Unpacking Colibri Loader: A Russian APT linked Campaign

Tags:

Between July and October 2022 Bitsight observed a ColibriLoader malware campaign being distributed by PrivateLoader, which was identified as being utilized by the threat actor UAC-0113, a group linked to Sandworm by CERT-UA. Sandworm is known to be a Russian advanced persistent threat (APT) group affiliated with The Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (GRU). In this research, we present how to manually “unpack” a sample from a recent campaign. Unpacking means reaching the final stage of the malware, which contains its main functionality. We also share some threat-hunting signatures and indicators of compromise which can be utilized in defense and tracking efforts.

About Colibri

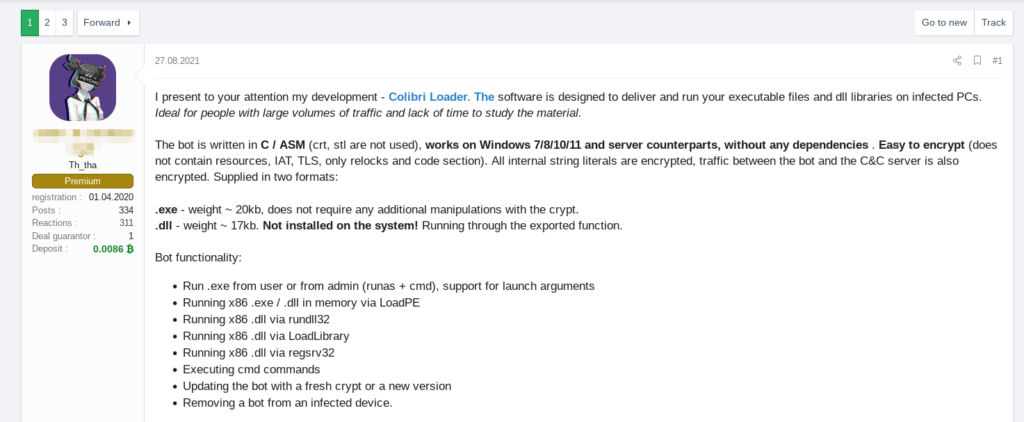

ColibriLoader is a Malware-as-a-Service family, first advertised on XSS.is cybercrime forum in August 2021 to "people who have large volumes of traffic and lack of time to work out the material" (Fig. 1). For $150/week or $400/month, it offers a small, unpacked, obfuscated loader written in C and assembly, along with a control panel written in PHP. As its name suggests, it’s meant to deliver and manage payloads onto infected computers. Moreover, the malware ignores systems from Commonwealth of Independent States countries (Armenian, Azerbaijani, Belarusian, Hungarian, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Romanian, Russian, Tajik, Turkmen, Uzbek).

Fig. 1 - Post on XSS.is cybercrime forum by user “c0d3r_0f_shr0d13ng3r”

PrivateLoader distributing Packed Colibri

PrivateLoader is a loader from a pay-per-install malware distribution service that has been utilized to distribute info stealers, banking trojans, loaders, spambots, rats, miners and ransomware on Windows machines. While monitoring PrivateLoader malware distribution activity, we spotted ColibriLoader being distributed between July and October. Many security products automatically classified these samples and we noticed that all of them have the tag “Build1”, which may represent the botnet or campaign id. Contradicting the author's advertisements, we noticed some indicators suggesting that the samples are packed, such as their size, which should be around 20KB, and the fact that it contains only two sections, the .text and .reloc, which was not the case.

In order to evade antivirus security products and frustrate malware reverse engineering, malware operators leverage encryption and compression via executable packing to protect their malicious code. Malware packers are software programs that either encrypt or compress the original binary, making it unreadable until it’s placed in memory. In general, malware packers consist of two components, a packed buffer, the actual malicious code, and an unpacking stub responsible for unpacking and executing the packed buffer. Threat Actors make use of packers when distributing their malware as they remain an effective way to evade detection and make the malware harder to analyze. Manual analysis can defeat these protections and help develop tools that aid in this costly task.

Unpacking ColibriLoader

Let’s have a look at a sample dropped by PrivateLoader on September 4, 2022. First, we tried to use unpac.me service to try to unpack it automatically but we were unlucky. So, let’s dive deep into this sample.

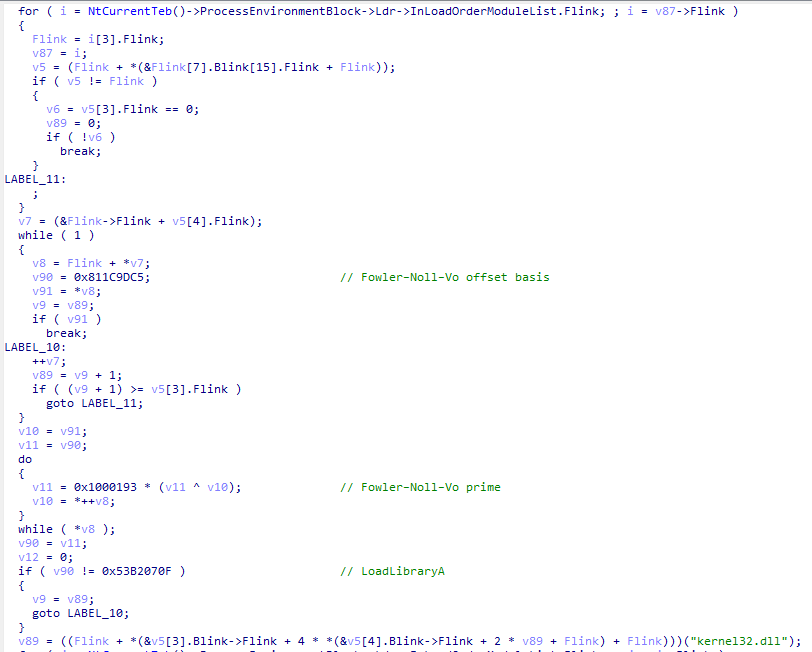

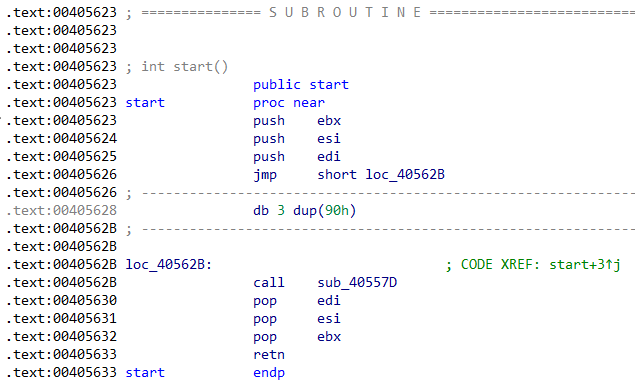

Resolving the Windows API

Opening it on IDA Pro, on the main function (Fig. 3), we can see a pattern that seems to be a way of dynamically resolving some Windows API functions, which are usually crucial to understand the code behavior quickly. The malware walks the process environment block (PEB), looking for the in-memory loaded modules base addresses on the current process, finds the functions exported by each, hashes them, and compares it with the hash of LoadLibrary. Then, it calls LoadLibraryA to load kernel32.dll to get a module handle for it, but does not actually load it since it is already loaded by default, and then searches for the target export function (a more detailed explanation can be found here). By searching on Google for the constants in the code that generates the hash, we confirmed the hashing algorithm in use is Fowler–Noll–Vo.

Fig. 3 - Example of Windows API resolution.

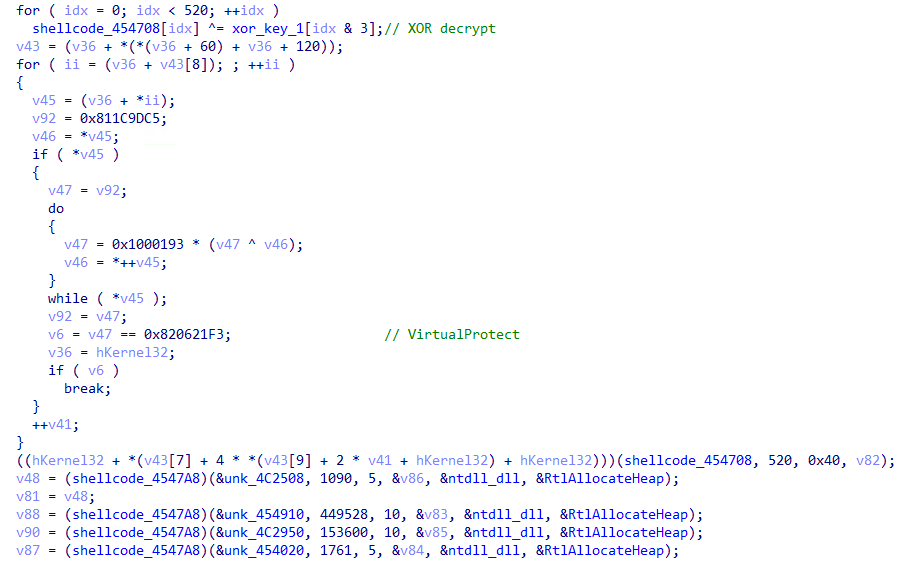

Encrypted Shellcode and Executable

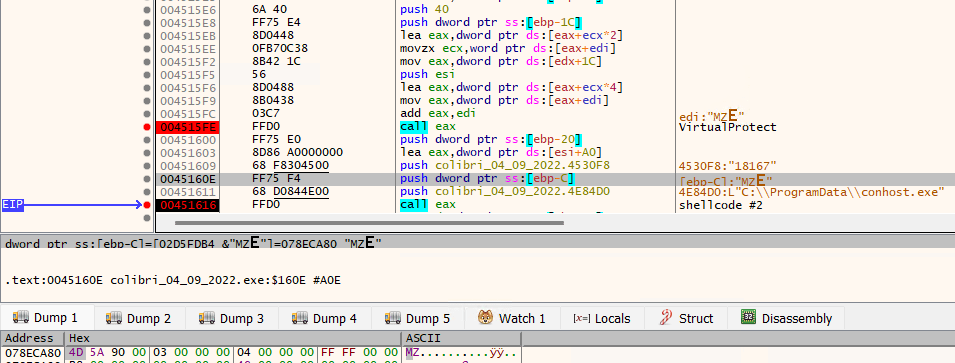

Looking a bit further through the code, we can spot what seems to be an XOR decryption of 520 bytes of shellcode at 0x454708, where the key is “2760”, and also the change in the protection of that region (VirtualProtect) to PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE (0x40), as well as four calls of a function within that region (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 - Shellcode decryption.

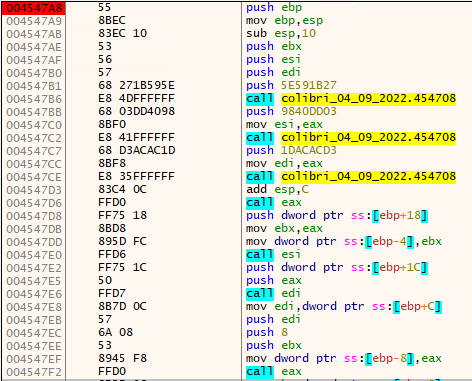

We can confirm it by disassembling the shellcode function at 0x4547A8 after running it on x32dbg (Fig. 5)

Fig. 5 - Decrypted shellcode #1 function at 0x4547A8.

This function allocates memory on the heap and copies some data to it. The size of the region to be allocated is on the second argument. Going back to the main code, there’s XOR decryption done on each piece of data, and subsequently a call to VirtualProtect to enable execution of the newly decrypted shellcode (Fig. 6). Their arguments are what seems to be a file path, a pointer to an executable, what seems to be an XOR key, and probably the size of the executable (0x12C00 bytes, or 76.8KB)

Fig. 6 - Decrypted executable at 0x78ECA80.

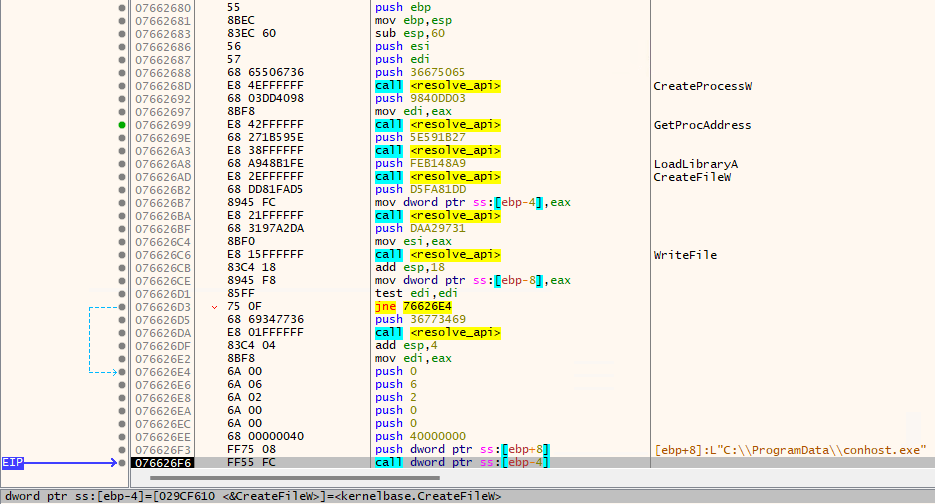

After saving to file that executable and sending it to VirusTotal, we can see that it was already uploaded. Again, no luck on unpacking it with unpac.me. Entering the last decrypted shellcode, it seems to dynamically resolve some Windows API functions by passing a hash and then it creates a file at C:\ProgramData\conhost.exe (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 - Decrypted shellcode #2.

After running it, a file was indeed dropped at the expected location, which turns out to be the same file we manually dumped. VirusTotal shows 173 executables dropping this file, most with compilation and first-seen timestamps from September 2022.

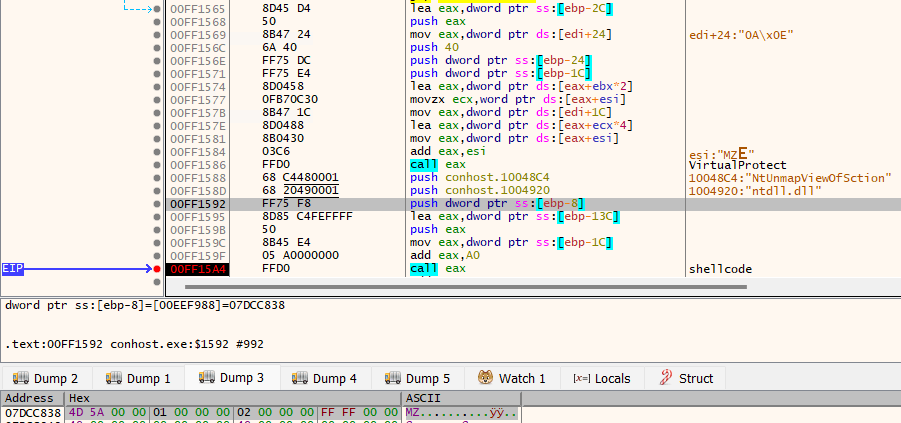

Let's have a look at the dropped file. Opening again on IDA Pro, looking at the main function, it seems very similar to the previous stage, almost a copy, with some minor changes. In the end, we can quickly spot the same pattern of resolving VirtualProtect, calling it, and then calling the decrypted shellcode, just as seen before. After running on x32dbg with a breakpoint at that last call, we can see as before that the pointer to the newly decrypted executable is the second argument (Fig. 8). However, this time the size is not being passed as an argument, but we can get it from other places, such as the call to a function that decrypts the executable, where the size to be decrypted is passed on the first argument.

Fig. 8 - Decrypted executable at 0x7DCC838.

Going back, by putting a breakpoint on the call to decrypt the executable, we can see that the size is 0x5000 bytes (or 20KB). We can now extract the executable from memory and have a look at it. The file seems to be a valid executable with only two sections, .text and .reloc. There’s sufficient evidence to conclude that we have successfully unpacked the ColibriLoader.

At the time of this research, this last stage was not yet on VirusTotal. Later, we found a quicker way of unpacking the malware. We used this script to extract executables from memory dumps (from a sandbox run for example) and then the YARA rule we share below was used to find the Colibri sample.

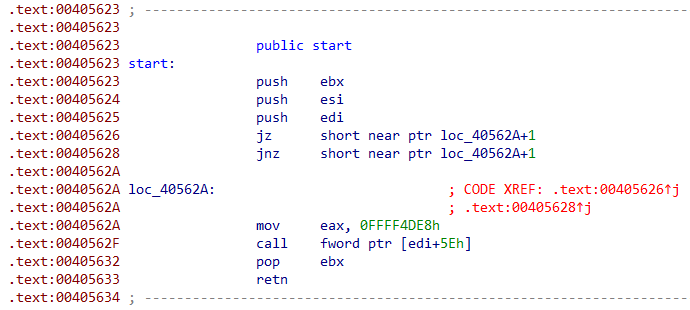

Deobfuscating ColibriLoader

Finally, let’s have a very quick look at the actual malware. The first anti-analysis trick we encounter is called opaque predicates (Fig. 9); It’s a commonly used technique in program obfuscation, intended to add complexity to the control flow. There are many patterns of this technique but in this case, the malware author simply takes an absolute jump (JMP) and transforms it into two conditional jumps, jump if zero (JZ) and jump if not zero (JNZ). Depending on the value of the Zero flag (ZF), the execution will follow the first or second branch. However, disassemblers are tricked into thinking that there is a fall-through branch if the second jump is not taken (which is impossible as one of them must be taken) and try to disassemble the unreachable instructions (often invalid) resulting in garbage code.

Fig. 9 - Example of ColibriLoader opaque predicates anti-analysis technique.

In order for IDA Pro to load it properly, we need to patch the first conditional jump to an absolute jump and NOP out the second jump (Fig. 10). We’ve automated this task using myrtus0x0’s code since SmokeLoader also uses this technique.

Fig. 10 - Patched ColibriLoader.

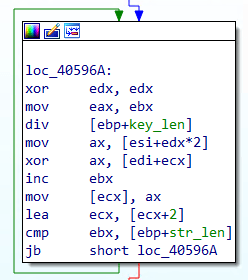

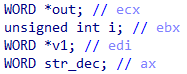

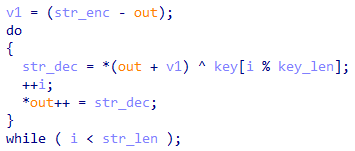

The last analysis we did was trying to extract the strings the malware uses, which will contain indicators of compromise, such as command and control servers. After looking a bit through the code, it wasn’t hard to find the string decryption function at 0x40594B since there are 71 cross-references for it, so it’s probably the most used function (Fig. 11 and 12).

Fig. 11 - Example call to the string decryption function.

|

|

This code seems straightforward enough. Strings are encrypted with an XOR key passed as an argument to the function. Yet, we didn’t need to script this out because we’ve found a working IDA script from Casperinous. Here are the results:

0x401faf %s\\%s

0x401fd4 \\Microsoft\\WindowsApps

0x401ffa Get-Variable.exe

0x402020 powershell.exe -windowstyle hidden

0x402046 %s:Zone.Identifier

0x40229c %s\\%s

0x4022c1 \\WindowsPowerShell

0x4022e7 dllhost.exe

0x40230d %s:Zone.Identifier

0x402579 %s\\%s

0x40259e \\Microsoft\\WindowsApps

0x4025c4 Get-Variable.exe

0x402706 %s\\%s

0x40272b \\WindowsPowerShell

0x402751 dllhost.exe

0x4028e5 %s:Zone.Identifier

0x402999 runas

0x4029bf cmd.exe

0x4029e5 /c %s%s%s %s

0x402b49 %s\\rundll32.exe %s,%s

0x402c4e %s /s

0x402c74 runas

0x402ca8 %s\\System32\\regsrv32.exe

0x402cff %s\\SysWOW64\\regsrv32.exe

0x402e48 /c %s%s%s %s

0x402e6e cmd.exe

0x402e94 open

0x403041 %s%s

0x403612 6rmUi1hRdfbV0QyXqAoT

0x4037c0 /c chcp 65001 && ping 127.0.0.1 && DEL /F /S /Q /A %s%s%s

0x4037e5 cmd.exe

0x4038db Software\\Microsoft\\Windows NT\\CurrentVersion

0x403903 ProductName

0x4039cc Unknown

0x403c07 %08lX%04lX%lu

0x403c81 /create /tn COMSurrogate /st 00:00 /du 9999:59 /sc once /ri 1 /f /tr

0x403ca7 %s\\schtasks.exe

0x403e4b %s\\schtasks.exe

0x403e71 /delete /tn COMSurrogate /f

0x404058 Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

0x404488 zpltcmgodhvvedxtfcygvbgjkvgvcguygytfigj.cc

0x4044ad yugyuvyugguitgyuigtfyutdtoghghbbgyv.cx

0x404582 /gate.php

0x4045a8 hf9qkeO66MP7WJXkg9rp

0x4045ce 2OrnJZG6Wtbzd4bKJoS0

0x4045f4 %s?type=%s&uid=%s

0x40461a check

0x404640 GET

0x404666 HTTP/1.1

0x40489d 1.2.0

0x4048c3 Build1

0x4048e9 /gate.php

0x40490f hf9qkeO66MP7WJXkg9rp

0x404934 2OrnJZG6Wtbzd4bKJoS0

0x40495a %s?type=%s&uid=%s

0x404980 update

0x4049a6 POST

0x4049cc HTTP/1.1

0x4049f2 %s|%s|%s|%s|%s|%s|%s

0x404a18 32bit

0x404a3e 64bit

0x404d9c Build1

0x404dc3 /gate.php

0x404dec hf9qkeO66MP7WJXkg9rp

0x404e13 2OrnJZG6Wtbzd4bKJoS0

0x404e3a %s?type=%s&uid=%s

0x404e61 ping

0x404e88 POST

0x404eaf HTTP/1.1

0x404ed6 %s|%s|%s|%s|%s|%s|%s

0x4054d3 0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

These decrypted strings also allow us to further reverse the malware more quickly if we need to.

Wrap-up

We presented a way to manually unpack the ColibriLoader samples from a campaign linked to the threat actor UAC-0113. Later, we found a quicker way of unpacking the malware using the pe_extract.py script combined with a YARA rule which detects unpacked samples of ColibriLoader, which we share below. All indicators of compromise and threat-hunting rules can be found at https://github.com/bitsight-research/threat_research

Threat Hunting Signatures

Here’s a YARA rule to detect packed ColibriLoader samples based on a typo:

The following YARA rule detects unpacked ColibriLoader samples based on the string decryption function. This rule was tested on VirusTotal and it returned few results with first-seen timestamps between September 2021 and November 2022.

Here’s a Suricata rule to detect the ColibriLoader network traffic, specifically its C2 check-in request, tested with a PCAP generated from a sandbox run of the malware:

Indicators of Compromise

Unpacked ColibriLoader sample - 59f5e517dc05a83d35f11c6682934497

173 Packed ColibriLoader samples:

https://github.com/bitsight-research/threat_research/blob/main/colibriloader/packed_colibri_samples.txt

More at https://github.com/bitsight-research/threat_research