Ransomware, breach sharing, stealer logs, credentials, and cards. What has shifted and how to respond.

On the Move: Fast Flux in the Modern Threat Landscape

Tags:

Executive summary

This report details an investigation into a Fast Flux network observed in 2024. It covers the technical details of the network, its observable infrastructure, the malware associated with it, and its presence on the dark web.

- Observed 193 domains in 2024, 42 of which were used as nameservers.

- Tracked 2960 unique IP addresses, with 82% originating from 10 countries.

- Mapped the IPs into Internet Service Providers, indicating the use of residential IPs.

- Service is associated with the 2016 Dark Cloud/Sandiflux botnet.

- Classified 87 client domains: 44 as C2s, 27 as droppers, and 16 as websites.

- Darkweb shows activity related to fast flux services dating back to 2008.

- In 2024, at least four Bullet Proof Hosting (BPH) services announced fast flux, with prices starting in the low hundreds of dollars per domain.

Introduction

In the wide landscape of cybercrime, malicious actors are constantly seeking methods to improve their operations’ resilience and stealthiness. When it comes to maintaining a resilient infrastructure, different techniques can be used at different points of the infrastructure stack. An example of a technique used at the DNS level is Fast Flux. Recently, we observed this technique being used by a threat actor we're researching and started tracking the associated Fast Flux service.

This blog post will present our findings, which include the observable infrastructure, uses of the service, malware associated with it, and dark web activity. With this post, the reader will gain a better understanding of the ecosystem of fast-flux networks and why an old technique is still considered a relevant threat by today’s standards.

Fast flux 101

Fast flux is a technique used by threat actors to make their malicious infrastructure more resilient, harder to trace, and more resistant to takedown efforts. This evasion technique was originally defined in 2007 by The Honeynet Project in one of their Know Your Enemy (KYE) paper series, and it can be briefly described as a method that rotates DNS records for a given domain at short intervals (e.g., 3 minutes). This is commonly implemented by having a single domain with multiple IP addresses assigned to it, and a small Time to Live (TTL) record. This ensures the records are cached for small periods of time, allowing the service operators to switch the resolving IPs frequently.

Beyond this simple implementation at the domain level, dubbed single-flux, there’s also a more robust version named double-flux, where not only the domain’s IP addresses are rotated frequently, but also the nameserver’s IP addresses. In practice, we would observe both the records for the domain and the nameserver associated with that domain having multiple IP addresses assigned to them, and a small TTL.

Technical details

In this section, we’ll dive into the technical details of the fast-flux service we observed. We’ll start by quickly describing how we encountered this service being used, followed by how we tracked it to get an overview of its historical usage. We’ll also briefly look at the potential malware that enables this service, and we’ll finish with examples of what this service has been used for.

One of the data sources we use to assess risk is Bitsight’s proprietary compromised systems dataset. To accurately build this data source, Bitsight tracks malicious groups, the malware being used, and the infrastructure behind it. This is done by sinkholing and emulating the malware network protocol, and an example of a well-known malware we track is SmokeLoader. This family is sold as a Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS), and one of its botnets was relevant enough to have an EUROPOL operation disrupt it. This specific botnet is where we found the fast flux service being used in the domains used as Command and Control (C2).

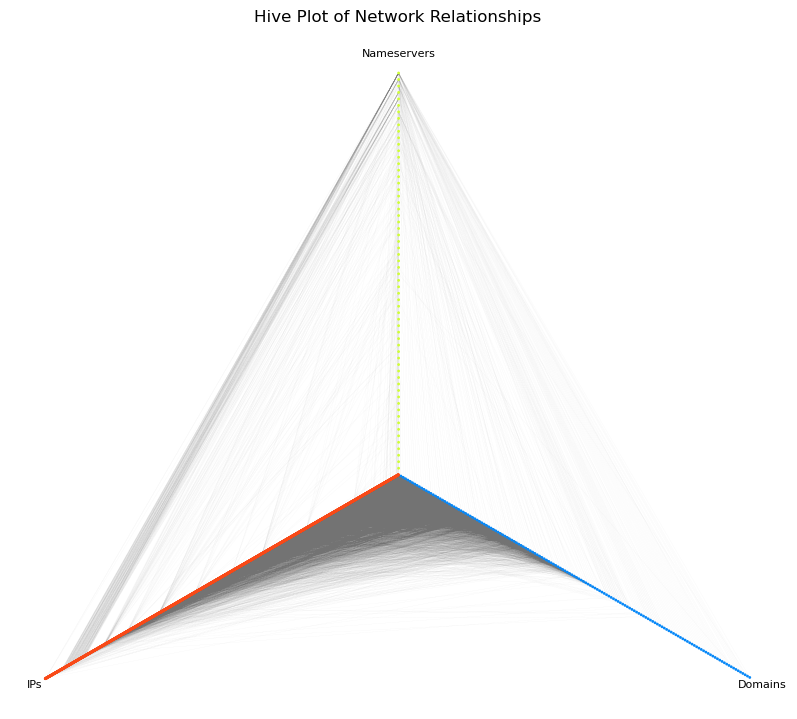

The fast flux service in question is of the double-flux type, where both the domains and nameservers have a small TTL and multiple IP addresses assigned to them. An example of a nameserver (green), its corresponding domains (blue), and their IPs (orange) for the year 2024 can be seen in Fig. 1 below, which gives a visual representation of the network.

Collection methodology

With the knowledge that this service was of the double-flux type, we now describe our data collection methodology, which takes the type into account to try and maximize the discovery of both domains and IPs. In the following description, we use the name “domain” to reference the domain that is being used by a client of the service, and the name “nameserver” to reference the domains used as nameservers for a client domain.

We started by manually investigating some of the domains and IPs that were using the service, and since we’re dealing with a double-flux service, we knew that for a given nameserver X, if we looked at historical DNS for domains using X as its nameserver (NS record), we would discover domains that were part of the service. From this starting point, we could look for A records for a given domain, discovering IP addresses that were part of the service. We do this process recursively to pivot from IPs to new domains/nameservers and pivot from domains/nameservers to new IPs.

The drawback in this approach is that it assumes that different clients share the IP pool and nameservers, if they do, we have a relatively clear and complete view of the infrastructure behind the service, if they don’t, we end up only observing a smaller subset of the infrastructure, used by a small number of clients, or in the worst case by a single client.

After collecting the data, we obtain 2 types of relations: IPs for every domain and nameserver, and nameservers for every domain. To reduce redundancy in the data, we chose to focus on domains and ignore subdomains. The reasoning behind this is that most of the subdomains were from nameservers (e.g., ns1.domain, ns2.domain), and the few remaining weren't shown due to wildcard matching for 2 domains.

Observable infrastructure

Between January 1st, 2024, and December 31st, 2024, we observed a total of 193 domains, of which 42 (22%) were used as nameservers, and 26 (13%) never had an `A` record. During that period, we observed 2960 unique IP addresses, where the average IPs for each domain was 151, with the highest number of unique IPs for a single domain being 1582, and the lowest being 1. Looking at the numbers from the IPs side, the average of domains for each IP was 7, with the highest number being 82, and the lowest being 1.

The following Fig. 2 shows the number of unique IPs and domains we observed per month. Comparing the number of unique IPs and domains throughout the year, we can note that while domains remain stable, IPs vary considerably. This could indicate there’s a significant difference in how the service is being used, with some domains having a higher pool of IPs than others, or that the IPs are dynamic and the endpoint of the fast flux rotates IP often.

To better understand the connections between IPs, domains, and nameservers, Fig. 3 below shows a hive plot of the infrastructure. This plot contains 3 concentric axes, one for nameservers, one for domains, and one for IPs.

The network elements are placed in their corresponding axis ordered by degree centrality (i.e.: fraction of the nodes they’re connected to), with the IPs and Domains having decreasing centrality from the center (i.e.: nodes closer to the center have more connections), and Nameservers have an increasing centrality from the center (i.e.: nodes closer to the center have fewer connections). An edge between nameservers and domains represents an `NS` record, and an edge between nameservers and IPs, or domains and IPs, represents an `A` record. The denseness or sparseness of the edges gives us an idea of clusters between the axes.

This plot gives us a sense of how the infrastructure interconnects, specifically how there are different IP pools for different segments of the infrastructure. There’s a large pool of IPs used for the domains (edges from IPs to Domains), while a smaller subset of IPs is used for the nameservers (edges from IPs to Nameservers), with some almost exclusively used for nameservers (IPs further from the center).

Without a full visualization of infrastructure and limited knowledge of how the fast-flux service is implemented, we can only hypothesize how to fully interpret the clustering on the plot:

- Different clients are allocated different IP pools

- There are different tiers of the service - based on the size of the IP pool

- Some IPs are more reliable than others - used for nameservers, or for a higher tier of the service

Besides the observed clustering, we can also note that there are domains that don't have any IPs assigned (domains at the end of the axis), while having nameserver records. We can only speculate on why we observed this: our data could be incomplete, the domains were never used, or the domains are yet to be used.

At this point, we have a fair understanding of how the infrastructure is interconnected. We'll now look more into the IPs that are part of this service. Specifically, we’re interested in knowing their geolocation and entity information, which can give us more insights into the fast-flux service.

We'll start by looking at the geo-distribution of the IPs, which can be seen in Fig. 4 below. The IPs were from 73 different countries, with the highest number of IPs for a single country being 831, and the lowest being 1.

We can note how a small number of countries hold most of the IPs. More specifically, 82% of all IPs are from 10 countries: Mexico, Argentina, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, the Dominican Republic, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Uruguay, Egypt, Chile, and Colombia. The following table shows the exact numbers for each top country:

| Country | MX | AR | MA | SA | DO | BA | UY | EG | CL | CO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unique IPs | 831 | 324 | 250 | 244 | 198 | 140 | 130 | 121 | 110 | 93 |

Using our internal dataset of mapped entities, we extracted the sectors and entities associated with the IPs to better understand what kind of IPs are hosting the infrastructure. From the 2960 IPs, we were able to map 1976 (66%). Of these, 1861 (94%) are associated with Telecommunications, 114 (5.8%) with Technology, and 1 with the Finance sector.

The most interesting association is the single IP in the Finance sector. We did confirm this is not a false positive, and that the IP was being used by 17 domains between 2024-05-10 and 2024-07-29. Likely, the organization operating this IP was unknowingly participating in the fast flux network.

The remaining sectors (Telecommunications and Technology) fall into ISP entities, which point to the usage of residential IPs to serve the domains. This also raises one relevant point: if the IPs are residential, they can be dynamic IPs, which explains why we see a high number of unique IPs, but in reality, the number of endpoints serving as reverse proxies might be significantly smaller.

Malware connection

From what we observed in the infrastructure, we had a strong suspicion that this service was using compromised machines as reverse proxies. By interacting with the IPs that were part of the service, we were able to identify that they were all serving the same self-signed TLS certificate. From this indicator, we found a 2021 blogpost (recently updated) that associates this certificate with a 2017 malware sample.

By also pivoting on some of the domains hosted in the service, we found multiple articles (e.g, 1, 2, 3) that connect this service with the Dark Cloud/Sandiflux botnet, which is known since at least 2016 and was used by different groups to distribute malware, ransomware, and to host carding sites.

The botnet behind this service was not the focus of our malware analysis. However, we have high confidence in the connection between this service and the botnet based on evidence linking the indicators we observed to previous research. We believe that there’s some interesting future work to understand how this botnet operates since it has been active for over 8 years.

Service uses

One other topic we want to look into is how this service is being used. We already mentioned that we stumbled upon this service because of its usage by one of SmokeLoader’s botnets, but in this section, we’ll look into the other domains that were also using this service and try to classify them. To classify the domains, we’ll use our internal dataset of network indicators and external datasets to cross-check and validate the data. We’ll group the domains into types as follows:

- C2s - used as command and control.

- Droppers - used to host binary files

- Websites - host an actual website.

And we’ll classify them as the associated malware (if we’re able to classify them) or as:

- Creds - for websites that host stolen credentials forums

- Phishing - for a phishing website

- Leaks - for websites that host leaked data

- Unknown - if we cannot classify the domain

We’re able to classify 87 (45%) of the domains we’ve observed. Of the classified domains, 44 (50%) were used as C2s, 27 (32%) were used as droppers, and the remaining 16 (18%) were used as websites. Fig. 5 below shows how the domains were classified, with the majority being used by SmokeLoader as either C2s or droppers for the malware. We can also note a greater variety of classifications for droppers and websites, while the remaining are evenly divided between other classifications.

The previous graph shows some interesting classifications that we believe need clarification:

We’ve classified one domain as belonging to the Emotet family, which is not active anymore. From our analysis, the domain was used by Emotet in 2022, but from December 2023 to January 2024, it started using nameservers that belonged to the Fast Flux network, and consequently, the domain was being resolved to IPs that belonged to the network. We do not have a clear justification for why this happened.

The phishing classified websites seem to be targeting the Arculus crypto cold storage wallets with a fake firmware upgrade. By glancing at the Arculus subreddit we can note that there are multiple reports of spam of this kind, as well as people reporting having their wallets stolen. As for the leaks classification, these were websites that had links to download company leaks.

Before closing the technical analysis section, we’d like to note that monitoring the fast-flux network via passive DNS helps identify threats early and consequently blocks them. Since we’re dealing with a network made of compromised residential machines, simply blocking the IPs is not enough, as the IPs rotate often, but by knowing the nameservers and IPs that belong to the network, one can actively monitor DNS to identify new domains.

An example we’ve come across relates to the previously mentioned phishing campaign against Arculus. This campaign is still ongoing, and on February 5th, 2025, we identified a domain (arculusdefi[.]at) that was registered on February 3rd, 2025, demonstrating that by monitoring the network, one can proactively detect new domains.

Fast flux in the darkweb

Understanding the ecosystem that supports malicious activities provides key insights into the operations and relationships between actors. In this section, we’ll contextualize the reader on the offering of fast flux services in the darkweb, providing chronological insights on the availability of these services, with a focus on more recent activity.

To better understand what we should search for, it’s worth noting that fast flux services are mainly associated with bulletproof hosting (BPH) solutions. These services advertise themselves as being resistant to takedown requests, and also to allow almost any kind of usage. On top of that, they also provide good anonymity to their clients, reflected by exclusively accepting cryptocurrencies, advertising that no logs are kept, and even only having instant messaging as a way to buy the product.

Historical overview

We tried to determine the prevalence of fast flux being sold on the dark web by searching forums for the keywords `fastflux` and `fast flux`, in hopes of arriving at services being sold that have fast flux capabilities.

In Fig. 6 we present the number of posts per year from 2007 to 2024. Throughout these 18 years, there were nearly 1200 posts that reference fast flux, with three-quarters of the posts concentrated from 2021 onwards.

Even though the upward trend is only visible from 2018 onwards, the first mention of a BPH service with fast flux dates back to February 2008.

Recent activity

Knowing that the initial advertising of fast flux services dates back at least to 2008 gives us a sense of how established this technique is, but to understand if it’s still relevant, we’ll now focus on the last year of mentions of fast flux on the dark web.

We’re able to identify multiple services selling fast flux services, some were easily accessible on the web, while others were only accessible via direct messaging, which falls inline with the concerns of privacy and anonymity. We’re also able to observe that some services date back to 2013, while others are as recent as 2024.

We identified 4 easily accessible services:

- Dedione (dedione[.]store) - available since 2021

- Anonrdp (anonrdp[.]com) - available since 2023

- Centinelhost (centinelhost[.]com) - available since 2024

- Darksecure (darksecure[.]in) - available since 2024

Other services were also available but were only accessible by contacting the user directly. We do not have much information about these services other than their prices varying from 200 to 700 USD per month.

Conclusion

We’ve presented how we came across a fast-flux service and started collecting data about it to get a better understanding of how it was structured. We observed that the infrastructure is concentrated in a small number of countries and that the entities associated with it are residential IPs.

We’ve connected this service to a known botnet named Dark Cloud/Sandiflux by pivoting from a TLS certificate and noted that even though the service is not new, there are still multiple groups using it as C2, droppers, or to simply host carding websites.

By looking at both the historical and recent activity of BPH advertising on the darkweb, we note how an old technique is still being sold by multiple actors, which would indicate there’s still a decent market for such services. The relevance of fast flux today is further backed by the fact that these services are actively used by ransomware groups.

IoCs

List with IoCs can be found in the following link: https://github.com/bitsight-research/threat_research/blob/main/sandiflux/sandiflux_iocs.txt