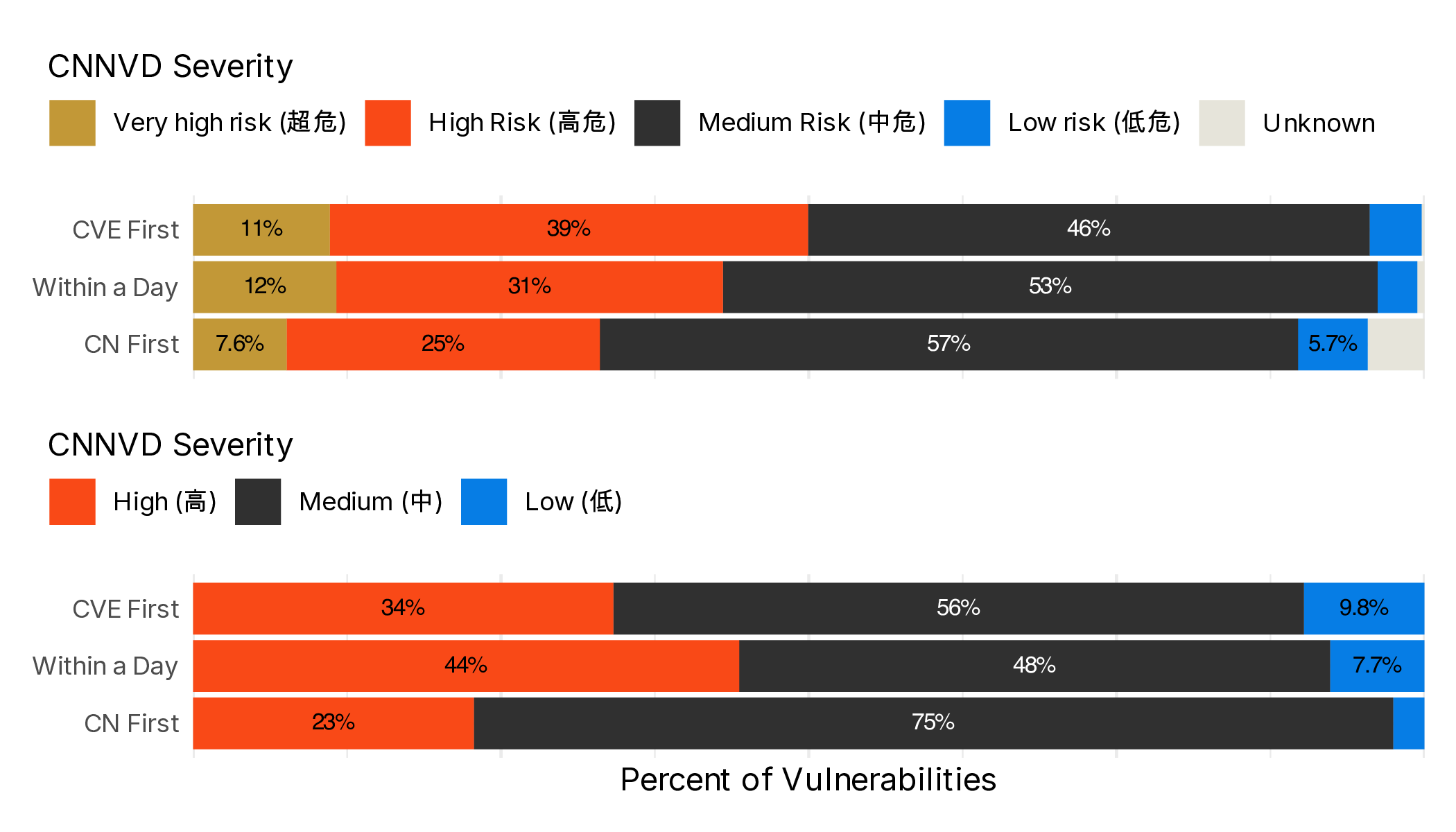

Figure 12 indicates that when China is the first to claim publication there is a skew (statistically significant skew) towards lower severity vulnerabilities. It also specifically seems to be the case that for CNNVD a substantial amount of the “Unknown” severity vulnerabilities are those in which China publishes first. This indicates that these Databases are likely relying on Western sources for severity scores.

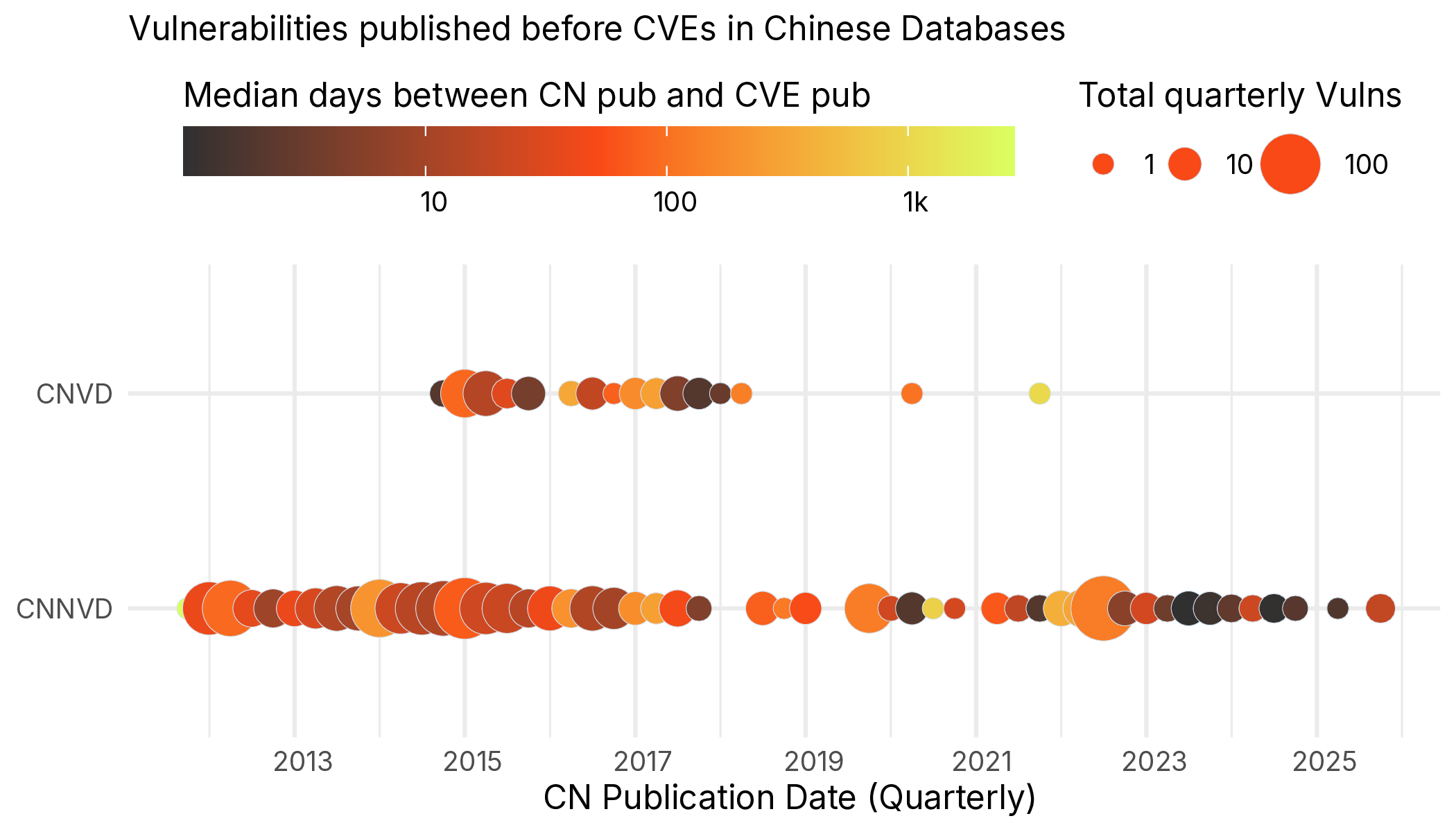

We leave future research to examine exactly what the nature of vulnerabilities (Vendor, Type) that are published in Chinese databases first. While the arc diagrams in Figure 11 give us some clue about when and how much sooner these vulnerabilities are published, we are a bit more explicit in Figure 13.

There is no real discernable or detectable pattern with vulns. CNVD has many fewer early birds, and more recently (since late 2021) there are none, whereas CNNVD is publishing more across the board, even very recently.

We note that when looking at examples we found yet still more errors. For example, CNVD-2016-02472 was initially linked to CVE-2016-8741 and seemed to indicate that CNVD had beat CVE to publication by nearly half a year. But upon closer examination of the translated description, it became clear that the vulns were unrelated and that CNVD-2016-02472 identified CVE-2016-0741 (a single typo), and that CNVD published this only two days after CVE did. A more thorough examination of translation of relationships and matching using machine translation is needed, but beyond the scope of the current work.

CNVD/CNNVD IDs without CVEs

The next obvious question is how many vulnerabilities in each of these databases are not linked back to specific CVEs and may represent unknown vulnerabilities in the western security world?

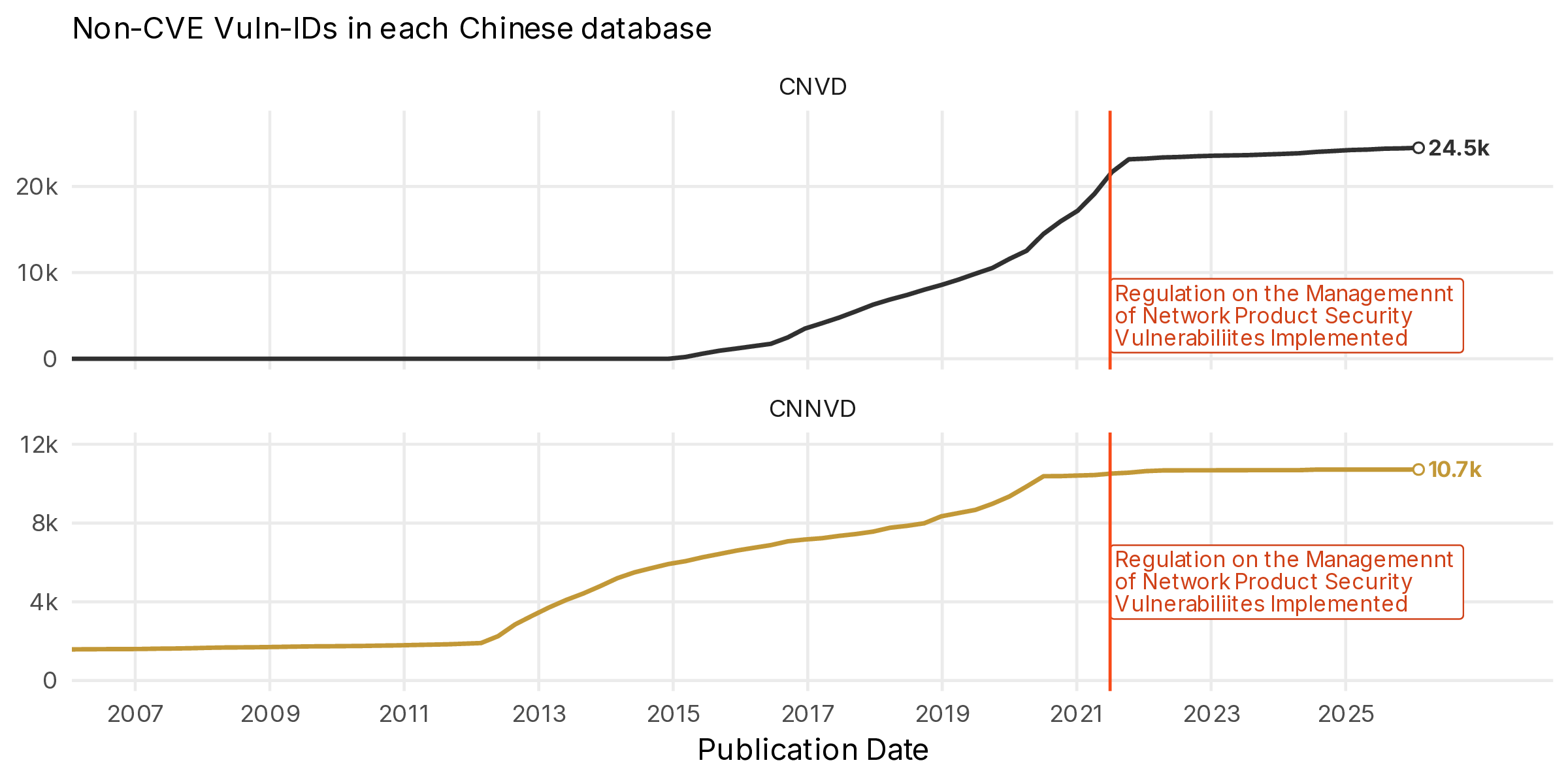

Figure 14 shows a marked transition around the time the new regulations were implemented by the Chinese government. However, both databases do not make a change at the same time. CNVD, which, recall, is maintained by CNCERT, transitions to a slower rate of publication after the new regulations. In contrast, CNNVD, which is maintained directly by the Ministry of State Security, began slowing down their publication of non-CVE vulnerabilities nearly a year prior to the new regulation. However, we have seen a marked increase in new publications in CNNVD in the last year.

There are several obvious possibilities here that may explain the change.

- Mapping between the Chinese databases and CVEs was inconsistent and around the time of the regulation the databases endeavored to do the mapping more consistently. Similarly, it’s possible that in 2025 CNNVD simply gave up mapping vulnerabilities to CVE.

- The Chinese databases were willing to publish non-CVE vulnerabilities prior to the regulatory change, but afterwards these vulnerabilities are being kept from the public eye.

- There are vulnerabilities in which Western Databases have not released IDs for because they are simply in software or devices that are not in use in the western world.

The answer is likely a mix of all three, which can be seen by examining and translating some of the vulnerability descriptions of some of these vulnerabilities.

| CNVD-2024-48432 | CNVD-2021-03304 | CNVD-2025-07703 |

| SIMATIC PCS neo是一款完全基于Web的过程控制系统。 Siemens SIMATIC PCS neo存在缓冲区溢出漏洞,未经身份验证的远程攻击者可利用漏洞执行任意代码。 |

OneDrive是微软新一代网络存储工具,由SkyDrive改名而来。OneDrive的版本跨越多个终端,网页版、移动端、PC端。 Microsoft OneDrive存在DLL劫持漏洞,攻击者可利用该漏洞导致用户电脑被远控或者植入木马。 |

上海上讯信息技术股份有限公司运维管理审计系统存在命令执行漏洞 |

| SIMATIC PCS neo is a fully web-based process control system. Siemens SIMATIC PCS neo has a buffer overflow vulnerability that could allow an unauthenticated remote attacker to execute arbitrary code. |

OneDrive is Microsoft's next-generation online storage tool, rebranded from SkyDrive. OneDrive is available across multiple platforms, including web, mobile, and PC. Microsoft OneDrive has a DLL hijacking vulnerability, which attackers can exploit to remotely control users' computers or install malware. |

A command execution vulnerability exists in the operation and maintenance management and audit system of Shanghai Shangxun Information Technology Co., Ltd. |

| CVE-2024-33698 | None (Vaguely similar to CVE-2021-40444, but published much earlier) | None |

Table 2 Three different CNVD vulnerabilities without explicit mapping back to CVEs.

The first column in Table 2 likely represents the case where this vulnerability was simply never mapped to a CVE and matches the description and time of publication of CVE-2024-33698. The second column, however, vaguely describes a DLL injection vulnerability in Microsoft OneDrive. While similar CVEs exist, the most obvious candidate for this CNVD ID was not published until some 9 months after the CNVD ID was published. The final column is a vulnerability in a piece of telecommunications equipment that we assume is almost exclusively used in Asia.

Given the inconsistent ways data is included in Chinese Databases as well as CVE and NVD, we are also performing some NLP analysis on this data to improve this mapping and better link these vulnerabilities to CVEs. Stay tuned for our follow-up.

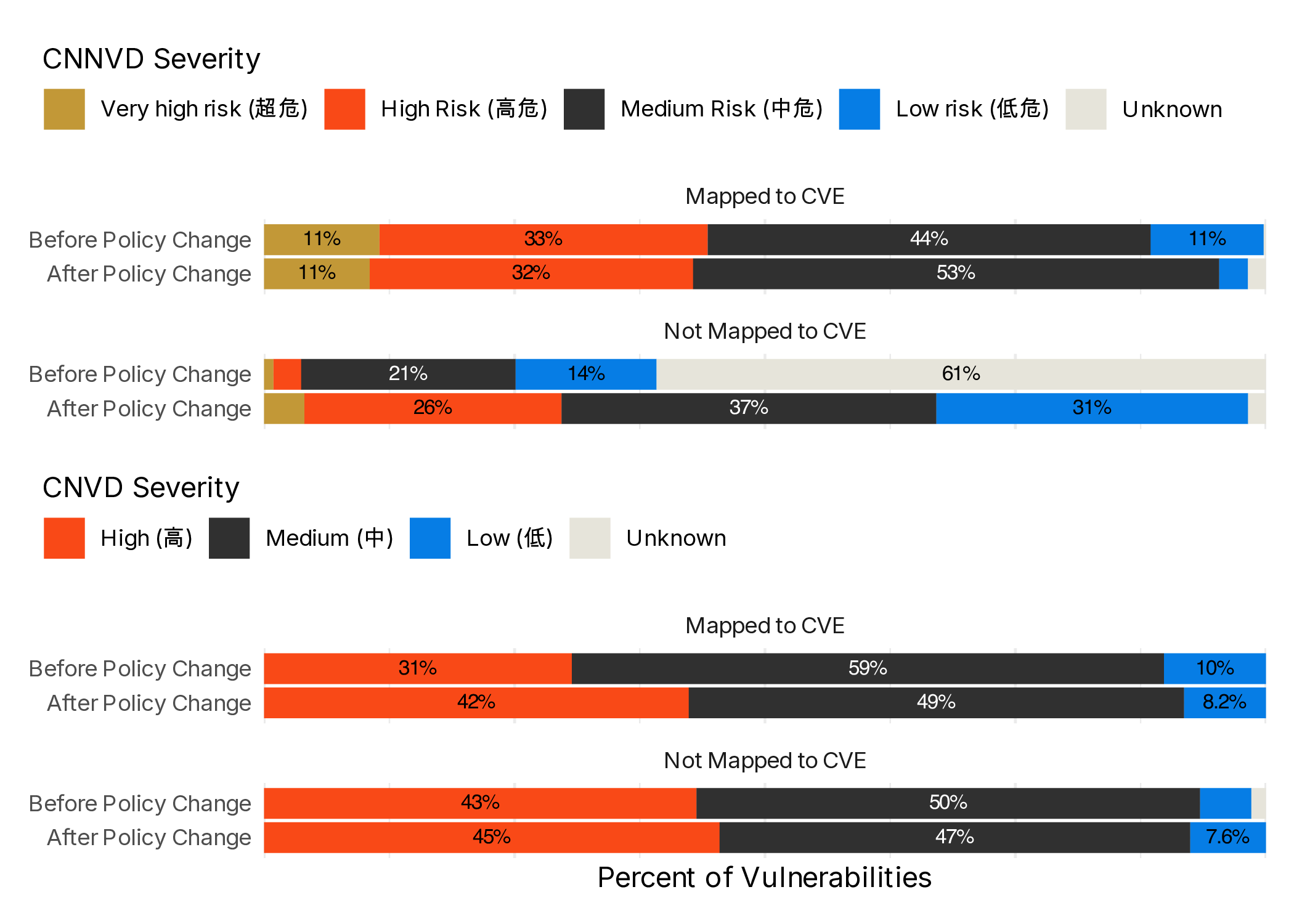

Finally, we want to turn to whether the severity of vulnerabilities changes substantially around the time of the regulation change and whether the severity distribution is different between vulnerabilities that can be mapped to CVEs and those that can’t. This is particularly relevant given that the regulations state that vulnerability severity cannot be overstated.

Interestingly Figure 15 does not indicate a substantial change in the severity of vulnerabilities with a policy change, with the exception of CNNVD now being nearly complete about providing vulnerability severity after that change.

Conclusions

This foray into one country’s dissemination of vulnerability information gives us a glimpse into what the attack surface landscape might be outside of the United States and Europe. Given the current worries among some about the future of the CVE program, it is certainly worth it to simply look at what else is out there.

When we do dive into these databases a few useful conclusions can be drawn. Historically, these databases have followed the US lead with respect to vulnerabilities, partially mirroring CVE publication. However, this is a fact that may be changing. Indeed the policy language in the July 2021 policy change by the Chinese Communist Party indicates tighter domestic control over the publication of vulnerabilities. Evidence currently suggests that CNVD and CNNVD are focusing on a publishing strategy that will do the most for securing the Chinese public.

The other major contrast we can draw is that for all the quality and consistency problems with the CVE infrastructure and wider ecosystem, it still stands head and shoulders above what is publicly available from China. Standardized, complex frameworks such as CWE, CPE, and CVSS give detailed information about public vulns that is consistently machine readable to feed into a variety of systems. This has allowed the spawning of multiple other extended frameworks such as Known Exploited Vulnerability lists and scoring systems like DVE and EPSS. This is enhanced by the ecosystems’ federated nature and unifying ID in which an assigned CVE-ID can allow researchers to easily share and pivot off information. This is a feature lacking in the current Chinese vulnerability ecosystem.

Lastly, forward-looking security leaders should be making contingency plans for how they are going to manage vulnerabilities in a world where CVE or other western ecosystems may have blind spots into the risks they are facing. This work highlights some of those blind spots, but is only of one country. As we mentioned in the introduction there are others in the world doing their own work which may necessitate closer examination and an even broader future view.

1 There are of course automated headless browser ways to do this, but it is quite a step more complicated and unreliable than more open APIs.

2 Dates are a challenge with the databases as well. Some of the Chinese databases include dates which are marked as “1900-01-01” the default date for microsoft products. This likely indicates that the date is missing. Where applicable (such as when making date based comparisons) these vulnerabilities are excluded from analysis.

3 We note that in the xml schema for CNVD “serverity[sic]” is only listed as categorical levels, however, individual vulns on the website have what appear to be CVSSv2 vectors even for recent vulnerabilities.

4 CVE-\d{4}-\d+

5 Going back further does not qualitatively change the results, but things get a bit stranger the further back you go, with claimed publications all the way back to 1988, which seems… implausible. While we aren’t saying that pre-2011 vulns are important (some still get exploited), but a focus on the recent past is reasonable.