Continuous Monitoring: 3 Keys to Government Success

In recent years, the US government has become a leading advocate for continuous monitoring of security threats and vulnerabilities. But how effectively are departments and agencies in implementing these programs? And how do we measure success?

Moving Towards Continuous Monitoring

Though it’s become a popular concept, continuous monitoring wasn’t always in vogue. When the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) was enacted in 2002, the law required agencies to document security practices, including taking inventory of information systems and writing security plans. External firms would audit the plans and grade departments and agencies based on their efforts.

This approach earned two main critiques. First, though agencies may have had well documented security programs, they weren’t necessarily implementing those programs effectively. In fact, during the mid-2000s, security experts showed that agencies could achieve good grades in these audits but still be the victims of significant data breaches. Second, the focus on documentation usually meant that agencies were spending more time writing their policies than implementing the actual security controls.

In recent years, Congress expressed bipartisan, bicameral disapproval of the way that government was approaching cybersecurity. In 2009, Senator Tom Carper of Delaware said, “Too often we have agencies who manage what we call paper compliance rather than really addressing the security of their networks. We want to go beyond paper compliance.” Congressmen Darrell Issa and Elijah Cummings echoed this sentiment, stating, “A check-the-box mentality will never be a match for the creativity of a hacker attempting to fly under the radar and access that agency’s secrets.”

In 2014, after years of oversight and investigation, a new FISMA law was enacted. This law shifts the focus of agencies away from policy-based reporting to reporting of specific threat, incident, and compliance information. The new law also seeks to eliminate inefficient or wasteful reporting requirements that would allow federal agencies to allocate more resources for protection, rather than paperwork.

Last month, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued an annual report to Congress describing agency efforts in implementing FISMA. The report reveals that continuous monitoring systems are being widely adopted throughout the government: 19 agencies now have programs in place. This is a big step in the right direction; however, there are three key areas for improvement.

Keys to Future Success

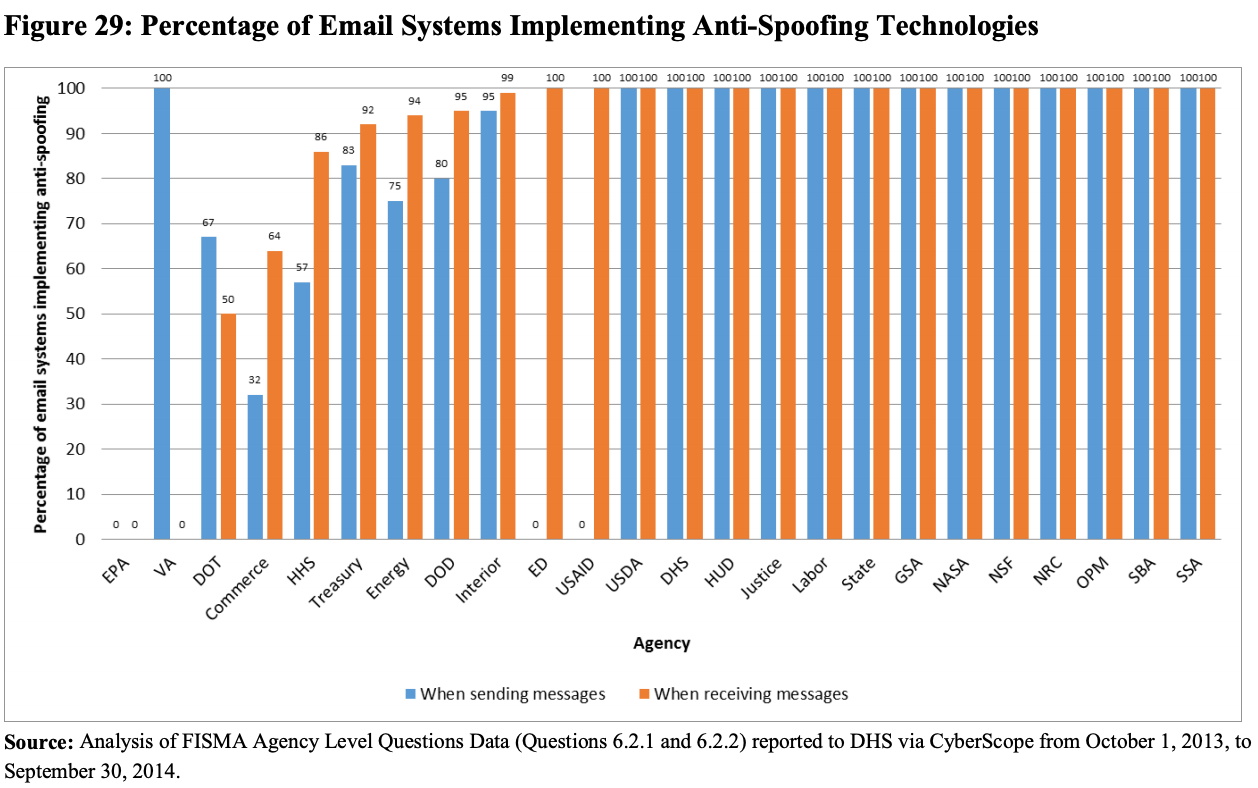

First, to truly evaluate continuous monitoring programs, the OMB must move towards automated reporting of agency data. For instance, the OMB asked departments about the percentage of email systems with anti-spoofing technologies when sending and receiving messages. Several departments, as shown in the figure below from the OMB’s annual report on FISMA, stated that they are implementing anti-spoofing technologies on 100% of inbound and outbound traffic during FY 2014:

Bitsight, a security ratings company, measures the effectiveness of the implementation of this control via our SPF and DKIM grades. According to our records, several departments have poor grades -- in the C-F range -- indicating that the control is either ineffective, or, in the case of an “F”, not implemented at all.

Second, quantifiable metrics are needed to measure the effectiveness of continuous monitoring programs. The OMB reported that on average, 92% of government assets are under continuous monitoring programs. While this is an impressive number, it doesn’t tell us much about the effectiveness of continuous monitoring in reducing threats and vulnerabilities to government networks.

For starters, measuring the average amount of time taken to resolve security incidents would provide valuable insight into these programs. In February, the Obama administration listed breach detection and incident response time as one of its five priorities for cybersecurity. Future OMB reports should incorporate these and other “timeliness” metrics in order to truly evaluate the effectiveness of a continuous monitoring program. In order to report these metrics, departments and agencies need to adopt continuous performance monitoring that will allow them to measure and benchmark their effectiveness in key areas.

Lastly, the current definition of “continuous monitoring” in FISMA is limited to departments and agencies and does not include third parties. As we learned in the cyber attack against Target, third party vendors can pose significant risk to organizational security. The government’s continuous monitoring metrics for FISMA include “automated asset, configuration, and vulnerability management... of the assets connected to the organization.” But tens of thousands of third parties hold sensitive data or perform services on behalf of the government. Establishing continuous assessment of critical vendors is an important initiative for the government to get a better handle on its own data risk.

Thanks to tremendous leadership from the executive and legislative branches, FISMA has progressed significantly from a “check-the-box” exercise. While more work is left to fully implement continuous monitoring solutions, the eventual outcome will be a more secure, resilient federal cyber ecosystem.