Ransomware, breach sharing, stealer logs, credentials, and cards. What has shifted and how to respond.

Stating the Obvious: Vulns On the Rise in 2025

Tags:

Happy New Year! As we usher in a year with some pleasant mathematical properties, I wanted to take a brief look back at one of the stories that was most interesting to me as a security data nerd from last year: our dependency on the National Institute of Standards and Technologies’s (NIST) National Vulnerability Database(NVD), and what the degradation in service has meant to the flow of information about new CVEs.

TL:DR

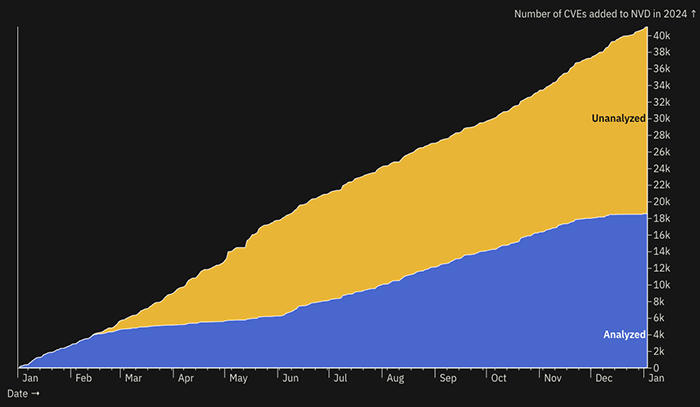

- NVD stumbled in 2024, and despite trying to recover, it still hasn’t analyzed about half of the vulnerabilities published in 2024.

- They have their work cut out for them; 2025 will likely see upwards of 50k vulnerabilities published, bringing the total to well over 300k

- Prioritization will be the key component of vulnerability management, and threat intelligence should be a major part of that.

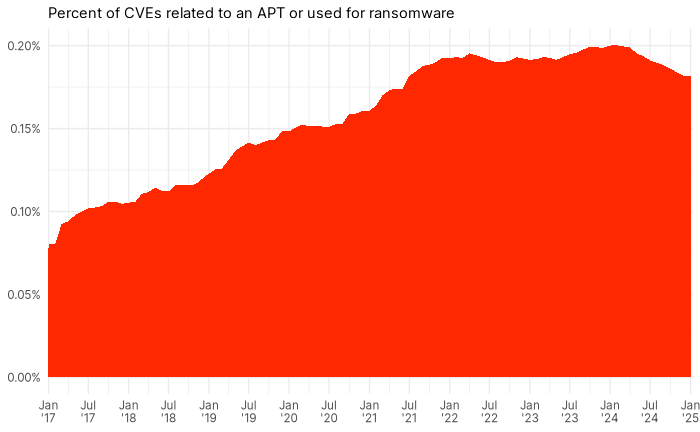

- Only ~0.2% of published vulnerabilities are used in ransomware attacks or by APTs.

- But 24.2% of organizations were exposed to this small number of vulns in 2024.

NVD, CVEs, and the lack of info

Let’s start with a quick recap. The NVD is a NIST-run database that uses a number of different vulnerability frameworks to disseminate information about new vulnerabilities. In particular, when a new vulnerability is published (this in itself is a complex process), then NVD takes a look at the vulnerability and uses CVSS to score it, CWE to identify the root software flaw, and CPE to identify which vendors and products the CVE affects. Moreover, they have a handy dandy API that allows folks to access that information in a nice programmatic way.

The trouble came in February of 2024 when NVD stopped doing their NVD thing and many organizations were left wondering “Where am I going to get CVE information now?” Being the thought leader I am, I wrote up a nice post about where else CVE information can be found (particularly the originating Certified Numbering Authorities CNAs). However, being a federated process, the information out of CNAs is less than consistent.

In my June post, I examined how different CNAs approach the CVE process differently. I elaborated on that work at the Vuln4Cast Technical Colloquium, and wanted to share an update on some of the results in that talk. In particular, I elaborated on the expanding number of CNAs joining in the CNA process, evaluated them on what CVE information they were actually providing, and noted that they all utilize various CVE adjacent frameworks in different ways. You can check out the entirety of the presentation here.

I won’t go over every single result in that presentation here. My marketing department is already exasperated with me for handing them a near 40 page report that is coming out soon.1 However, since the new year is time for predictions, that work gives us some good framing for the new year. So let’s look back and think ahead. First, note that NVD has not caught up with their evaluation process, and given their current rate, are unlikely to anytime in 2025 unless a significant change takes place. Of the more than 40k CVEs published in 2024, just shy of 18.5k.

Predicting 2025 CVEs

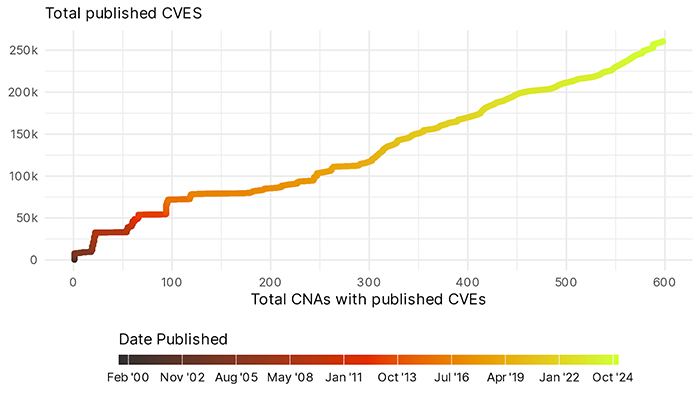

As noted in the “5 for 2025” post, I expect the number of CVEs to grow. This will be primarily driven by the increase in the number of CNAs as the process of becoming a CNA has become more transparent and easy2. There is good correlation between the number of CVEs published and CNAs publishing them.

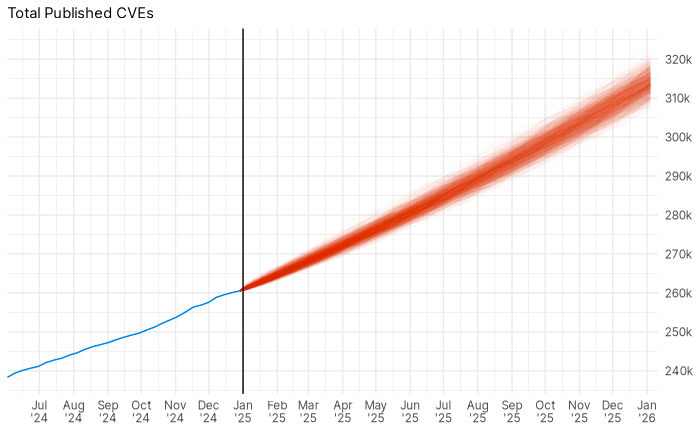

So let’s ask two questions: how many CVEs are there going to be in 2025, and how much of a threat will they pose? First a raw bold prediction: With 95% certainty there will be between 48,675 and 58,956 new CVEs published in 2025. That will almost certainly bring the total CVEs above 300k sometime in the late summer or autumn.

How’d I get here? Only nerds who care about math can find out in the footnote at the end of this sentence.3 Am I overestimating? Underestimating? Maybe! Who knows, maybe at the end of 2025 everyone will come back to this post to mock me.

New CVEs and the threat they pose

OK the next question: “how much of a threat are they going to be”? There are multiple definitions for “bad”:

- Widely distributed

- Hard to fix

- Presence in critical infrastructure

- Easy Exploited by attackers

- Consequences of attack

Let’s explore those last two a bit ,shall we? In case you hadn’t heard the good news, Bitsight recently acquired Cybersixgill, a threat intelligence company. Among the many interesting datasets they bring to table, one includes information on which CVEs are utilized by APTs and which are used in ransomware attacks. In the deluge of CVEs predicted for 2025, it’s going to be more important than ever to just focus on ones that pose an immediate threat to an organization, rather than wasting time on stuff that attackers aren’t wasting their time on. Ransomware or APT associated vulns seem “real bad” to me.

So how many are there? If we combine the C6G data with some data from CISAs KEV catalogue, we can see the total percent of “real bad” vulns.

Two things are interesting about Figure 3, first there has been growth in the percentage of CVEs since 2017, but that has plateaued in the last three years. While comforting at first blush, remember we are seeing an exponential growth in CVEs. A fixed percentage of an exponentially growing quantity is… well, exponential.

Still at this point 0.2% is eminently manageable for most organizations. However, even though it’s a manageable number of vulnerabilities, those vulnerabilities are pretty common. If we look at what Bitsight can observe in 2024, 24.2% of organizations were vulnerable to a CVE known to be used in ransomware or by an APT. Everyone needs to do the right little bit of work to make themselves safer from these big threats.

What’s it mean for you?

Cybersecurity is hard, especially when resources are limited, and the number of threats facing an organization are myriad. Each threat has its own unique profile, and one that likely changes from organization to organization. In the new year and foreseeable future, it will be critical for organizations to prioritize defenses against their most pressing threats. That will mean not only knowing what assets your company has out on the Internet (a Bitsight speciality) and how they might be exposed or already compromised (our bread and butter), but also who various ne’er do wells are targeting. Throughout this new year the fine folks at Bitsight TRACE will keep you abreast of how and where these threats are evolving, so you can act accordingly.

1Don’t worry I cut it down to be more digestible.

2Perhaps too easy? The Linux kernel became a CNA in February and quickly began publishing at a rapid rate. In 2024 they published 4325 CVEs, ranking 3rd among CNAs after MITRE and Patchstack.

3 I fit a model of weekly published CVEs using a non-linear double exponential growth model, log(CVEs published in a week) = a +ebt + ct, where t is the time and a, b, and c are model parameters to be fit. Why the sort of strange double exponential? A single exponential also fit, but had a significantly lower AIC. Same with an exponential growth plus linear trend model. Moreover the residuals of the model failed to reject the null of the Anderson-Darling test that they were normally distributed. Once we have an idea of the total number of CVEs that are going to be published in a week, we can run a Monte-Carlo simulation to better understand what totals for the year are going to look like.

One last caveat is that this model will be wrong in the long run. It may be exponentially growing, but given that we live in a finite universe, it’s unlikely to continue growing exponentially forever. Indeed, every logistic curve looks like an exponential far from its carrying capacity. And it will be wrong when the CVE process inevitably changes again.