It’s 2 AM. Do You Know Which AIs Your MCP Server Is Talking To?

Tags:

When Anthropic dropped the Model Context Protocol (MCP) in late 2024, it felt like the missing puzzle piece for AI tooling: a standard way for Large Language Models (LLMs) to talk to data sources, APIs, and pretty much anything else you can think of. Think of it as a USB-C port for AI, as the protocol’s creators like to say.

But like most shiny new standards, the devil’s in the details. Especially in those lines of documentation everyone tends to overlook in their rush to just get things working (been there, no judgment!). And when those details involve “optional authorization,” things can get interesting fast. That little caveat might be leaving thousands of MCP servers wide open to anyone who knows where to look.

This is the story of how we went hunting for exposed MCP servers on the internet and found hundreds that will not only tell a stranger exactly what tools and data they’re wired into, but will also cheerfully answer any question you throw at them. And when those strangers have malicious intent and know exactly what to do once they find these servers, the consequences can get very serious as we’ll see in a moment.

Note: For the sake of simplicity, when we talk about “exposed MCP servers,” we’re referring to servers that are not only accessible over the internet but also lack any form of authorization.

Disclaimer: Don’t get us wrong: MCP is awesome. It’s a powerful protocol that’s already reshaping how AI applications connect with external data sources and tools. Our goal here is simply to raise awareness within the community about something fundamental to maintaining MCP servers. So fundamental that it comes well before the flashier AI-era threats like prompt injection or anything in the OWASP Top 10 for LLM Applications.

Inside MCP: From message flow to real-world magic

Introduced in late 2024, MCP has rapidly emerged as a significant development in the AI ecosystem. Its promise of a standardized connection method for LLMs with tools, APIs and databases has generated considerable discussion.

The official definition outlines MCP as follows:

MCP (Model Context Protocol) is an open-source standard for connecting AI applications to external systems.

Using MCP, AI applications like Claude or ChatGPT can connect to data sources (e.g. local files, databases), tools (e.g. search engines, calculators) and workflows (e.g. specialized prompts)—enabling them to access key information and perform tasks.

Think of MCP like a USB-C port for AI applications. Just as USB-C provides a standardized way to connect electronic devices, MCP provides a standardized way to connect AI applications to external systems.

In other words, MCP introduces a standardized interface that abstracts away the complexity of individual data sources. Instead of every AI application needing to implement custom logic for each new database, API, or knowledge repository, they only need to understand how to communicate through MCP.

Some foundational MCP concepts

Before we move on, let’s break down a few key components of the MCP protocol.

The main actors: MCP Host, MCP Client, and MCP Server

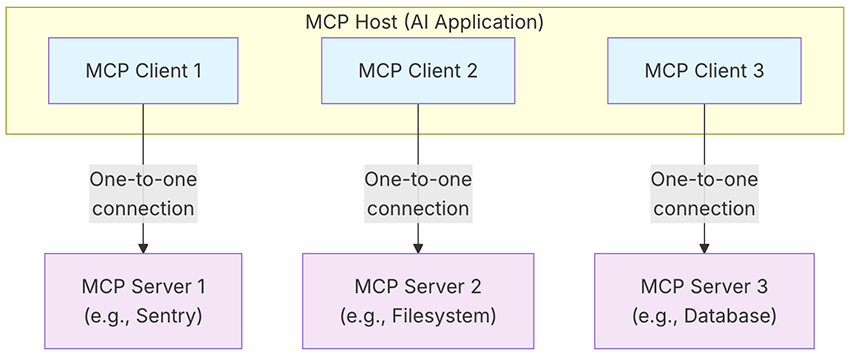

The MCP Host is the AI application or runtime environment where AI-driven tasks are executed. It also serves as the operator of the MCP Client, which acts as an intermediary between the host and one or more MCP Servers.

These servers allow the client to access external services and perform tasks, exposing three key primitives: tools, resources, and prompts. Here, we’ll focus on tools, which are the executable functions an AI application can call to actually do things, like running a file operation, making an API call, or querying a database. If you’d like to explore resources, prompts, or any other part of the MCP protocol, we highly recommend checking out the official MCP documentation. We promise it won’t be boring. We’ve been there and genuinely enjoyed it!

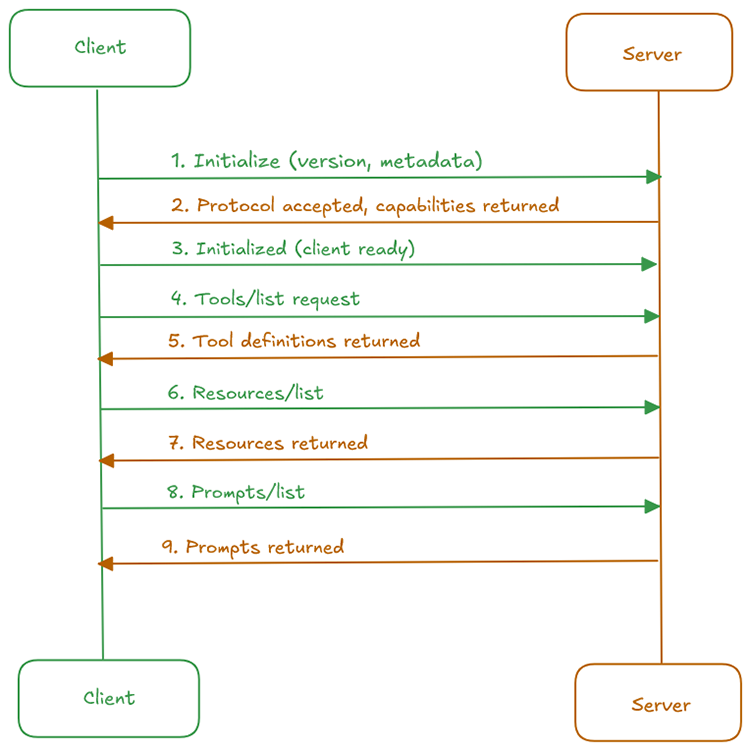

The protocol handshake

A crucial first step in establishing an MCP client-server connection is the handshake. During this process, the client and server negotiate a compatible protocol version to ensure smooth communication. Once the connection is initialized, the client can request a list of tools, resources, and prompts from the server and then repeatedly invoke them at will. The following diagram illustrates this communication flow:

How MCP clients and servers talk to each other

The MCP specification defines the protocol’s data layer and outlines how MCP clients and servers communicate using the JSON-RPC 2.0 standard. It further describes the transport layer and the mechanisms for message exchange between the two parties:

Stdio

This method uses standard input (stdin) and standard output (stdout) streams for direct communication between local processes on the same machine. All communication between MCP clients and servers happens locally.

Streamable HTTP

This transport type enables remote communication between the MCP clients and servers using the HTTP POST method for client-to-server messages, with an optional Server-Sent Events (SSE) endpoint for streaming capabilities. In this setup, the MCP client sends requests via HTTP POST, and the server can respond with either a single JSON message or a continuous stream of messages delivered over time through SSE.

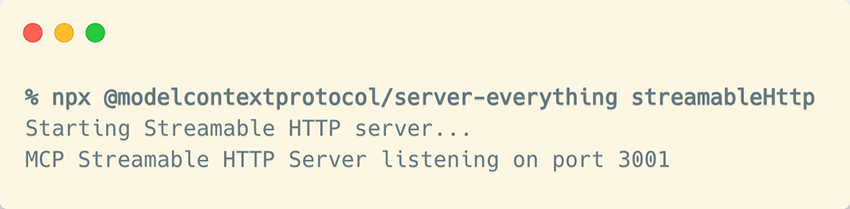

You can try this yourself to see it in action. For simplicity, we’ll use a dummy MCP server for demonstration purposes: The Everything MCP Server1.

It can be spun up easily with a single npx command:

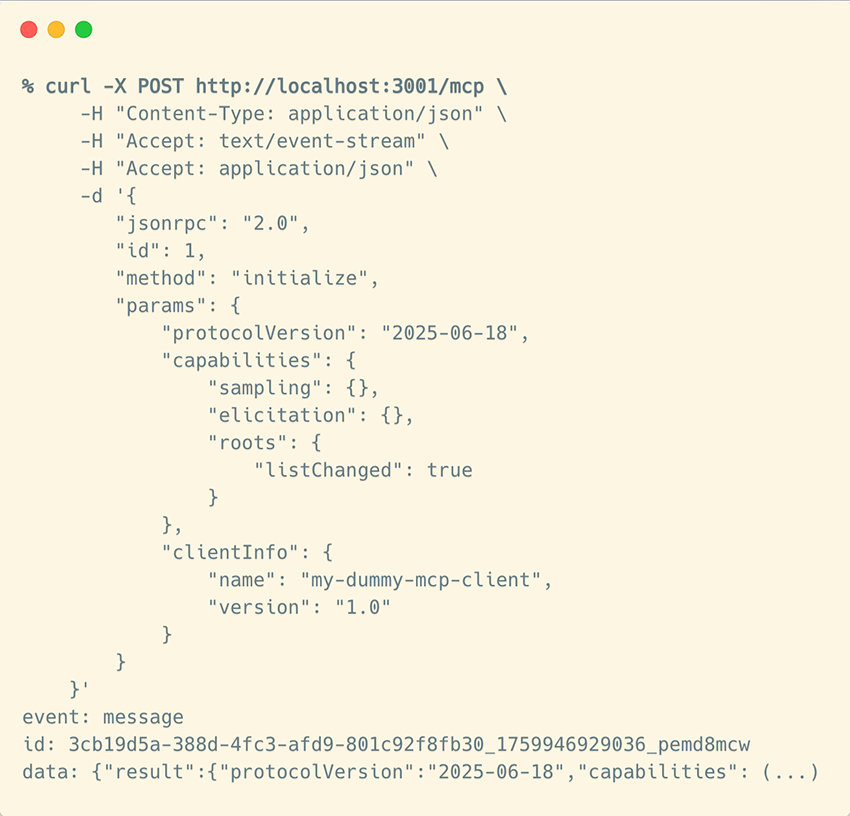

You’ll now have the /mcp endpoint ready to receive POST requests. You can use curl to send the initialize message, which is the first message in the MCP handshake we saw earlier:

initialize message to our demo MCP server using StreamableHTTP as transport type(Legacy) HTTP with SSE

The initial MCP specification introduced HTTP with SSE as a transport type. It relied on two separate HTTP connections: one for Server-Sent Events (server-to-client messages) and another standard POST endpoint for client-to-server communication. This approach is now deprecated, with Streamable HTTP being the preferred option for new implementations when the MCP server is remotely accessible and stdio cannot be used.

We can use the same dummy MCP server as before to see how these two separate HTTP connections work together. We’ll start by spinning up the Everything MCP Server in SSE mode:

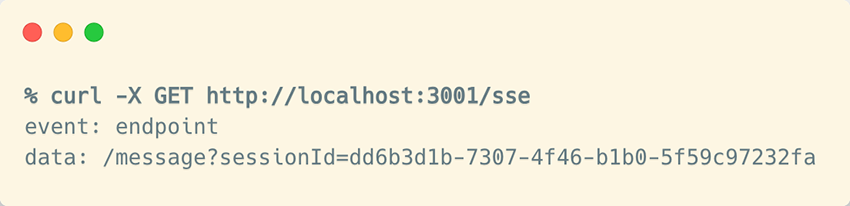

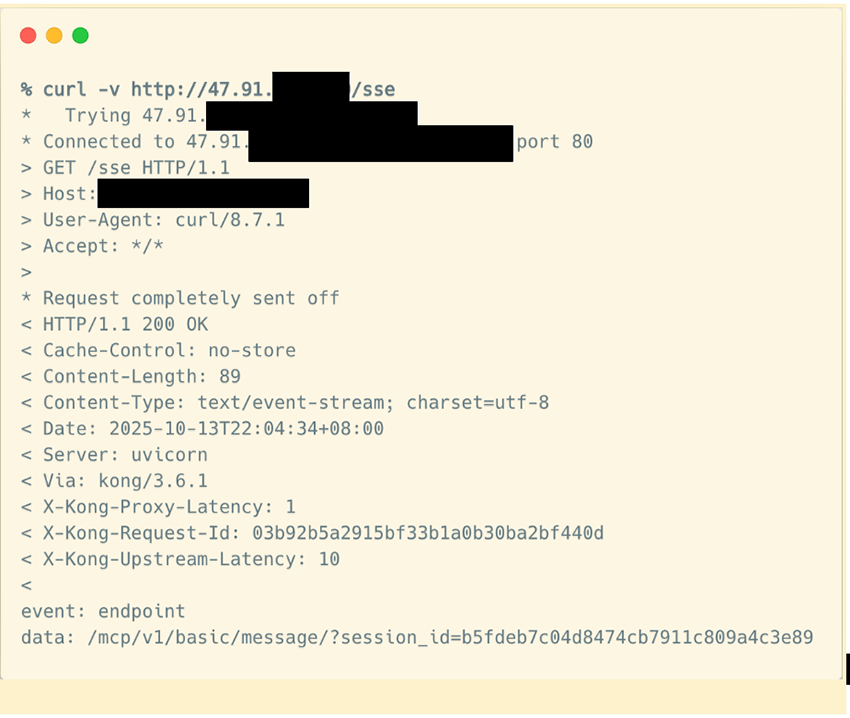

Here, unlike what we saw earlier, we first need to send a GET request to the /sse endpoint to obtain the session URL:

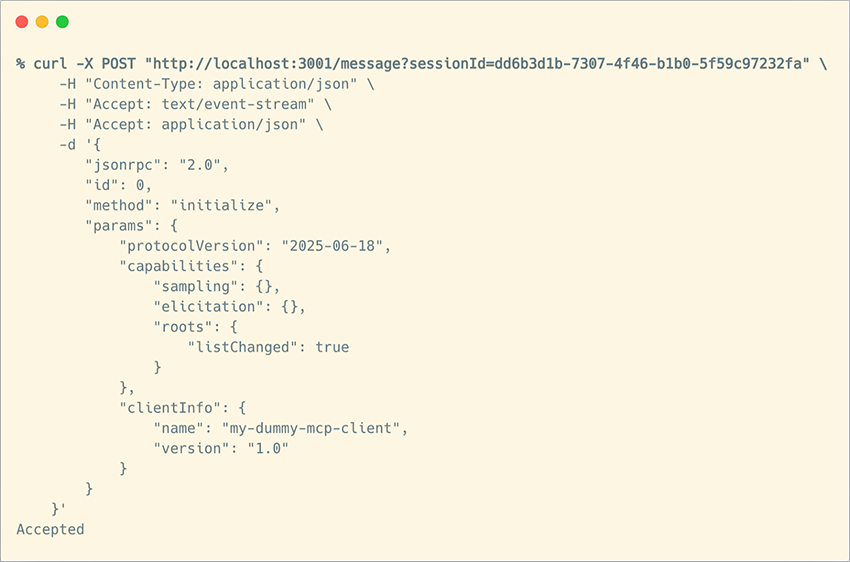

You’ll notice that your curl command hangs. That’s because this isn’t a regular HTTP endpoint, but an SSE endpoint that stays open, waiting for more events to arrive. Now, the same initialize message we saw earlier should be sent to the endpoint you just received. When you do that, you’ll see the response is simply an HTTP 202 Accepted with no payload returned:

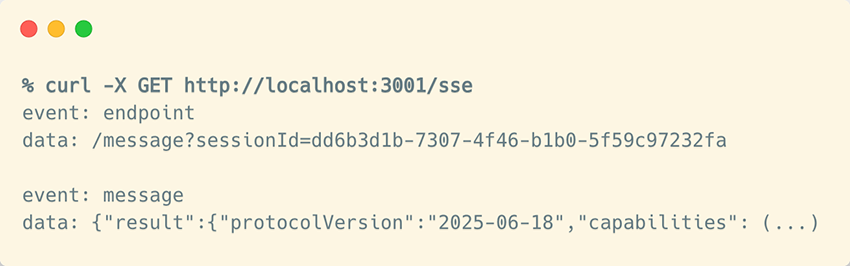

initialize message through the current session URLThe actual data from the server is delivered through the SSE connection that was opened earlier:

initialize message on the previously opened SSE event streamHow does that work in real life?

We know, we know. You’re absolutely right. That was pretty low-level, and most users don’t really care about those details. But we thought it’d be cool to take a peek under the hood and see what’s actually happening when you use MCP.

Of course, there are several SDKs you can use right out of the box to handle all that communication for you. And if you prefer, or if you’re not on the developer side of things, you can use any existing LLM-based application that already supports MCP.

Here in this demo, we’ll use Gemini CLI as our MCP host/client and DBHub as our MCP server. DBHub calls itself a “universal database MCP server connecting to MySQL, PostgreSQL, SQL Server, MariaDB” so it’s a great way to show how MCP lets an AI application talk directly to a database.

We’ll start by firing up the DBHub MCP server with the --demo flag (“The demo mode includes a bundled SQLite sample "employee" database with tables for employees, departments, salaries, and more”). We’ll also use the --transport flag to expose it over Streamable HTTP:

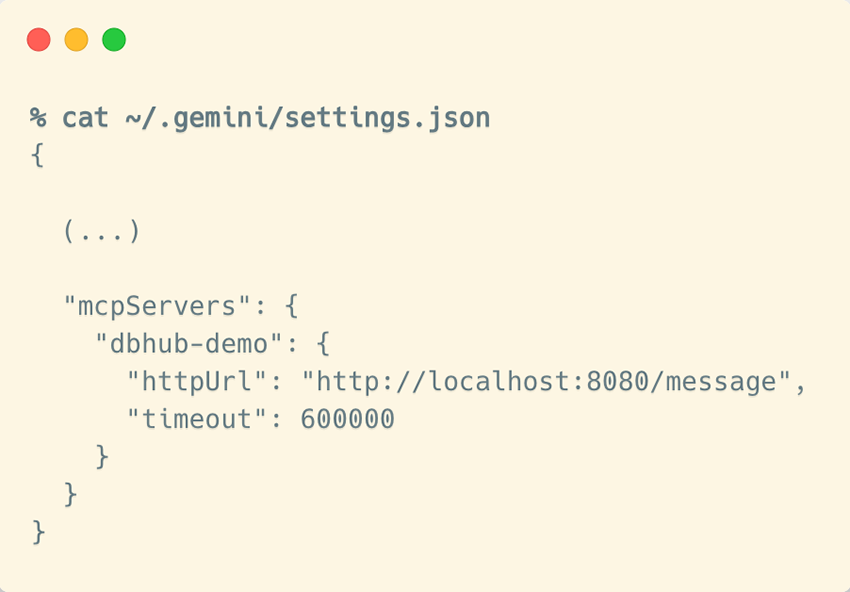

Now all it takes is configuring the Gemini CLI to point to our MCP server and that’s it!

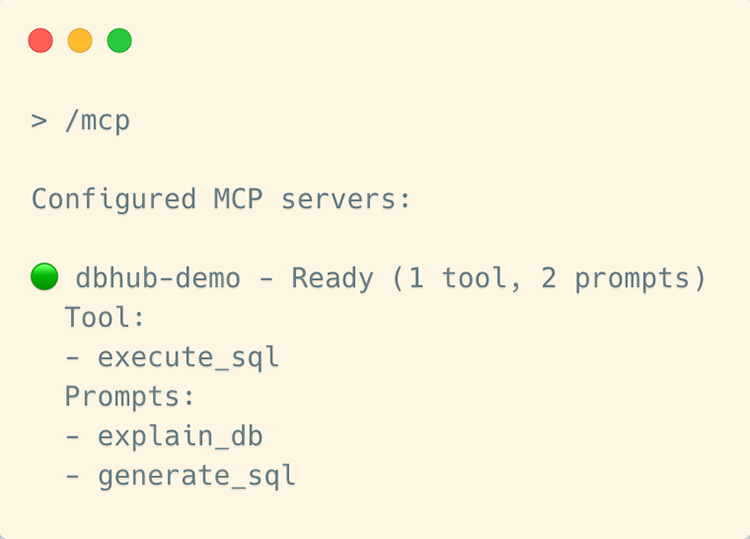

If you now run /mcp in your Gemini CLI, you’ll see that one MCP server is connected, exposing both tools and prompts. As mentioned earlier, this means the MCP host (in this case, Gemini CLI) has handled all the heavy lifting performing the full MCP handshake and message exchange between the client and server so you don’t have to. Now you’re all set to start asking your database questions in plain natural language!

Let’s poke around to see which tables we can access, and then dump one to take a closer look.

(and notice there’s no mention of our MCP server in the prompt because there’s no need to)

employees table for usThat’s it? Really?

Yep, that’s really it! Our AI app is now hooked up to the MCP server at http://localhost:8080/message, ready to use the tools it advertised during the handshake we explored earlier. Why do you ask? Do you think something’s missing?

Ah, yeah…glad you asked! (And if you didn’t, just pretend you did). So, we’ve exposed our demo MCP server over an HTTP endpoint that could be accessed remotely by multiple clients (even though our demo was running locally). The catch? We haven’t added any authorization mechanism. That sounds… well, a little dangerous, to say the least.

By now, we’re hoping we’ve earned your attention for the rest of the blog post.

According to the MCP specification…

Let’s see what the latest MCP specification has to say about authorization:

Authorization is OPTIONAL for MCP implementations. (...) Implementations using an HTTP-based transport SHOULD conform to this specification

Okay, so that’s the point: the MCP specification doesn’t enforce the use of authorization mechanisms for accessing MCP servers. It simply recommends that implementers follow the spec’s guidance (which happens to be OAuth 2.1), but ultimately, it’s up to each MCP server’s owner to decide whether (and how) to implement authorization. And many simply don’t.

The most important message of this post

This optional authorization mechanism left up to you as the MCP server owner is exactly what we wanted to highlight. MCP is still such a new technology, and everyone’s in a rush to test it, play with it, and roll it out across their organization. But that rush to get something working in production can have disastrous consequences. Especially if a developer (like the one we were pretending to be in our demo earlier) overlooks this crucial detail, or if a vibe coder building their next $1B startup sees their AI-powered app “just working” with an MCP server that happens to be wide open to the world, completely unaware that their coding assistant just exposed it to the internet.

While Anthropic authored the MCP specification, it’s not their job to enforce how every server handles authorization. The specification offers guidance, not guarantees. So if you’re planning to implement an MCP server within your organization, whether you’re building one from scratch or using an existing one (and there are plenty out there!), keep in mind that:

- Because authorization is optional, it’s easy to skip it when moving from a demo to a real-world deployment, potentially exposing sensitive tools or data.

- Many MCP servers are designed for local use, but once one is exposed over HTTP, the attack surface expands dramatically. That’s when “optional” authorization becomes a real liability. The trusted boundary you assumed no longer applies.

Hopefully, by now, it’s clear that exposing an MCP server to the internet without any kind of authorization in front of it is basically an open invitation for malicious actors to use it as a proxy to reach whatever data or services its tools expose.

Imagine you’ve carefully configured your database, filesystem, API service or any other resource you’ve connected as a tool to your MCP server, following every security best practice you can think of. You’re confident that only your MCP server can access those data sources, and you settle in for a peaceful night’s sleep. But if that MCP server is exposed to the internet, anyone can use it to pivot into the very services you thought were protected. Malicious possibilities are endless:

- If you’re exposing databases or filesystems, that information could be easily exfiltrated (just like we did in our earlier demo) or even modified, if write access is allowed

- If your tools use third-party APIs to access other services, anyone exploiting your exposed MCP server could gain the same access and privileges

- If it’s a paid API service, a malicious actor could use your exposed MCP server (and your valuable API key) for free, and you’d be the one footing the bill.

- If someone simply wants to cause chaos, they could trigger a denial-of-service attack by issuing millions of requests through your MCP server, exhausting resources until the provider blocks your API key entirely.

There’s so much that could go wrong that we could spend all day listing scenarios, but you probably get the point by now. And the point is this: if you’re experimenting with MCP servers or thinking about hosting your own, it’s easy to get caught up in the buzz around new AI attack vectors like prompt injection and other trendy exploits and, in the process of trying to defend against them all, you simply forget the basics. So, don’t expose your MCP server to the internet unless you have a really good reason to. And if you do, make sure it’s protected by a proper authorization mechanism.

But if you’re the kind of person who needs to see it to believe it, stick with us, because we went hunting for exposed MCP servers with no authorization in place, and what we found was pretty alarming. We promise, the examples ahead will get your attention.

Our hunting for exposed MCP servers

The detection payload

In theory, this should be straightforward and no different from detecting any other service in the wild. We just need to send a payload to a given target and analyze the response. If it matches the expected pattern, it’s bull’s-eye.

We’ve already dissected the MCP protocol, so it should come as no surprise what our detection payload will be. Of course, it’s the initialize message. And since we also know exactly what a valid response looks like, if we receive that back, we can be 100% sure we’ve found an exposed MCP server that happily initialized a connection from a client without even checking for authorization.

Our |

The expected response is structured similarly to this |

Where should we look for exposed MCP servers?

Now it’s time to define our target scope. Here’s what we know, which will help narrow down our scan:

- We cannot detect MCP servers that use the Stdio transport type, since they are not remotely accessible

- MCP servers accessible via Streamable HTTP or HTTP with SSE are inherently HTTP endpoints

So far, so good. We’ve already outlined the data we need to send as our detection payload, and we know it must be sent to HTTP-based endpoints. However, in practice, there are a few challenges to consider when aiming for scalable detection.

Testing all HTTP-based endpoints isn’t practical

Bitsight Groma, our internet scanning engine, identifies millions of unique HTTP-based endpoints across the internet. The current total is on the order of hundreds of millions, so while we could test them all, it would take a considerable amount of time.

To make this search efficient, we need to build a focused list of endpoint candidates that are more likely to host an MCP server. This way, we only test a small fraction of all HTTP-based endpoints, turning it into a much more targeted scan.

We spent a good amount of time investigating the most common characteristics of MCP servers, both with and without authorization mechanisms in place. At a high level, these are some of the most promising signals that can guide us to focus on certain HTTP-based endpoints when looking for exposed MCP servers while safely ignoring others:

“MCP-like” hostnames

This one is pretty obvious. If you look at the current landscape, you’ll notice that many companies are offering remotely accessible MCP servers to their customers, so they don’t have to maintain them on the client side. Here are a few random examples:

- “Stripe hosts a Streamable HTTP MCP server that’s available at https://mcp.stripe.com“ (source)

- “Other programs (...) can connect manually using Notion MCP's public URL (https://mcp.notion.com/mcp) as a custom connection” (source)

- “Connects directly to Figma’s hosted endpoint at https://mcp.figma.com/mcp” (source)

- “PayPal built an MCP server that lets merchants use natural language with their favorite MCP clients (...) In a production environment for a live site, replace the sandbox URL with this URL: https://mcp.paypal.com/sse” (source)

There’s a pattern, isn’t there? It seems that the mcp subdomain within a Fully Qualified Domain Name (FQDN) is a strong indicator that it’s probably hosting an MCP server. Fortunately for us at Bitsight, it’s fairly easy to gather a large number of hostnames with mcp as a subdomain, since we actively collect millions of publicly resolvable domains for various purposes, with large-scale hostname-based scanning being one of them.

Clues in HTTP headers

Those that live in the shadows and are rarely seen by end users, the HTTP headers sometimes leak important bits of information. In this case, we can take a look at a few of them, including (but not limited to):

Content-Typeheader: A pretty obvious place to look. As we’ve learned, MCP works either with raw JSON or embedded in an HTTP stream, soapplication/jsonandtext/event-streamare good hints to look for in this headerServer header: Although it can be easily redacted or modified, this header is still a useful place to look for hints when the original value is exposed. Assuming (and we think it’s a safe assumption) that most MCP servers rely on Anthropic’s official SDKs and implementation guidelines, we can start inferring which web servers are most likely in use when someone builds an MCP server with the Python, TypeScript, Go, or any other existing SDK- Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) headers: We’ve also noticed that some

Access-Control-*headers can sometimes expose information commonly associated with MCP servers

Low-hanging fruits in MCP endpoint discovery

As we’ve already seen, MCP endpoints are typically found at /mcp or /sse, following the conventions defined in the specification. However, as with any other convention, nothing prevents someone from hosting their MCP server /in/a/deeply/nested/URL/path: the classic “security through obscurity” move. So we also need to narrow down the URLs to be tested.

For this research, we limited ourselves to the standard ones (/mcp and /sse) and also tested the root (/), since there’s a good chance those would be the juiciest and yield the most results.

Fast-forward to the scan results

Ok, so we built our list of potential candidate URLs that might be exposing an MCP server. We ended up with a set of targets showing one or more of the signals we defined as indicators of an MCP server, and we tested all of them across the three standard paths: /mcp, /sse, and /.

Sure, we hit a few false positives along the way, but we eventually filtered those out. For the remaining targets, we built a quick-and-dirty tool to perform the full MCP handshake and collect all the data we wanted from each exposed MCP server: most importantly, the list of tools, but we also gathered the list of resources, prompts, and some extra metadata from the initialize response.

On a personal note, it was a fun ride, but we’ll spare you the boring details and get you straight to the results.

And the number of exposed MCP servers we found is…

Roughly 1,000 exposed MCP servers with no authorization in place, from which we were able to retrieve all their available tools.

At first glance, it might not seem like an impressive number, right? But think about it: we’re talking about a technology that was announced to the public barely a year ago, and we’re already seeing hundreds of instances missing any form of authorization. That suggests things could get worse over time, which is why we hope this blogpost helps raise awareness before it does.

It’s also important to consider another angle. The MCP servers we found are the ones exposed on the public internet, but there could be many more running inside internal networks or application backends under the same conditions, and their owners might not even realize it. Just because they’re only accessible internally doesn’t mean they’re harmless. An exposed MCP server within a corporate environment could still be exploited by a malicious insider or through lateral movement during a breach.

Some alarming examples showing why this is really bad

Surely you’re curious about what kinds of exposed MCP servers we found out there and what they could let a malicious actor do. So were we. That’s why we analyzed many of them, reviewing the tools we were allowed to list and inferring what could be done if we were actually malicious adversaries.

While it’s true that some MCP servers are open and free to use for legitimate reasons (for example, we found a few that simply let AI applications access public documentation for a given service or product), many others were far more concerning. Here are just a few examples of the tools implemented by those exposed MCP servers (really, just a few; we found way too many!):

An exposed MCP server that would allow management of a Kubernetes cluster and its pods:

{

"name": "pods_delete",

"description": "Delete a Kubernetes Pod in the current or provided namespace with the provided name"

}, {

"name": "pods_exec",

"description": "Execute a command in a Kubernetes Pod in the current or provided namespace with the provided name and command"

}, {

"name": "pods_get",

"description": "Get a Kubernetes Pod in the current or provided namespace with the provided name"

}, {

"name": "pods_list",

"description": "List all the Kubernetes pods in the current cluster from all namespaces"

}, {

"name": "pods_list_in_namespace",

"description": "List all the Kubernetes pods in the specified namespace in the current cluster"

}, {

"name": "pods_log",

"description": "Get the logs of a Kubernetes Pod in the current or provided namespace with the provided name"

}, {

"name": "pods_run",

"description": "Run a Kubernetes Pod in the current or provided namespace with the provided container image and optional name"

}

Another one would allow access to a Customer Relationship Management (CRM) tool:

{

"name": "list_accounts",

"description": "Retrieve all available accounts from EspoCRM"

}, {

"name": "list_users",

"description": "Retrieve all available users from EspoCRM"

}, {

"name": "list_teams",

"description": "Retrieve all available teams from EspoCRM"

},

Another one that could be used to send WhatsApp messages, perfect for spam!

{

"name": "send_whatsapp",

"description": "Send a WhatsApp message to a single number"

}, {

"name": "bulk_send_whatsapp",

"description": "Send WhatsApp messages to multiple numbers"

}, {

"name": "get_session_status",

"description": "Check the status of a WhatsApp session"

}, {

"name": "validate_number",

"description": "Check if a number is valid on WhatsApp"

}

The holy grail: Remote Code Execution as an available tool through an MCP server!

{

"name": "execute_shell_command",

"description": "Execute shell commands through the proxy server"

},

{

"name": "broadcast_websocket",

"description": "Broadcast message to all WebSocket clients"

},

{

"name": "get_server_status",

"description": "Get current server status and statistics"

}

(Bonus) MCP honeypots?

Just FYI, this was something we found rather curious. Although we didn’t dig too deeply into it, our scan uncovered what appear to be hundreds of honeypots mimicking MCP servers that use HTTP with SSE as their transport type. We found more than 1,100 cases where a GET /sse request returned the following:

We sampled a few of them and confirmed the following:

- The

session_idparameter was exactly the same across all of them - When we tried to access the endpoint URL to initialize the MCP connection, no valid data was returned

- All of them had hundreds of open ports, likely to mimic different network protocols

- They occasionally returned random HTML pages when accessing

/sseor other paths

So, there’s little doubt they’re honeypots ready to catch someone (like us) scanning for MCP servers on the internet.

We just want to raise awareness (our call to action)

We can’t stress this enough: see this blog post as a call to action to raise awareness about an emerging problem. MCP was announced roughly a year ago, and we’re already seeing a surprising number of MCP servers in the wild with no authorization mechanisms in place, effectively inviting any malicious actor to use them however they want. This could be the first symptom of something much more widespread in the near future. As adoption grows, we can expect to see even more exposed MCP servers appear online.

If you plan to leverage MCP in your organization, that’s great! MCP is here to stay and as we’ve seen, it’s an excellent way to connect AI applications to external tools and datasets. But please, do it securely:

- Don’t expose your MCP servers to the internet unless you absolutely need to. For instance, if you’re using them to power internal AI applications, keep your MCP servers restricted to internal networks. Even better, consider using the Stdio transport type: running locally means one less remote attack vector

- Even if you use remote transport types like Streamable HTTP for your internal MCP servers, and especially if you need to make them publicly accessible so your customers can use them in their applications and services, follow the specification’s best practices. The official recommendation is to use OAuth 2.1, though other secure alternatives may fit your use case.

1 “This MCP server attempts to exercise all the features of the MCP protocol. It is not intended to be a useful server, but rather a test server for builders of MCP clients. It implements prompts, tools, resources, sampling, and more to showcase MCP capabilities.”